#164: Histoplasmosis

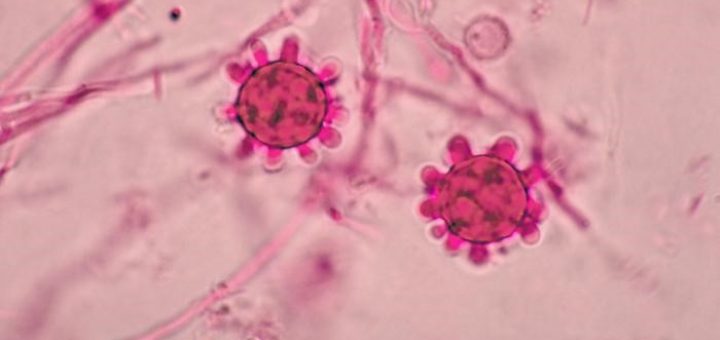

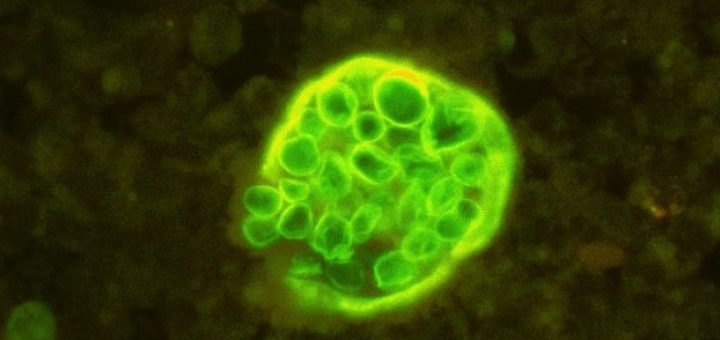

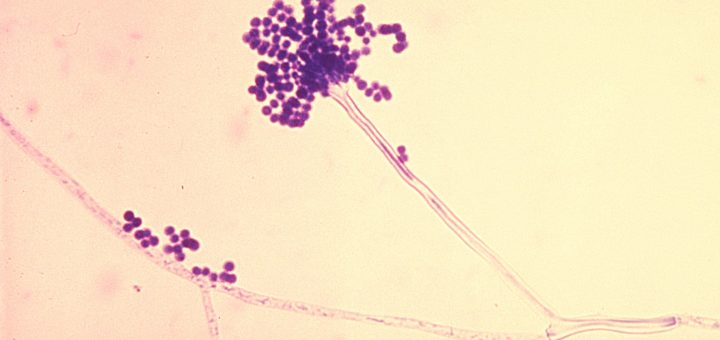

Histoplasmosis is a fungal disease caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. Like the other true human fungal pathogens, H. capsulatum lives as a mold in the environment but switches to an infective yeast form in the body. In nature, H. capsulatum grows on bird or bat droppings. This fungus is very common, especially in the Ohio and Mississippi River valley areas. However, H. capsulatum very rarely causes disease. As with most fungal diseases, people with a weakened immune system are most at risk of acquiring histoplasmosis.

![By walt sturgeon (Mycowalt) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Suillus-luteus-group-720x340.jpg)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)