#142: Pluteus cervinus, the Deer Mushroom

Pluteus cervinus grows in well-rotted wood and produces large mushrooms with pink spores and free gills. Other features of the mushrooms are variable, but they usually have a light brown cap, white stipe with brown streaks, and a faint radish-like odor. Photo by Stu’s Images [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Description

On the surface, the Deer Mushroom is not very interesting. It is a medium-sized to large mushroom with a light brown pileus, white to pink gills, and a white stipe. P. cervinus grows 2.5-13cm across and 5-13cm tall (but can get bigger), which is the only visually remarkable feature of this mushroom.1,2,4,5

The Deer Mushroom’s cap is smooth and is usually some shade of light brown, though field guides often prefer to describe the color as “fawn” in reference to its common and scientific names (cervinus is derived from the scientific name for the deer family). The color is variable and can be nearly white to dark brown, sometimes with tones of grey or olive. Deer Mushrooms tend to have darker colors towards the center of the pileus. You can sometimes find tiny scales or fibers near the center of the otherwise smooth cap. Specimens often feature streaks of darker brown that radiate out from the cap’s center. The pileus starts out convex and opens up to be nearly flat with a large, raised area (called an “umbo”) over the center of the pileus.1–5

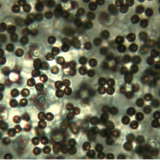

The underside of the cap features white to pink gills that radiate out from a central stipe. The gills start out white but become pink to orangish-pink as the spores mature. A key feature for identification is that the gills are free from the stipe. The gills approach the stipe but stop just short of where the stipe meets the pileus. Mature gills turn pinkish because they produce pinkish spores; the spore print of the Deer Mushroomis some version of pink, from pale pink to salmon-pink to brownish-pink.1–5

The stipe of P. cervinus is white, about 1cm thick, and usually features brownish streaks. It is mostly cylindrical in shape but may expand somewhat at the base. The stipe is smooth and white, except for the small, brown streaks or fibers that are more commonly found in older specimens or towards the bottom of the stipe.1–5

P. cervinus has white, soft flesh that does not bruise when damaged. Its odor and taste are rather mild and reminiscent of radishes.1–5 One time that I found this mushroom, it acquired a very pleasant, rose-like odor upon drying. No field guides mention this feature, so my experience could have been a random fluke (I also found a lot of tiny crystals under the microscope that were likely also produced during the drying process).

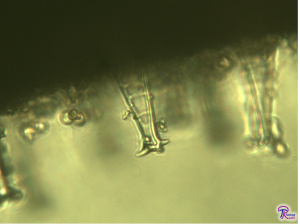

P. cervinus has some of the most beautiful cystidia of all mushrooms. The sterile cells that stick out conspicuously above the gill surface are bowling pin shaped and end with a cluster of distinctive prongs.

The most striking feature of the Deer Mushroom is its uniquely-shaped cystidia, which you need a microscope to see. Cystidia are large cells that project from various mushroom surfaces and do not produce spores. The cystidia on P. cervinus are found on the gill surfaces and edges (which technically makes them “pleurocystidia” and “cheilocystidia,” respectively). These cystidia are much taller than the surrounding, spore-producing cells (called “basidia”) and so are easily visible under the microscope. Many mushrooms have cystidia, but what sets P. cervinus apart is that its bowling pin-shaped cystidia are topped with multiple, short points.1–5 These beautiful, antler-like structures resulted in both the common name “Deer Mushroom” and the species name cervinus.6

Ecology

P. cervinus can be found in temperate forests of North America and Europe, where it grows from well-rotted logs, usually on hardwood but sometimes on conifer wood. The mushrooms can seem terrestrial if they are decomposing buried wood. In North America, they grow east of the Rocky Mountains and south of 45°N (roughly the lower ¾ of the United States), but there is also a small population around San Francisco. The mushrooms start appearing during morel season and continue to fruit through the fall.1–5 In California, the season begins in the fall and continues through mid-winter.1 They are most noticeable early in the year, when other large gilled mushrooms have not yet ventured out.

Similar Species

The Deer Mushroom described in North American field guides actually encompasses a few closely related species of Pluteus. P. rangifer tends to have a darker pileus, usually features more scales/fibers, and is found in boreal forests, which are found well above 45°N. Most West Coast specimens represent P. exilis, which is also darker and scalier. P. petastus usually has a lighter pileus, is often found fruiting in mulch (P. cervinus rarely fruits from mulch), and features numerous “intermediate cystidia,” which are spindle-shaped and do not yet have the characteristic “antler” points.4

The three species listed above are the most common species of the P. cervinus species group, but there are a handful of others. Differentiating between these species requires use of a microscope to compare features like morphology of cystidia, spore size, and presence/absence of clamp connections in the pileus.7 If you want to find the correct name for your mushroom, use the great keys available from MushroomExpert.com or Le blogue Mycoquébec (the latter is in French).

Other continents might also have a variety of species masquerading as P. cervinus. I don’t know whether that is the case, so if you live outside North America check some of your local sources for the most accurate information.

There are a few other pink-spored fungi that could be confused with P. cervinus. Volvariella species also grow on wood but – as the genus name suggests – each has a sac-like membrane called a “volva” surrounding the base of its stipe. Entoloma species have attached gills and grow on the ground, often close to decomposing wood but not on the wood itself. Many Entolomas are poisonous, so make sure any Deer Mushrooms you collect have truly free gills and are growing directly from wood.1,6 If you take the time to do a spore print, you won’t have to worry about other possible look-alikes.

Although it is not always noticeable, the Deer Mushroom has a broad bump called an “umbo” over the center of the pileus. Compare this picture to the one at the top of the page to see how variable the Deer Mushroom’s pileus can be.

