#161: Opportunistic Fungal Infections

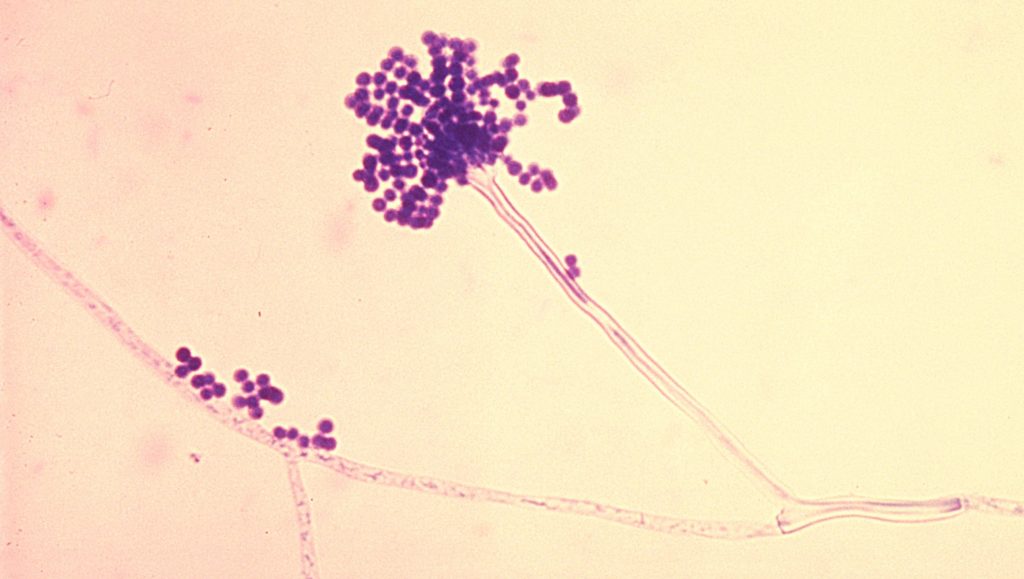

Aspergillus molds, like the one shown above, are common opportunistic pathogens. Public Domain photo, via via Wikimedia Commons

This October, I will be discussing human fungal infections. Although fungi can be extremely problematic for certain species of animals and plants, fungi cause humans relatively few problems. There are roughly 300 species of fungi that cause disease in humans, but the most common ones cause nuisance infections of the skin. About 20-25% of the global population has a fungal skin infection like ringworm, athlete’s foot, and similar diseases. Although annoying, these infections are not very severe. There are a few fungi that cause more severe diseases, but these are much less common. The most dangerous type of fungal infections are the opportunistic infections. These are caused by normally benign fungi that take advantage of unusual conditions, such as when a patient has a weakened immune system.i

Before I begin, I would like to point out that opportunistic fungal infections are rare and most are treatable. Because of the topic I am covering, things will seem scarier than they really are. If you have any concerns about fungal infection, please discuss them with your doctor. Do not put off getting medical treatment because of the slight risk of fungal infection.

Sources & Risk Factors

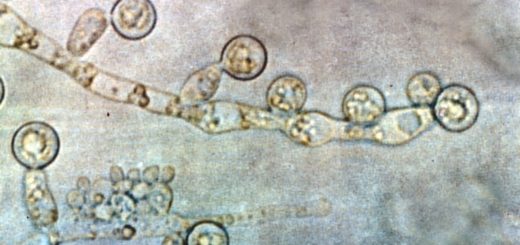

Fungi that cause opportunistic infections normally live in the environment. They include normally harmless fungi that naturally inhabit soil, plants, household surfaces, human skin, and even places like the mouth.ii The most common opportunistic fungal pathogens include: Candida spp., Aspergillus spp., and Mucor spp.iii Fungi in the genus Candida are commonly found on the skin and in mucous membranes but usually remain in a healthy balance.iv Aspergillus and Mucor species are common environmental molds that thrive both indoors and outdoors. People breathe in these spores every day and the vast majority of the time this does not cause any problems.v Because the fungi live primarily in the environment, they are almost never passed from person to person. Instead, new cases almost always represent a patient picking up the fungus from their own environment.vi

The greatest risk factor for contracting an opportunistic fungal infection is a weakened immune system. Fungi are major sources of infection for people with HIV/AIDS and similar diseases, people whose diabetes is not well controlled, those undergoing chemotherapy, and patients taking immunosuppressants.vii

Even with a weakened immune system, fungi still have to find a way into the body (except for those that are already there, like Candida spp.). Often, the entry point is through the lungs, since fungal spores are naturally found in the air. Alternatively, the fungi can make it past the skin by taking advantage of cuts, burns, and other injuries.viii

Opportunistic infections are so common in people with HIV that to be diagnosed with AIDS, a patient must test positive for HIV and develop an opportunistic infection. This is often a fungal infection such as thrush, but it can also be a bacterial or viral infection.ix

On a similar note, if you pay attention to commercials for rheumatoid arthritis medication, many of them contain a phrase like this: “tell your doctor if you live in a region where certain fungal infections are common.” Because rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease, many of the drugs used to treat it suppress the immune system.x Consequently, this can increase one’s chances of contracting a fungal infection.

