#202: Aflatoxins

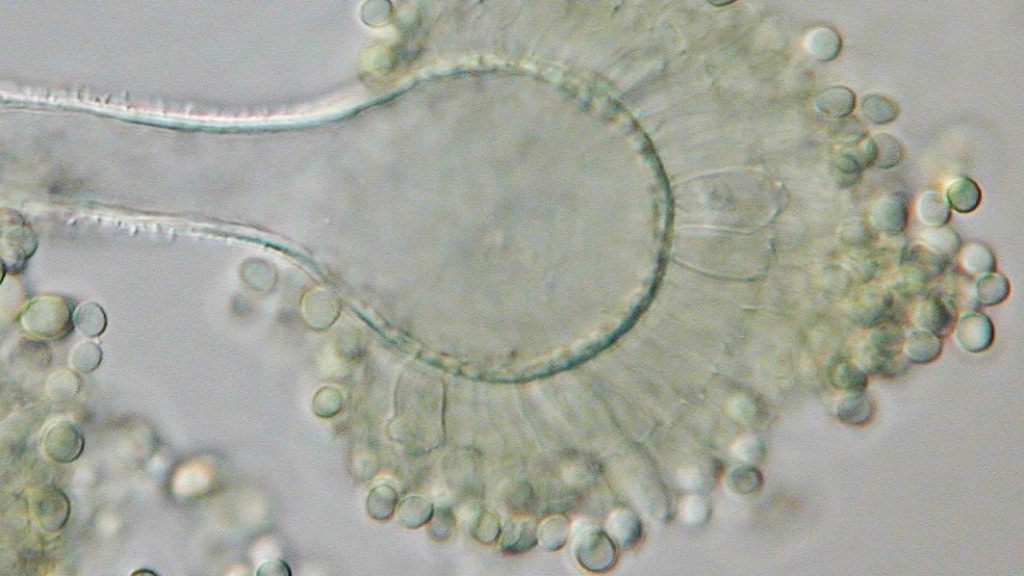

Aspergillus species, such as the one pictured above, commonly contaminate food with aflatoxins. Photo by Medmyco [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons (cropped, rotated).

Sources

Aflatoxins are produced by some strains of the fungi Aspergillus flavus, A. parasiticus, A. niger, and A. nomius.1 All four fungi are common molds found across the globe, but most aflatoxins in food come from A. flavus and A. parasiticus, which prefer hot and humid climates.2–4 These fungi infect and produce aflatoxins in a wide variety of hosts, including: corn (maize), rice, tree nuts, peanuts, oil seeds, dried fruit, cassava, livestock feed, some spices, and many other food plants. Aflatoxins can also be found in dairy products made with milk from animals that were fed aflatoxin-contaminated feed.1,4–6

Fungal contamination of food primarily happens either during crop growth or after harvesting.1 A. flavus and A. parasiticus can grow as pathogens, so they will infect plants if given a chance. Crops are most susceptible to infection when stressed by heat, drought, and insect damage.2 After the harvest, the fungi have a second opportunity to attack while produce is being stored. Crops stored in hot and wet conditions promote the growth of A. flavus and A. parasiticus.1,4

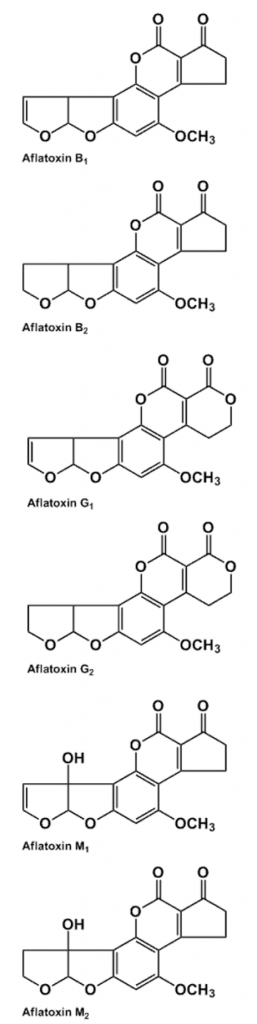

The six major aflatoxins are shown above. Aflatoxin B1 (top) is the most harmful of the group. Aflatoxins M1 and M2 are derivatives of other aflatoxins that have been modified after an animal ate them. Photo by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, edited.

