#164: Histoplasmosis

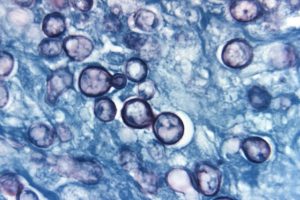

![Macroconidia of Histoplasma capsulatum. CDC/Dr. Libero Ajello [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Histoplasma-capsulatum-spores.jpg)

Macroconidia of Histoplasma capsulatum. Photo by CDC/Dr. Libero Ajello [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Pathogen Biology

H. capsulatum is a thermal dimorph, meaning it switches between growing as hyphae and as a yeast based on the external temperature. When the temperature is at or below 35°C, the fungus grows as hyphae. However, when H. capsulatum encounters temperatures at or above human body temperature (37°C), it grows as a yeast. When in yeast form, H. capsulatum divides through budding. In this process, a small outgrowth forms on a cell and slowly gets larger. When it is big enough, the yeast cell goes through mitosis and one of the daughter nuclei migrates into the outgrowth. The new cell then separates to become a new yeast cell. 1

The fungus normally survives in the environment as hyphae decomposing organic material. H. capsulatum grows particularly well in damp, acidic soil with a lot of available organic compounds. These conditions are often found in places with high concentrations of bird or bat droppings. Caves and chicken coops are excellent places to find the fungus. 3 Areas where birds nest in large groups in a small area are also likely to contain H. capsulatum. 1 The fungus can also inhabit decaying logs and damp riverbanks. Although the fungus grows on bird droppings, it cannot infect birds and birds therefore cannot bring the fungus to new areas. Bats, however, are susceptible to infection by H. capsulatum and can distribute the fungus in their droppings. 3

H. capsulatum produces three types of spores: macroconidia, microconidia, and ascospores. 1 The macroconidia are relatively large (8-14µm across), round, warty, single-celled, asexual spores that are produced on short protrusions from hyphae. Microconidia are also single-celled, asexual spores, but they are smaller (2-4µm across), round to pear-shaped, and are borne either on a short protrusion or directly on the hyphae. 4 The microconidia are important because they are the spore type that causes infection in humans. 5 Ascospores are sexual spores which in this case develop in a structure called a “gymnothecium.” 1 The gymnothecium is a roundish structure in which asci develop in a haphazard arrangement. 6 The hyphae surrounding the asci are loose, so the spores can easily fall out of the gymnothecium. H. capsulatum does not produce ascospores as often as the other spore types because ascospores are only formed when two sexually compatible hyphae from different individuals meet. 1

Distribution and Risk Factors

Bats, such as these Little Brown Bats, can transmit Histoplasma capsulatum in their guano. Photo by David A. Riggs [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The rates of infection are thought to be very high: in the year 2000, approximately 40 million Americans had had some form of histoplasmosis and about 200,000 new infections were estimated to occur per year. 1 This makes it the most common true fungal disease in the United States. 3 Fortunately, most people get a very mild form and may not even be aware of the infection. 1 Consequently, the number of people diagnosed with histoplasmosis is very low. Even in the most severe areas, the incidence of disease in people 65 years old or older is only 6.1 in 100,000. 8

People more at risk of contracting histoplasmosis are those with weakened immune systems and those venturing into areas contaminated with H. capsulatum. A weakened immune system is often the result of HIV/AIDS, medicine prescribed after an organ transplant, or other medicines such as corticosteroids. 8 Very young children who do not yet have a fully developed immune system are likewise at greater risk for histoplasmosis. 10 Exposure to a greater number of spores also increases the likelihood of infection. Activities such as construction, renovation, chicken farming, and caving are likely to disturb soil containing H. capsulatum spores. As a result, people who engage in or live near these activities have a higher risk of developing histoplasmosis. 3, 10

Symptoms

About 95% of people infected with H. capsulatum do not seek treatment and most do not experience any symptoms. 4, 11 People with a mild form of histoplasmosis can expect symptoms that could easily be mistaken for a cold or flu: fever, cough, fatigue, chills, headache, chest pain, and body aches. These symptoms appear 3-17 days after exposure to H. capsulatum spores and last up to a month. 11

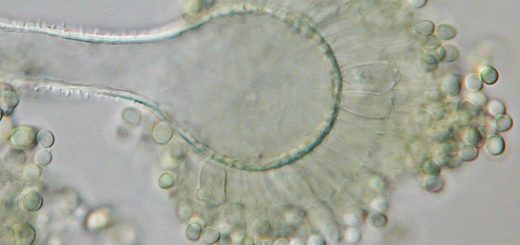

Budding yeast of Histoplasma capsulatum (infective stage). Photo by: CDC/Dr. Libero Ajello [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

H. capsulatum escapes the lungs by hitching a ride in a macrophage. Macrophages are supposed to eat and digest fungi, but the yeast form of the fungus is resistant to many of the macrophages’ digestive enzymes. Consequently, macrophages sometimes carry the yeast out of the lungs and into the lymphatic system. After the macrophage dies in a lymph node, the yeast is well placed to easily access the blood stream and move about the body. 3

In a small number of cases, histoplasmosis can later cause a disease called ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (OHS). This disease is not very well understood, even though it is a major cause of vision loss for Americans between the ages of 20 and 40. Although OHS has been linked to histoplasmosis, the exact mechanism that triggers OHS is unclear. The current theory suggests that H. capsulatum cells in the blood stream trigger OHS after become lodged in blood vessels around the retina. The immune system then removes the fungus, but some of the nearby tissues are mildly damaged. Occasionally, this damage will trigger OHS years or even decades after the initial infection. 12

