#089: Cerioporus squamosus, the Dryad’s Saddle

Cerioporus squamosus is a beautiful mushroom that can be easily recognized by its pale pileus with large brown scales. This large mushroom is especially satisfying to find in the spring when you’re striking out with morel hunting.

Cerioporus squamosus (a.k.a. Polyporus squamosus) is a beautiful polypore that reaches impressive sizes. It is whitish with brown flecks on the top and is probably the largest mushroom you’ll find in the spring. It appears on dead trees and logs and is quite eye-catching thanks to its size and pale colors. C. squamosus is commonly known as the “Dryad’s Saddle,” “Pheasant Back Mushroom,” or “Hawk’s Wing” (this last name is the least common). The first name – which is my personal favorite – derives from the mushroom’s shape; its brackets seem to be perfectly sized and positioned to form a little seat for a weary tree nymph (dryad). The other two names refer to the mushroom’s coloration; a pale surface flecked with triangles of brown looks remarkably similar to the back of a female pheasant or the wing of a hawk.1–3

Description

Cerioporus squamosus is a shelf fungus that produces large, kidney-shaped to almost circular brackets. Unlike most shelf fungi, the Dryad’s Saddle can form a relatively long stipe that grows 1-12cm tall. This is still small in comparison to the pileus, which grows 5-30cm (and sometimes up to 60cm) across. You usually find multiple fruitbodies growing from the same stump, often overlapping, but the mushrooms occasionally fruit alone.3–7

Young Dryad’s Saddles are shaped like a fat flask; the base is bulbous and supports a fairly thick whitish stipe that is topped with a thin ring of a pileus. In this stage, the base is often covered with a smooth brown crusty layer that breaks apart as the mushroom grows. Fragments from this layer can stick to the stipe and be carried away from the base as the stipe elongates.3–7

As the mushroom matures, the stipe thickens and the pileus gets larger. At this stage, the mushroom is shaped roughly like a funnel; the stipe gets thinner toward the base and the pileus usually has a small depression over the stipe. The margin of the pileus tends to be slightly curved underneath the mushroom throughout development, giving the Dryad’s Saddle a rather graceful appearance. Despite its saddle-like shape, I’ve never come across a dryad sitting on one of these mushrooms. I guess there’s no harm in looking, though – I may get lucky someday!3–7

The most striking feature of the Dryad’s Saddle is the presence of large brown scales on the surface of the pileus. Most of the pileus is whitish to tan, which really makes the large dark brown scales stand out. These scales (a.k.a. squamules, thus the species name “squamosus”) are flattened to the pileus and radiate out from a central point, often forming uneven rings. Underneath the pileus, the pore surface is off-white to creamy and runs down the stipe.3–7

The pileus of C. squamosus is remarkably similar in coloration to a female common pheasant (Phasianus colchicus). Because of this similarity, some people call this mushroom the “Pheasant Back Mushroom.” Photo by Andy Vernon [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons (cropped).

Ecology

C. squamosis is parasitic and saprobic on hardwood trees. 3–7 In North America it particularly likes silver maple, box elder, and quaking aspen, while in Europe it often appears on ash trees (since there are quite a few dead European ashes these days, see FFF#135).4,6,7 The brackets appear directly from the wood at the bases of dead or dying trees and in various places on fallen logs. Most often, the Dryad’s Saddle fruits during spring, but the fungus sometimes fruits in the summer or fall. 3–7 If the conditions are right, you can also find fresh specimens of C. squamosus in winter. The mushrooms survive for only one year, although they can remain for half a year or so if the conditions are right.4 Under less than ideal conditions the mushrooms will disappear within a few weeks due to insect activity and decay.6

As the Dryad’s Saddle ages, its pileus fades to whitish, its pores yellow, and its stipe becomes black and velvety.

Similar Species

The Dryad’s Saddle is a unique polypore that has no real lookalikes (at least in North America and Europe). When pressed to discuss possible points of confusion, field guide authors suggest other polypores with a similar shape or that fruit in the spring, such as Piptoporus betulinus or Polyporus alveolaris. Both of those mushrooms tend to be smaller than C. squamosus and neither has large showy scales on the cap surface.2,4 Large whitish polypores like Berkeley’s Polypore (Bondarzewia berkeleyi) and the Black Staining Polypore (Meripilus sumstinei) are also similar in size and shape, so you could mistake one for an old Dryad’s Saddle where the scales have faded away and aren’t very noticeable. However, those two mushrooms tend to grow on the ground next to dead or dying trees rather than directly from the wood and neither features a stipe that turns black before the rest of the mushroom.8,9

Edibility and Uses

C. squamosus is edible when young, but the mushroom doesn’t have many fans. The Dryad’s Saddle is not very flavorful and tends to be tough. If you want to try eating the fungus, make sure you pick it when it is very young. It’s best before the stipe starts turning black and you will only want to eat the parts that you can easily slice through with a knife. The older the mushroom gets, the more fibrous and corky its texture becomes.1–3,7,8

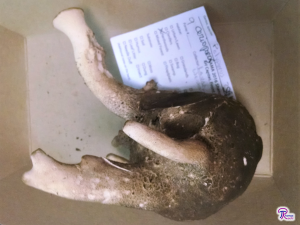

Sometimes, unfavorable weather conditions cause C. squamosus to contort itself into unusual shapes. The mushroom above most likely formed due to a sequence of wet-dry-wet-dry weather.

