#135: Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, Ash Dieback Disease

This emerging fungal disease of ash trees was first reported in 1992 in Poland. Over the past 24 years, Hymenoscyphus fraxineus has spread throughout Europe and (with the help of the invasive Emerald Ash Borer beetle) is now poised to eradicate ash trees from the entire continent.

The symptoms of ash dieback are fairly simple: wilting leaves, lesions in the bark, and death of twigs, branches, and shoots. Infected leaves wilt and display black blotches, primarily near the base and center of the leaf. On the stems, the fungus causes lesions to form in the bark that are small and lens-shaped. These lesions enlarge into cankers and eventually encircle the stem. This chokes off the stem’s vascular tissue, which prevents the transportation of food and water and thus kills the stem. In smaller branches, the fungus can encircle and kill the stem in a single growing season. Underneath the dying bark, the wood acquires a grayish-brown discoloration. A full-blown infection results in the death of many shoots and branches, thinning the tree’s crown considerably. Because of this, infected trees often sprout shoots from their bases. Discoloration, wilting, and dieback can have other causes as well, making positive identification of disease somewhat complicated. These symptoms are most devastating to younger trees, which have smaller branches that can be quickly choked off.

Any ash tree (Fraxinus spp.) can be infected by H. fraxineus, but some are more susceptible than others. Among European ash species, F. excelsior and F. angustifolia are highly susceptible to the disease, while F. ornus is moderately susceptible. In North America, F. nigra is highly susceptible, F. pennsylvanica is moderately susceptible, and F. americana is one of the least susceptible species. The Asian species F. mandschurica can also become infected, but it is not very susceptible. Ash Dieback likely originated on F. mandschurica trees, since they are one of the most resistant species. Currently, the disease can be found all across Europe but is limited to that continent.

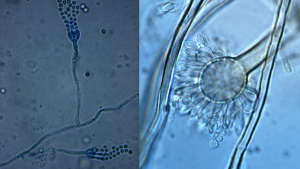

The life cycle of H. fraxineus begins when a spore lands on an ash leaf in the summer. The spore germinates and sends hyphae into the leaf’s tissues. Gradually, the fungus grows down toward the base of the leaf, into the stem, and towards the base of the tree. When the leaves fall off in the autumn, the fungus produces blackened structures (“pseudosclerotial plates”) near the base of the dead leaves. The fungus overwinters in these structures. The following summer, the fungus produces small mushrooms (stalked cups), which release sexual spores to infect new ash leaves.

Ash Dieback has primarily been spread through airborne spores and the transportation of diseased ash seedlings. It is unclear how H. fraxineus crossed the English Channel, but either method could have been responsible. Although the spores survive for only a few days, they are able to cross fairly large distances. However, large quantities of spores are needed to infect a plant. This makes local spread a more common occurrence than long-distance spread. It seems that the fungus is unlikely to be spread by other means, such as: by animals, on clothing, or in ash wood.

H. fraxineus belongs to the phylum Ascomycota, class Leotiomycetes, order, Helotiales, and family Helotiaceae. It was originally named Chalara fraxinea, but that was based on its asexual stage. As a result of this initial name, ash dieback is often called “Chalara dieback.” Once its sexual (mushroom) stage was discovered, it was renamed a few times and eventually received its current name. Its closest relatives are saprophytes, which indicates that H. fraxineus is capable of surviving without a living host. This makes disease management difficult, since decaying leaves can be a source of infection.

Luckily, there is some hope for Europe’s ash trees. First, not all infected trees die. Older trees are able to withstand infection for much longer than younger ones, possibly allowing forestry officials to save certain trees. In a similar vein, not all trees within a species are equally susceptible to the disease. In January of this year, scientists identified certain genes that indicate resistance to Ash Dieback. This could make it easier to pick out resistant varieties and allow officials to replant ash forests with resistant native trees. Finally, a study that came out in February found that a certain “enriched biochar” helped prevent the disease. This enriched biochar is a manufactured mix of charcoal, fungi, seaweed, and earthworm excrement. This mix can be spread around the base of an ash tree to help nourish the tree and protect against infection. Once again, this method can only be applied to a relatively small number of trees. Saving a few trees, however, would help preserve native forest diversity until resistance to the disease becomes widespread.

Despite the possible solutions listed above, a BBC article from late March was titled, “Ash tree set for extinction in Europe.” How could all the possible solutions fail so quickly? They didn’t. The problem is that ash trees face a second threat: the Emerald Ash Borer. This beetle, which is native to Asia, produces larvae that bore into the wood of ash trees and thus weaken and kill trees. European trees have no resistance to the beetle, and are thus dealing with two dire threats at the same time. Neither problem has a clear-cut solution, so it seems likely that any trees not killed by the fungus will be killed by the beetle. The study from March reasoned that this two-pronged attack would effectively eradicate all of Europe’s ash trees, much the same way that Dutch elm disease (another fungal disease) wiped out all the elm trees.

Losing a tree species has dire consequences for forest biodiversity. In Europe, there are over 1,000 species of animals (birds, mammals, and insects), fungi, and lichens that are associated with ash trees. Of these, over 100 are likely to go extinct if ash trees disappear from the landscape. In North America, I am familiar with one mushroom species (Boletinellus merulioides) and an associated insect (the Leafcurl Ash Aphid) that live only on ash trees.

Could the same thing happen in North America? The Emerald Ash Borer is already well-established in the Eastern United States. Adding a disease into the mix would probably hasten the decline of our ash trees as well. Fortunately, the most likely way for ash dieback to reach North America is through infected trees brought over from Europe. Knowledge of the disease, proper quarantine procedure, and the long distances involved will likely prevent ash dieback from reaching our continent.

See Further:

http://www.forestry.gov.uk/ashdieback

https://www.rhs.org.uk/advice/profile?PID=779

http://www.agriculture.gov.ie/forestservice/ashdiebackchalara/

http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-35876621

http://www.pestalert.org/viewNewsAlert.cfm?naid=86

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

1 Response

[…] it often appears on ash trees (since there are quite a few dead European ashes these days, see FFF#135).4,6,7 The brackets appear directly from the wood at the bases of dead or dying trees and in […]