Occasionally, a patient is infected by improperly sterilized medical equipment. This is of particular concern during transplants and when medical devices are placed inside the body. After a transplant, patients are usually given an assortment of drugs to prevent rejection of the foreign organ. Unfortunately, these drugs weaken the immune system and therefore make opportunistic fungal infections more likely.xi It is important to note that fungal infections following an organ transplant are rare; in such cases, only about 3% of patients are affected. However, these infections can be dangerous. Depending on the species of fungus, mortality ranges from 27% to 40%.xii

Fungal infections can result from injuries, but this rarely happens in healthy individuals. This type of infection is most likely to occur in patients with extreme or unusual injuries, such as severe burns or eye injuries from plant material.xiii Eye injuries can be particularly problematic because the eye is an immune privileged site, meaning that the immune system’s activity is greatly turned down in that area.xiv As a result, fungal infections have a greater chance of developing in the eyes, especially when twigs or splinters penetrate the eye (the relevant fungi naturally occur on these surfaces).xv

Treatment

Fungal infections are very difficult to treat, mainly because fungal cells are quite similar to human cells. Humans and fungi are both eukaryotes, which distinguishes them from other common infectious organisms like bacteria and viruses. Bacteria are prokaryotes, so their cell structure and chemical makeup are significantly different from our own. This makes it easy to develop drugs that attack bacterial cells while leaving human cells alone. Fungi, however, have a very similar cell structure and composition to humans. Accordingly, any drugs that kill fungal cells also do significant damage to human cells.xvi

There are four classes of drugs that are used to treat fungal infections that are widespread in the body: Amphotericin B, flucytosine, azole derivatives, and echinocandins. Historically, Amphotericin B was the go-to drug for treatment of fungal infections. However, it was very toxic and damaged the kidneys and bone marrow and upset the balance of chemicals in the blood. Amphotericin B was usually given via an IV over 2-3 hours, making even the process of administering the drug unpleasant. The less toxic and easier to administer azoles and echinocandins have largely replaced Amphotericin B as the first drugs of choice for fungal infections.xvii

Flucytosine is structured like a nucleic acid but it does not act like one. Instead, it has a toxic effect on fungal cells. Unfortunately, many fungi already have resistance to flucytosine, so it is usually used along with amphotericin B. Using two antifungals at the same time makes it less likely that the fungus will be able to gain more resistance or adapt to the treatment. However, this combination still has some nasty side effects. Flucytosine alone causes decreased blood cell production, harms the intestines, and damages the liver.xviii

Azoles are a class of chemicals that prevent fungal cells from producing ergosterol, a component of fungal cell membranes. These molecules have fairly mild side effects that for most people are not life threatening. Azoles are also readily absorbed by the digestive system, so they can be administered orally in a pill form. The main pitfall for azoles is that they interact with many other medications. Fluconazole is one of the least reactive azoles, but it is not as potent as other azoles.xix

Echinocandins block the action of glucan synthase, which prevents fungi from producing cell walls. Human cells do not have cell walls, so these molecules have very few side effects. Additionally, they react with very few medications. Unfortunately, these drugs can only be given through an IV.xx

Because many people who develop opportunistic fungal infections have weakened immune systems and are being treated for that condition, doctors must be very careful about which fungicide they prescribe. Another complication is that if a patient is allergic to one of these medicines or the patient’s particular strain of fungus is resistant to one, doctors have very few alternative treatments. This lack of diversity of antifungal drugs is one of the biggest problems facing medical professionals trying to treat fungal infections.

Case Study: 2012 Fungal Meningitis Outbreak

In 2012, there was an unusual outbreak of fungal meningitis related to contaminated medical supplies. During this outbreak, three lots of the steroid painkiller methylprednisolone acetate manufactured by New England Compounding Center were contaminated with fungi. This drug is administered as an epidural injection, meaning that as many as 1,400 patients could have had fungi injected directly into their spinal column. By the end of the outbreak, over 400 otherwise healthy people contracted fungal meningitis and over 30 patients died.xxi

This outbreak was a classic, if extreme, example of opportunistic fungal infections. The fungi involved in the outbreak were an Aspergillus species and an Exserohilum species.xxii Aspergillus species, as noted above, are known to cause infection in humans. Exserohilum, however, was not known as a pathogen at the time of the outbreak.xxiii Both of these fungi were acting as opportunistic pathogens during this event. They were growing in the environment when a lack of proper sterile procedure allowed them to be introduced into the medicine during production. They were then injected into peoples’ spinal cords, which bypassed the body’s defenses (such as the skin) that normally keep fungi out. These fungi continued to grow in the spinal column and eventually resulted in meningitis. Since this infection was contained inside the patients’ bodies, it could not be transmitted from one person to another.