The fun part about the Dryad’s Saddle is its watermelon-like odor (and the fact that you can usually find it even when you’re having a bad morel season). When cooking the mushroom, you want to try and conserve this flavor as much as possible. Frying is the best option for this and also brings out a bit of a lemony flavor.2,10,11 Another popular method is pickling them as you would watermelon rind. Older specimens can be used to create a soup stock, but you really can’t eat them directly.2,10

If you’re not into eating mushrooms, you can also use the Dryad’s Saddle to make paper (see FFF#084).1,12 Once again, the younger specimens work best. The young mushrooms create a yellowish paper that is somewhat translucent.12 Older specimens would probably also work, but the paper would likely be thicker and coarser because of the more robust fibers.

Taxonomy

The Dryad’s Saddle was originally named Boletus squamosus in 1778. As mycologists narrowed the definition of Boletus (which now contains only certain boletes, see FFF#028), the Dryad’s Saddle was transferred to the genus Polyporus in 1821.6,13 Now, it’s being transferred to the genus Cerioporus. That name was originally applied in 1886, but it was only revived after DNA analysis showed that the Dryad’s Saddle and some other species were significantly different from the rest of the species in Polyporus that they had to be moved to their own genus.13,14

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Division (Phylum) | Basidiomycota |

| Class | Agaricomycetes |

| Order | Polyporales |

| Family | Polyporaceae |

| Genus | Cerioporus |

| Species | Cerioporus squamosus (Huds.) Quél.13 |

This post is not part of a key and therefore does not contain enough information to positively identify any mushroom. When collecting for the table, always use a local field guide to identify your mushrooms down to species. If you need a quality, free field guide to North American mushrooms, I recommend Michael Kuo’s MushroomExpert.com. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out!

See Further:

http://www.mushroomexpert.com/polyporus_squamosus.html

http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/may2001.html

https://www.messiah.edu/Oakes/fungi_on_wood/poroid%20fungi/species%20pages/Polyporus%20squamosus.htm

http://foragerchef.com/the-cucumber-mushroom-dryads-saddlepheasant-back/

Citations

- Volk, T. J. Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for May 2001. Tom Volk’s Fungi (2001). Available at: http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/may2001.html. (Accessed: 11th May 2018)

- Spahr, D. Dryad’s Saddle: Pheasant Back Mushroom, Hawks Wing (Polyporus squamosus). Mushroom-Collecting.com Available at: http://mushroom-collecting.com/mushroomdryad.html. (Accessed: 11th May 2018)

- Labbé, R. Cerioporus squamosus / Polypore écailleux. Les champignons du Québec (2016). Available at: https://www.mycoquebec.org. (Accessed: 11th May 2018)

- Kuo, M. Polyporus squamosus. MushroomExpert.Com (2015). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/polyporus_squamosus.html. (Accessed: 11th May 2018)

- Emberger, G. Polyporus squamosus. Fungi Growing on Wood (2008). Available at: https://www.messiah.edu/Oakes/fungi_on_wood/poroid%20fungi/species%20pages/Polyporus%20squamosus.htm. (Accessed: 11th May 2018)

- O’Reilly, P. Polyporus squamosus (Huds.) Fr. – Dryad’s Saddle. First Nature Available at: https://www.first-nature.com/fungi/polyporus-squamosus.php. (Accessed: 11th May 2018)

- Polyporus squamosus. Midwest American Mycological Information Available at: http://www.midwestmycology.org/Mushrooms/Species%20listed/Polyporus%20squamosus%20species.html. (Accessed: 11th May 2018)

- Kuo, M. Meripilus sumstinei. MushroomExpert.Com (2010). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/meripilus_sumstinei.html. (Accessed: 11th May 2018)

- Kuo, M. Bondarzewia berkeleyi. MushroomExpert.Com (2004). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/bondarzewia_berkeleyi.html. (Accessed: 11th May 2018)

- Bergo, A. Dryad’s Saddle or Pheasant Back Mushroom. Forager Chef (2013). Available at: http://foragerchef.com/the-cucumber-mushroom-dryads-saddlepheasant-back/. (Accessed: 11th May 2018)

- Rockland-Miller, A. The Oft-Overlooked Dryad’s Saddle. The Mushroom Forager (2011).

- King, A. & Watling, R. Paper Made From Bracket Fungi. North American Mycological Association (1997). Available at: https://www.namyco.org/paper_made_from_bracket_fungi.php. (Accessed: 11th May 2018)

- GSD Species Synonymy: Current Name: Cerioporus squamosus (Huds.) Quél., Enchir. fung. (Paris): 167 (1886). Species Fungorum Available at: http://www.speciesfungorum.org/GSD/GSDspecies.asp?RecordID=163056. (Accessed: 11th May 2018)

- Cerioporus. Wikipedia (2018).

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

Are these mushrooms safe to eat

Yes, Dryad’s Saddle is safe to eat, but you have to cook it first. I’ve had some GI upset after eating older ones, so I recommend sticking to young fresh specimens.