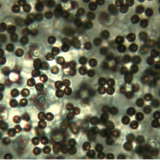

Lichens are composite organisms made up of two mutualistic, unrelated species: a photosynthetic organism and a fungus. I find that most people don’t really understand what lichens are, and that’s not surprising, considering the definition above. OK, so we’re all familiar with lichens: the green/grey/orange/brown crusts that form on sidewalks/trees/rocks/etc. But what, exactly, are they? Most people would probably classify them as plants or, more specifically, as mosses. This would seem reasonable, as they are often found growing alongside mosses and in other similar habitats. However, this is not the case at all. Lichens are actually composed of two or more separate species growing together as one organism. This unusual type of organism is known as a “composite organism.” Lichens always include one fungal partner (the mycobiont) and at least one photosynthetic partner (the photopiont). The photobiont can be a green alga (kingdom Plantae) or a cyanobacterium (a.k.a. blue-green alga,...

![#065: Trametes versicolor, the Turkey Tail [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-medium-empty.png)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)