#162: Candida albicans

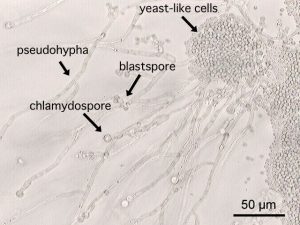

Candida albicans is unique among opportunistic pathogens because it produces both yeast and hyphae. By GrahamColm (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

Normal Life Cycle

About three quarters of the global population have C. albicans living in their bodies. Under normal conditions, the fungus inhabits the mucus membranes of the mouth, intestines, and genitals as a commensal organism.ii In this case, the body allows the fungus to exist and the fungus does not do any damage. Under normal conditions, C. albicans survives by breaking down sugars and other nutrients.iii

Most people get C. albicans from their mother when they are born and keep the fungus throughout their life. It is also possible to pick up the fungus later in life. In hospital settings, there is about a 40% chance that an uninfected patient will get the fungus from a hospital employee.iv

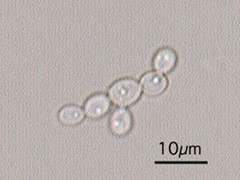

Candida albicans yeast cells. By Y tambe (Y tambe’s file) [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Truly pathogenic fungi use hyphae to invade tissues and yeast to travel through the blood stream.vii Consequently, the hyphal mode of growth is generally more virulent than the yeast mode.viii It is unclear whether C. albicans exists as a yeast or as hyphae while living as a commensal. It is possible that the commensal fungus uses both growth modes, but this is difficult to observe directly.ix

C. albicans uses only asexual methods of reproduction, but it has some limited mechanisms for genetic recombination. Although the fungus is diploid, it can fuse with a cell of the opposite mating type to create a tetraploid cell. This tetraploid cell then divides to create two diploid cells. During this division, some chromosomes can get lost and some genes can get swapped between chromosomes. Although these events are rare, they can contribute to increased genetic diversity in the C. albicans population.x

Pathogenesis

C. albicans becomes pathogenic only when its host’s immune system is already weakened. This is primarily a problem for people with HIV, people undergoing chemotherapy, and people who have received an organ transplant.xi However, C. albicans can also become pathogenic if the balance of beneficial bacteria is upset.xii This can happen, for example, when a patient is taking broad spectrum antibiotics. Other less common risk factors include: diabetes, use of corticosteroids, long-term use of dentures, and old age. Very young babies are also more susceptible to C. albicans infections.xiii

When the C. albicans infection is localized to the mouth and throat, it is called “thrush” (or oropharyngeal/ esophageal candidiasis, if you’re a doctor). This disease is characterized by whitish plaques on the tongue, gums, interior surface of the cheeks, and other mucus membranes in the mouth and throat. Inflammation around the plaques can cause redness and soreness and may make swallowing difficult. Additionally, infection may result in cracking around the corners of the mouth. For people with a healthy immune system, thrush can usually be prevented by practicing good oral hygiene.xiv

Candida albicans beginning to form a biofilm. By Y tambe (Y tambe’s file) [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The most common type of C. albicans infection is the “yeast infection” (genital/ vulvovaginal candidiasis), which occurs in the vagina. Yeast infections occur quite frequently: about three quarters of women have had a yeast infection at some point in their life (men can also get genital yeast infections, but it is much rarer). The most common trigger for developing a yeast infection is a change in hormone balance or acidity of the vagina. These changes occur during pregnancy, so pregnant women are more likely to get yeast infections. Additionally, risk factors associated with other types of C. albicans infections can make a yeast infection more likely. Symptoms of a yeast infection include itching, burning, and an unusual discharge, but these can also be associated with other genital diseases or urinary tract infections. Consequently, only a doctor can accurately diagnose a yeast infection.

Invasive or systemic candidiasis is the most dangerous type of C. albicans infection. In invasive candidiasis, the fungus gains access to the blood stream and/or various internal organs.xvi Because Candida species are common commensal organisms, they are the fourth most frequent cause of systemic infections that are acquired in hospitals. These infections can be very hard to treat; the mortality rate for invasive C. albicans infections is about 50%.xvii

Most of the time, invasive candidiasis follows the pattern of opportunistic infections. Those at risk for the disease include people with risk factors for other C. albicans infections as well as: patients with a central venous catheter, patients in an intensive care unit, and patients who have had surgery, especially gastrointestinal surgery.xviii In these cases, C. albicans has more opportunities to latch onto a piece of medical equipment and be transported to an internal organ.