The case also highlights just how difficult it can be to treat fungal infections. During this outbreak, the drugs of choice to fight these fungi were amphotericin B and voriconazole. Both of these drugs have nasty side effects, so the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised doctors not to treat patients unless their spinal fluid was cloudy. Fungal meningitis progresses slowly, so infected patients often had clear spinal fluid when symptoms appeared. This means patients had to make multiple trips to have their spinal fluid monitored for any change. Patients who did need treatment then had to make return trips to receive an IV drip for multiple months.xxiv

Do not use information in this post to self-diagnose or self-treat a medical complaint. Always consult a licensed medical doctor for proper diagnosis and treatment of a health issue.

See Further:

http://www.merckmanuals.com/home/infections/fungal-infections/overview-of-fungal-infections

http://www.microbiologybook.org/mycology/opportunistic.htm

https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/index.htm

http://abcnews.go.com/Health/fungal-meningitis-anatomy-outbreak/story?id=17667058

Citations

[i] “Types of Fungal Diseases,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, December 2, 2014, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/index.html; Blanka Halvickova, Viktor A. Czaika, and Markus Friedrich, “Epidemiological Trends in Skin Mycoses Worldwide,” Mycoses 51, no. Suppl. 4 (2008): 2–15; Sanjay G. Revankar and Jack D. Sobel, “Overview of Fungal Infections,” Merck Manuals Consumer Version, accessed October 7, 2016, https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/infections/fungal-infections/overview-of-fungal-infections.

[ii] “Types of Fungal Diseases.”

[iii] Art DiSalvo, “OPPORTUNISTIC MYCOSES,” Microbiology and Immunology On-Line, August 17, 2014, http://www.microbiologybook.org/mycology/opportunistic.htm.

[iv] “Candidiasis,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 12, 2015, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/index.html.

[v] “Aspergillosis,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 21, 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/aspergillosis/index.html; “Mucormycosis,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, December 30, 2015, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/mucormycosis/index.html.

[vi] Sanjay G. Revankar and Jack D. Sobel, “Overview of Fungal Infections.”

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] “Mucormycosis.”

[ix] “Opportunistic Infections,” AIDS.gov, November 16, 2010, https://www.aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/staying-healthy-with-hiv-aids/potential-related-health-problems/opportunistic-infections/.

[x] Eric Ruderman and Siddharth Tambar, “Rheumatoid Arthritis,” American College of Rheumatology, August 2013, http://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Rheumatoid-Arthritis.

[xi] Sanjay G. Revankar and Jack D. Sobel, “Overview of Fungal Infections.”

[xii] Shmuel Shoham and Kieren A Marr, “Invasive Fungal Infections in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients,” Future Microbiology 7, no. 5 (May 2012): 639–55, doi:10.2217/fmb.12.28.

[xiii] DiSalvo, “OPPORTUNISTIC MYCOSES”; “Fungal Eye Infections,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, December 24, 2015, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/fungal-eye-infections/index.html.

[xiv] A. W. Taylor, “Ocular Immune Privilege,” Eye 23, no. 10 (January 9, 2009): 1885–89, doi:10.1038/eye.2008.382.

[xv] “Fungal Eye Infections.”

[xvi] George Wong, “Fungi as Human Pathogens,” Department of Botany, Univeersity of Hawai’i at Mānoa, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.botany.hawaii.edu/faculty/wong/BOT135/LECT09.HTM.

[xvii] Sanjay G. Revankar and Jack D. Sobel, “Antifungal Drugs,” Merck Manuals Professional Edition, January 2014, http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/fungi/antifungal-drugs.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Sydney Lupkin, “Anatomy of a Meningitis Outbreak,” ABC News, November 8, 2012, http://abcnews.go.com/Health/fungal-meningitis-anatomy-outbreak/story?id=17667058; Alexandra Sifferlin, “5 Things You Need to Know About Fungal Meningitis,” Time, October 8, 2012, http://healthland.time.com/2012/10/08/5-things-you-need-to-know-about-fungal-meningitis/.

[xxii] Tom Wilemon, “Toxic Meds Only Weapon so Far against Fungal Meningitis,” USA TODAY, October 11, 2012, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2012/10/11/fungal-meningitis-treatment/1627363/.

[xxiii] Lupkin, “Anatomy of a Meningitis Outbreak.”

[xxiv] Wilemon, “Toxic Meds Only Weapon so Far against Fungal Meningitis.”

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

1 Response

[…] opportunistic fungal infections (FFF#161), fungi behave as they normally do, without drastically changing their cell structure or […]