In OHS, the blood vessels that supply the retina form abnormal growths of thin, fragile blood vessels underneath the retina. The growths cause problems by either triggering the formation of scar tissue or leaking excess fluid. Both processes prevent signals from the affected areas of the retina from being sent to the brain, thus causing partial blindness. The growths typically form near the center of the eye, which greatly disrupts vision but usually does not result in total blindness (peripheral vision is usually unimpaired). 12

Treatment

Most people do not need treatment for histoplasmosis, since it is mild and usually clears up fairly quickly. The antifungal drug itraconazole may be given orally to people whose symptoms last longer than a month. People with more severe infections are usually treated with amphotericin B (administered intravenously) followed by itraconazole (administered orally). 10 Depending upon the severity of the infection and the strength of the patient’s immune system, antifungal treatment can last anywhere from three months to one year. 5, 13

Ocular histoplasmosis syndrome is treated through photocoagulation. In this special type of laser surgery, lasers are used to destroy the aberrant blood vessels and part of the surrounding retina. Although this does result in the loss of some vision, it does prevent the malformed blood vessels from growing any larger. Clinical trials indicate that this reduces the amount of vision lost to OHS by over 50%. Unfortunately, OHS often recurs and further laser treatments may be required. 12

Taxonomy

There seems to be some confusion among mycologists over how to delineate the species of Histoplasma that cause histoplasmosis. Some consider H. capsulatum to have three varieties: H. capsulatum var. capsulatum, H. capsulatum var. duboisii, and H. capsulatum var. farciminosum. Other mycologists consider the differences between these groups significant enough to consider them separate species: H. capsulatum, H. duboisii, and H. farciminosum. 14, 15

The capsulatum type has a global distribution, so it infects more people than the others. The duboisii type is found only in sub-Saharan Africa, alongside the capsulatum type. Both of these types can infect humans. 4, 9 The farciminosum type is harmless to humans but can cause disease in horses. 4

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Phylum | Ascomycota |

| Subphylum | Pezizomycotina |

| Class | Eurotiomycetes |

| Subclass | Eurotiomycetidae |

| Order | Onygenales |

| Family | Ajellomycetaceae |

| Genus | Histoplasma |

| Species | H. capsulatum Darling16

H. capsulatum var. capsulatum Darling17 H. capsulatum var. duboisii (Vanbreus.) Cif. 18 H. capsulatum var. farciminosum (Rivolta) R.J. Weeks, A.A. Padhye & Ajello19 H. duboisii Vanbreus. 20 H. farciminosum (Rivolta) Redaelli & Cif. 21 |

See Further

http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/jan2000.html

http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/histoplasmosis/index.html

http://www.mycology.adelaide.edu.au/Fungal_Descriptions/Dimorphic_Pathogens/Histoplasma/

Citations

1. Thomas J. Volk. Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for January 2000. Tom Volk’s Fungi (2000). Available at: http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/jan2000.html. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

2. Histoplasmosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/histoplasmosis/index.html. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

3. Jazeela Fayyaz, Klaus-Dieter Lessnau, Ravikanth Vydyula & Maciej P. Walczyszyn. Histoplasmosis: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology. Medscape (2016). Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/299054-overview?pa=RTdhgcY0%2BAq48QlNI3eyAeo%2BV93kDB%2B%2FqoLi0KjU93Gy4hXz%2FlgK8RU7nKn6S8iRpuL1vVcWRf2Hueno2ieqeuN5lPYw%2FtQ7Z8WOOzpssmw%3D. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

4. David Ellis. Histoplasma capsulatum. Mycology Online (2016). Available at: http://www.mycology.adelaide.edu.au/Fungal_Descriptions/Dimorphic_Pathogens/Histoplasma/. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

5. Erika M. Young & Mitchell Goodman. Histoplasmosis and HIV Infection. HIV InSite (2006). Available at: http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=kb-00&doc=kb-05-02-06. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

6. Goldman, E. & Green, L. H. Practical Handbook of Microbiology, Third Edition. (CRC Press, 2015).

7. Sources of Histoplasmosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/histoplasmosis/causes.html. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

8. Histoplasmosis Statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/histoplasmosis/statistics.html. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

9. Antinori, S. Histoplasma capsulatum: More Widespread than Previously Thought. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 90, 982–983 (2014).

10. Sanjay G. Revankar & Jack D. Sobel. Histoplasmosis. Merck Manuals Consumer Version Available at: https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/infections/fungal-infections/histoplasmosis. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

11. Symptoms of Histoplasmosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/histoplasmosis/symptoms.html. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

12. Facts About Histoplasmosis. National Eye Institute (NEI) (2009). Available at: https://nei.nih.gov/health/histoplasmosis/histoplasmosis. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

13. Treatment for Histoplasmosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/histoplasmosis/treatment.html. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

14. Histoplasma. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?TableKey=14682616000000067&Rec=56704&Fields=All. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

15. Histoplasma capsulatum. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?TableKey=14682616000000067&Rec=29897&Fields=All. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

16. Index Fungorum – Names Record 102749. Index Fungorum Available at: http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/NamesRecord.asp?RecordID=102749. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

17. Index Fungorum – Names Record 417609. Index Fungorum Available at: http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/NamesRecord.asp?RecordID=417609. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

18. Index Fungorum – Names Record 353523. Index Fungorum Available at: http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/NamesRecord.asp?RecordID=353523. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

19. Index Fungorum – Names Record 131919. Index Fungorum Available at: http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/NamesRecord.asp?RecordID=131919. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

20. Index Fungorum – Names Record 298462. Index Fungorum Available at: http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/NamesRecord.asp?RecordID=298462. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

21. Index Fungorum – Names Record 252097. Index Fungorum Available at: http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/NamesRecord.asp?RecordID=252097. (Accessed: 28th October 2016)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)