#207: Ergot Alkaloids

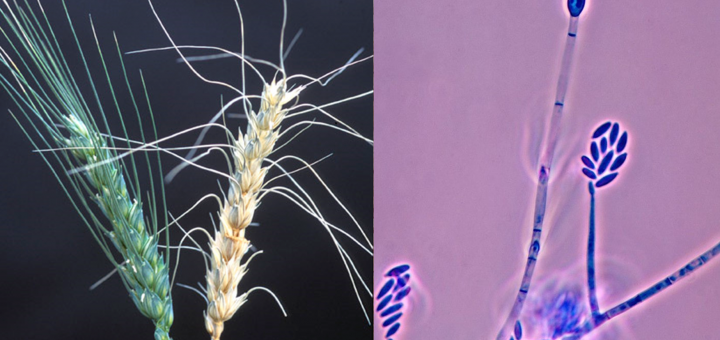

Ergot Alkaloids (EAs) belong to a large class of mycotoxins. They are primarily produced by fungi in the genera Claviceps and Epichloë, although Claviceps purpurea is responsible for most of the impacts on humans. EAs are most common in rye, but can be found in any cereal grain. The toxins were a significant problem in the middle ages, but modern agricultural techniques mean that exposure to enough EAs to cause symptoms is extremely rare.1,2 Sources Many fungi produce ergot alkaloids in many different plant hosts. Humans are impacted most by species of Claviceps, which infect seeds of grasses. The most problematic species is C. purpurea (see FFF#061), which infects rye. A variety of other species infect cereal grains but cause less contamination. Livestock can be sickened by infected grain or by ergot alkaloids produced by endophytes in pasture grasses, most notably by Epichloë coenophiala.1–3 This post focuses on Claviceps and...

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)