#071: Flammulina velutipes, The Velvet Foot or Enoki

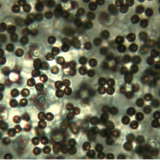

It’s often said that you can tell how edible a mushroom is by the number of names it has. This concept certainly applies to the edible Flammulina velutipes, which goes by the common names Enokitake (and the shortened form Enoki), Velvet Foot, Winter Mushroom, and Golden Mushroom, as well as many other derivatives and regional names (if you’re outside the United States, you probably call it something else!). Another reason the species has so many names is because it looks very different in the wild than it does in the grocery store: in the wild, it grows as an orange umbrella-shaped mushroom with a black fuzzy stipe, but when cultivated it grows as a pale thin needle-shaped (or perhaps spaghetti-shaped) mushroom with a tiny pileus. I generally use the names F. velutipes, Velvet Foot, and Enoki, since each one emphasizes a different physical aspect of the mushroom.

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)