Structure and Mechanism

Most aflatoxins come in one of four forms: B1, B2, G1, or G2. These alphanumeric labels may seem random, but they actually reflect slight differences in the aflatoxins’ physical properties. “B” aflatoxins glow blue under ultraviolet light, while “G” aflatoxins glow green. The numbers were assigned based on how they separated in thin layer chromatography: within each color group, the aflatoxin designated “1” traveled farther than the one designated “2”. There are also two aflatoxin derivatives that appear in food, which are designated M1 and M2. These were assigned “M” because they were originally isolated from milk. The numbers once again relate to thin layer chromatography.1,2,7

Of all these aflatoxins, B1 is the most dangerous.4 In fact, it is one of the most potent carcinogens on the planet.7 The problem with B1 is that it enters liver cells and is converted into a chemical called “aflatoxin B1-8,9-exo-epoxide” by enzymes in those cells. This aflatoxin derivative efficiently attaches to DNA at guanine residues (other aflatoxins produce similar compounds that also bind DNA, but not as efficiently). When this happens, it confuses the machinery that copies DNA before cell division. Instead of reading a guanine (G), the replication machinery reads the modified base as a thymine (T).8,9

Depending on where this substitution happens, it may or may not cause problems. Unfortunately, aflatoxins often cause mutations at a certain spot in a gene called “p53.” This gene is a tumor suppressor, so its main job is to make sure cells don’t grow and divide too quickly. A single G to T substitution at a certain point in p53 causes the gene to stop working, which reduces the cell’s ability to regulate its growth. This greatly increases the likelihood that the cell will develop into cancer.4,7,9

In addition to being carcinogenic, aflatoxins are also toxic to cells. The compounds can cause cell death, but the pathways responsible for that outcome have not received as much study. Presumably, the aflatoxins and/or their derivatives bind to and destroy various cell proteins. If the cell loses too many proteins, its cellular machinery will stop working and it will die.8,9

Symptoms

The first recognized cases of aflatoxin poisoning were in England in 1960, where over 100,000 turkeys as well as some ducklings and pheasants died mysteriously. Scientists discovered that the animals had all been fed peanut meal from Brazil. Further investigation led to the discovery of a new fungus, Aspergillus flavus, and the toxin aflatoxin (“afla” is a shortening of A. flavus).1,2

In humans, aflatoxins can cause short-term and long-term symptoms. High doses of aflatoxins can trigger the disease “aflatoxicosis” after just a few days. Mild aflatoxicosis may include nothing more than nausea, headache, and a rash. However, severe cases can completely disrupt liver function and lead to liver failure. This progression causes symptoms including gastrointestinal distress, anemia, hemorrhaging, and jaundice, among others. Aflatoxicosis has a mortality rate somewhere between 25% and 60%. Fortunately, outbreaks of aflatoxicosis are relatively rare; there were only four recorded outbreaks between 1960 and 2005.1,7,8

Exposure to low levels of aflatoxins over a long period of time causes more subtle symptoms, most of which are related to decreasing liver functionality. These symptoms slowly accumulate over time and include: reduced blood coagulation, swelling of the liver (toxic hepatitis), stunted growth in children, liver cancer in the form of hepatocellular carcinoma, and probably a suppressed immune system (this has been seen in animal models but hasn’t been verified in humans).1,7,8

Symptoms are highly variable in both the short-term and long-term versions of the disease. Many factors are involved that can support or detract from an individual’s ability to deal with aflatoxins. Some of these are: age (children are more susceptible), health (diseases like hepatitis B can make the liver damage worse), nutrition, sex, and length of exposure.1,7

Impacts

Aflatoxins do not have much of an impact on people living in developed countries such as the United States. These countries tend to have effective regulations and carry out regular testing to ensure that consumers are exposed to as little aflatoxin as possible. The FDA requires that all animal feeds except corn and all food destined for human consumption contain less than 20 parts per billion (ppb) of aflatoxins. Milk has even more stringent regulations: it must contain less than 0.5ppb!1 Children drink a lot of milk and are more susceptible to aflatoxins, so aflatoxins in milk are a major source of concern.6 Corn for animal feed is allowed to have higher levels, depending upon what kind of animal is being fed.1,2 These regulations seem to be working, since the U.S. has never had an aflatoxin-associated disease outbreak in humans (although, some dogs and cats died from outbreaks in 1998 and 2005).7

Of course, testing isn’t perfect, especially when it comes to products like nuts whose quality can vary widely within a batch.7 Here, consumers can help protect themselves from aflatoxins by deciding not to eat a moldy nut, even if came in the bag. Of course, this strategy does not work for products like peanut butter, where many nuts have been ground together. Fortunately, most American companies that manufacture peanut butter and similar products hold themselves to higher standards than the FDA requires.6

Aflatoxins cause much more problems in developing countries. Many governments in southeast Asia and central Africa do not have the resources to regulate aflatoxins, so millions of people in those regions are suffering from the long-term effects of aflatoxin poisoning.5,7 For example, aflatoxins cause about 40% of liver cancers in Africa, but cause only 5-30% of cases in the rest of the world.5

Although it seems like the problem of aflatoxin contamination could be solved through education and regulation, aflatoxins trap small scale farmers in a difficult economic situation. Farmers who don’t have the resources to prevent aflatoxin contamination cannot sell their products on international markets because of the stringent restrictions developed countries use. The farmers then have two options: throw out the contaminated crops or sell them locally. If selling their crops is the only way they can put food on their own table, then they will sell their contaminated crops locally. This cycle is especially problematic when the food in question is a staple food, such as corn (maize), rice, or cassava.10

