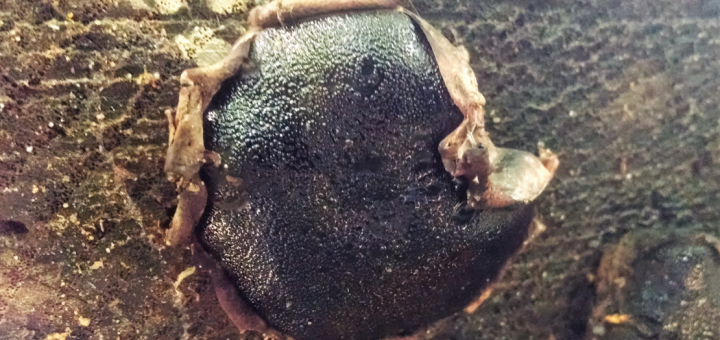

#019: Apiosporina morbosa, Black Knot

And now for something completely different: how to recognize different types of trees from quite a long way away.* Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) is the easiest tree in eastern North America to identify, thanks to the fungus Apiosporina morbosa, commonly known as Black Knot. Most Black Cherry trees are infected with A. morbosa, which causes dark swellings on branches and trunks. Older tree trunks are often marred by large swellings caused by A. morbosa that are up to twice the size of the trunk. These “knots” are easy to spot from a distance (especially in winter), so take advantage of this and amaze your friends by pointing out Black Cherry trees without relying on bark, leaves, or other details! On twigs and smaller branches, Black Knot makes the branches lumpy and thickened in places, looking remarkably like “dried cat poop on a stick” (thank Michael Kuo for that apt analogy).

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)