Edibility

The Deer Mushroom is a known edible species, although there are scattered reports of it causing gastrointestinal upset.1–4 The other species in the group are all listed as either “edible” or “edibility unknown.”8–14 Since these species are so similar, mushroom hunters have probably been eating them as the “Deer Mushroom” for a long time without realizing there were different species. If that is the case, then all the species in this group are probably equally edible. On the other hand, the smattering of reports of gastrointestinal upset could indicate that one or two of the rarer species are poisonous.

Before eating this mushroom, it would be prudent to check with your local mushroom club (mushroom clubs know more about the edibility of local mushrooms than anyone else) to see if they worry about species divisions within the Deer Mushroom group. If they don’t, you can eat your Deer Mushrooms without identifying them down to species.

The Deer Mushroom does not have very many fans because of its uninspiring flavor and brittle texture.6,15 However, since it is one of the few edible mushrooms found in spring people can get excited about it when they don’t find anything else on their morel forays.

P. cervinus spoils very quickly in warm weather, so it should be refrigerated as soon as possible after being picked. Insects enjoy eating these mushrooms and older specimens are often quite buggy. Therefore, only young and fresh mushrooms should be picked.2 I find that Deer Mushrooms are best in spring because the cooler weather limits insect activity and the mushrooms remain fresher longer.

The Deer Mushroom has one interesting culinary quality: it smells faintly of radishes. To preserve that unique aroma, try stewing the mushroom instead of frying it. The radish-like flavor of P. cervinus goes well with vegetable and fish dishes.15

Taxonomy

The pink spore print and free gills of P. cervinus and other mushrooms in the group are distinctive characteristics of the family Pluteaceae (FFF#184). Despite the fact that P. cervinus is being split into multiple species, the mushroom’s higher classification seems very stable. In other words, mycologists have a good idea of what defines Pluteus even if they have a poor grasp of the species-level divisions.

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Division (Phylum) | Basidiomycota |

| Subdivision (Subphylum) | Agaricomycotina |

| Class | Agaricomycetes |

| Subclass | Agaricomycetidae |

| Order | Agaricales |

| Family | Pluteaceae |

| Genus | Pluteus |

| Species | Pluteus cervinus (Schaeff.) P. Kumm.16 |

This post is not part of a key and therefore does not contain enough information to positively identify any mushroom. When collecting for the table, always use a local field guide to identify your mushrooms down to species. If you need a quality, free field guide to North American mushrooms, I recommend Michael Kuo’s MushroomExpert.com. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out!

See Further:

http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/june98.html

http://www.mushroomexpert.com/pluteus_cervinus.html

http://www.messiah.edu/oakes/fungi_on_wood/gilled%20fungi/species%20pages/Pluteus%20cervinus.htm

http://www.first-nature.com/fungi/pluteus-cervinus.php

http://www.mykoweb.com/CAF/species/Pluteus_cervinus.html

http://foragerchef.com/the-fawndeer-mushroom-pluteus-cervinus/

Citations

- Wood, M. & Stevens, F. California Fungi—Pluteus cervinus. Available at: http://www.mykoweb.com/CAF/species/Pluteus_cervinus.html. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Labbé, R. Pluteus cervinus / Plutée couleur de cerf. Les champignons du Québec (2016). Available at: https://www.mycoquebec.org. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- O’Reilly, P. Pluteus cervinus P. Kumm. – Deer Shield. First Nature Available at: https://www.first-nature.com/fungi/pluteus-cervinus.php. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Kuo, M. Pluteus cervinus. MushroomExpert.Com (2015). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/pluteus_cervinus.html. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Emberger, G. Pluteus cervinus. Fungi Growing on Wood (2008). Available at: https://www.messiah.edu/Oakes/fungi_on_wood/gilled%20fungi/species%20pages/Pluteus%20cervinus.htm. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Volk, T. J. Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for June 1998. Tom Volk’s Fungi (1998). Available at: http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/june98.html. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Kuo, M. The Genus Pluteus. MushroomExpert.Com (2015). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/pluteus.html. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Wood, M. & Stevens, F. California Fungi—Pluteus petasatus. The Fungi of California Available at: http://www.mykoweb.com/CAF/species/Pluteus_petasatus.html. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Labbé, R. Pluteus hongoi / Plutée de Hongo. Les champignons du Québec (2016). Available at: https://www.mycoquebec.org. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Labbé, R. Pluteus elaphinus / Plutée des cervidés. Les champignons du Québec (2018). Available at: https://www.mycoquebec.org. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Labbé, R. Pluteus brunneidiscus / Plutée à disque brun. Les champignons du Québec (2016). Available at: https://www.mycoquebec.org. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Labbé, R. Pluteus primus / Plutée précoce. Les champignons du Québec (2017). Available at: https://www.mycoquebec.org. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Labbé, R. Pluteus methvenii / Plutée de Methven. Les champignons du Québec (2016). Available at: https://www.mycoquebec.org. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Labbé, R. Pluteus rangifer / Plutée du caribou*. Les champignons du Québec (2016). Available at: https://www.mycoquebec.org. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Bergo, A. The Fawn or Deer Mushroom. Forager Chef (2013). Available at: http://foragerchef.com/the-fawndeer-mushroom-pluteus-cervinus/. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

- Pluteus cervinus. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?TableKey=14682616000000067&Rec=58193&Fields=All. (Accessed: 25th May 2018)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

Thank you very much for this info on the Deer Mushroom. I have been trying to identify this mushroom because it has appeared on my property many times, and I’d love to be able to eat it, if possible. In addition, I can easily tell you have an expert level qualification.