Solutions

Reducing exposure to aflatoxins among the poor in developing nations is a difficult problem that will have to be addressed from multiple angles. The Partnership for Aflatoxin Control in Africa created a long list of potential strategies, most of which are focused on improving education and encouraging the use of products designed to combat aflatoxin (where economically feasible). Through education, small farmers could learn techniques to prevent fungal growth and learn which crops are less likely to be contaminated.10

Unfortunately, there are not many options for getting rid of aflatoxins once they are in produce. In fact, the FDA has not approved any methods for destroying or deactivating aflatoxins. The molecules are highly resistant to heat and chemicals, so they are not destroyed by cooking and most treatments have only marginal success at removing the toxins. Interestingly, the process for preparing tortillas does quite a good job at removing aflatoxins.1,2

Another option is to feed humans (especially babies) or animals binding agents – such as calcium chlorophyllin clay or aluminosilicates – along with the aflatoxin-containing food. These compounds can bind mycotoxins in the gastrointestinal tract, but have not been approved for this purpose in all countries.2,10

Recently, scientists have been working on more technically advanced ways to tackle this problem. One group created a strain of corn (maize) genetically engineered to produce small bits of RNA that bind to and deactivate genes in the fungus needed to produce aflatoxins.11 Another team is using a game called Foldit to get help from the public in designing enzymes that could break down aflatoxin.12 Neither of these possible solutions kills the fungus, but they do solve the toxicity problem. Of course, it remains to be seen whether or not these will be cost effective for use in developing countries. (See Spring and Fall 2017 News Updates for more.)

Do not use information in this post to self-diagnose or self-treat a medical complaint. Always consult a licensed medical doctor for proper diagnosis and treatment of a health issue.

See Further:

http://poisonousplants.ansci.cornell.edu/toxicagents/aflatoxin/aflatoxin.html

https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/FoodborneIllnessContaminants/UCM297627.pdf (very long pdf)

http://extension.missouri.edu/p/G4155

http://toxicology.usu.edu/endnote/mechanisms-of-alfatoxin.pdf (pdf, scientific paper)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3629261/ (scientific paper)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2802673/ (scientific paper)

Citations

- AFLATOXINS: Occurrence and Health Risks. Cornell University Department of Animal Science – Plants Poisonous to Livestock (2015). Available at: http://poisonousplants.ansci.cornell.edu/toxicagents/aflatoxin/aflatoxin.html. (Accessed: 10th November 2017)

- Wrather, A. et al. Aflatoxins in Corn. University of Missouri Extension (2010). Available at: http://extension.missouri.edu/p/G4155. (Accessed: 10th November 2017)

- Aflatoxins in food. European Food Safety Authority Available at: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/aflatoxins-food. (Accessed: 10th November 2017)

- HAMID, A. S., TESFAMARIAM, I. G., ZHANG, Y. & ZHANG, Z. G. Aflatoxin B1-induced hepatocellular carcinoma in developing countries: Geographical distribution, mechanism of action and prevention. Oncol Lett 5, 1087–1092 (2013).

- What is the aflatoxin problem? Partnership for Aflatoxin Control in Africa Available at: http://www.aflatoxinpartnership.org/?q=aflatoxins. (Accessed: 10th November 2017)

- Kuldau, G. Mycotoxins: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. (2017).

- Trucksess, M. W. Aflatoxins. in Bad Bug Book: Handbook of Foodborne Pathogenic Microorganisms and Natural Toxins (eds. Lampel, K., Al-Khaldi, S. & Cahill, S. M.) 231–236 (Food and Drug Administration, 2012).

- Eaton, D. L. & Gallagher, E. P. Mechanisms of aflatoxin carcinogenesis. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 34, 135–172 (1994).

- Wild, C. P. & Gong, Y. Y. Mycotoxins and human disease: a largely ignored global health issue. Carcinogenesis 31, 71–82 (2010).

- Aflatoxin Impacts and Potential Solutions in Agriculture, Trade, and Health. (2013).

- Wapner, J. A Genetically Modified Corn Could Stop a Deadly Fungal Poison—if We Let It. Newsweek (2017). Available at: http://www.newsweek.com/gmo-corn-cancer-571136. (Accessed: 10th November 2017)

- Blakemore, E. Computer game could help fight food-related disease. Washington Post (2017). Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/you-can-try-to-destroy-a-killer-in-the-food-system-by-playing-a-computer-game/2017/10/27/ab2e8b32-b989-11e7-9e58-e6288544af98_story.html?utm_term=.1e012c3d16ba. (Accessed: 10th November 2017)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

I am studying this – thank you for this information.

World is mostly getting toxins from feed they consume. like they eat meat and take milk have high level of toxins. aflatoxin are highly dangerous. thanks for share the article, they completely effect the fertility of the animals and humans. in human they mostly cause gastrointestinal problems. i am a veterinarian by profession. corn grains properly processed should be used. i read complete article of yours. what is recommended level of aflatoxin in feed of animals? read my article regarding it https:// technovets.net/aflatoxin-contamination-in-feed-and-milk-technovets/