Invasive candidiasis can also develop from a more normal C. albicans infection. This is most likely to happen in immunocompromised individuals. To become systemic on its own, C. albicans must penetrate the mucus membrane and invade deeper tissues. If hyphae of C. albicans can access a blood vessel, they can produce yeast cells and release them into the blood stream. The yeast cells will then be carried to other organs where they can invade more tissues.xix

Treatment

The symptoms of C. albicans infections are not very specific. Other yeasts, particularly others in the genus Candida, can produce disease symptoms very similar to those of C. albicans. As a result, diagnosis of a C. albicans infection can only be accomplished after examination of the infectious organism. C. albicans can be identified by looking at samples of biofilms or infected fluids (such as spittle or blood) under the microscope or by growing the infectious agent on differential culture media (seeing how the organism grows on petri dishes treated with different chemicals). Of course, C. albicans is a common commensal organism, so even a positive identification does not necessarily mean that it is causing the disease.xx

C. albicans infections are treated using various antifungals. For the easy cases, such as mild yeast infections, a single dose of an oral antifungal medication may be all that is needed (please note that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends against using over-the-counter antifungals to treat self-diagnosed yeast infections, as this may contribute to the rise of antifungal resistance if what you have is not actually a yeast infection).xxi Thrush is often treated with clotrimazole troches or nystatin suspension, which require patients to swish the medicine around their mouth and/or swallow it. Systemic antifungals may be required if the infection does not respond to the topical treatment.xxii Invasive candidiasis is likewise treated with systemic antifungals. Most infections can be dealt with by using antifungals like echinocandin or fluconazole or other chemically related drugs. More difficult infections may require treatment with amphotericin B xxiii (see FFF#161 for more on these drugs).

Do not use information in this post to self-diagnose or self-treat a medical complaint. Always consult a licensed medical doctor for proper diagnosis and treatment of a health issue.

See Further:

https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/index.html

http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/jan99.html

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3654610/

http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-3-642-39432-4_1

https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Candida_albicans_(Pathogenesis)

Citations

[i] Thomas J. Volk, “Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for January 1999,” Tom Volk’s Fungi, January 1999, http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/jan99.html; “Candidiasis,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 12, 2015, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/.

[ii] François L. Mayer, Duncan Wilson, and Bernhard Hube, “Candida Albicans Pathogenicity Mechanisms,” Virulence 4, no. 2 (February 15, 2013): 119–28, doi:10.4161/viru.22913.

[iii] Amy Whittington, Neil A. R. Gow, and Bernhard Hube, “From Commensal to Pathogen: Candida Albicans,” in Human Fungal Pathogens, ed. Oliver Kurzai, The Mycota 12 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014), 3–18, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-39432-4_1.

[iv] “Candida Albicans (Pathogenesis),” MicrobeWiki, February 11, 2016, https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Candida_albicans_(Pathogenesis).

[v] Mayer, Wilson, and Hube, “Candida Albicans Pathogenicity Mechanisms.”

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Whittington, Gow, and Hube, “1 From Commensal to Pathogen.”

[viii] Mayer, Wilson, and Hube, “Candida Albicans Pathogenicity Mechanisms.”

[ix] Whittington, Gow, and Hube, “1 From Commensal to Pathogen.”

[x] “Candida Albicans,” MicrobeWiki, July 22, 2013, https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/Candida_albicans.

[xi] “Oropharyngeal / Esophageal Candidiasis (‘Thrush’),” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, February 13, 2014, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/Candidiasis/thrush/.

[xii] Whittington, Gow, and Hube, “1 From Commensal to Pathogen.”

[xiii] “Oropharyngeal / Esophageal Candidiasis (‘Thrush’).”

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Mayer, Wilson, and Hube, “Candida Albicans Pathogenicity Mechanisms.”

[xvi] “Definition of Invasive Candidiasis,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 2, 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/invasive/definition.html.

[xvii] Mayer, Wilson, and Hube, “Candida Albicans Pathogenicity Mechanisms.”

[xviii] “Invasive Candidiasis Risk & Prevention,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 2, 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/invasive/risk-prevention.html.

[xix] Whittington, Gow, and Hube, “1 From Commensal to Pathogen.”

[xx] “Genital / Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC),” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, February 13, 2014, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/Candidiasis/genital/; “Oropharyngeal / Esophageal Candidiasis (‘Thrush’)”; “Diagnosis and Testing for Invasive Candidiasis,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 12, 2015, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/invasive/diagnosis.html.

[xxi] “Genital / Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC).”

[xxii] “Oropharyngeal / Esophageal Candidiasis (‘Thrush’).”

[xxiii] “Treatment for Invasive Candidiasis,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 2, 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/invasive/treatment.html.

![#140: Morchella angusticeps, the Black Morel of Eastern North America [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-medium-empty.png)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)