#184: The Family Pluteaceae

Pluteaceae species, such as this Pluteus cervinus, have free gills and a pink spore print. Photo by Stu’s Images [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Description

Pluteaceae fungi produce mushrooms with a circular pileus, a central stipe and free gills that radiate out from the stipe. The unifying feature of this group is the spore print color, which is some shade of pink. Spore color of the Pluteaceae can vary anywhere between orange-pink and brown-pink. The pluteaceae are primarily split up among two genera: Pluteus and Volvariella.1–3

Volvariella is fairly easy to differentiate from Pluteus. The former, as its name points out, contains mushrooms with a prominent volva. A volva is a sac-like membrane that surrounds the bottom of the stipe and is a remnant of the universal veil.2–4 Although Pluteus does not have a universal veil, a few species produce a partial veil that leaves a thin ring on its stipe.1,3,5,6 One unusual but helpful feature of Pluteus is that its stipe and pileus are easy to separate from one another.7

Most Pluteaceae mushrooms are saprobic, although at least one – V. surrecta – is parasitic on other mushrooms. Fungi in the genus Pluteus grow on rotting logs, so they always appear on or near wood. Some Pluteus specimens might fruit from the ground, but that is usually because the wood the fungus is decomposing is buried underground.3 Volvarella species decompose many types of forest litter and can be found fruiting from wood or the ground.2

Identifying to species

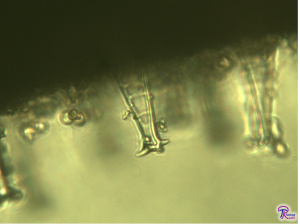

Cystidia are often important for identifying Pluteus species. In this photo of P. cervinus, the cystidium is the large cell in the center.

Identifying Pluteaceae mushrooms down to species ranges from easy to practically impossible. Some of the larger and distinctive mushrooms key out readily in field guides, but the genus also includes many smallish mushrooms with brownish caps. These often require microscopic analysis before you can label them with confidence. For mushrooms in the genus Pluteus, pay particular attention to the shape of the cystidia and the shape of the cells that make up the pileus’ top layer.5 In some cases, it may not be possible to assign a name to your collection. DNA studies have revealed that some species as they appear in field guides – such as P. cervinus, the Fawn Mushroom (FFF#142) – are actually species groups that contain cryptic species. There are no (or very few) features that differentiate the species in a species group from one another, so DNA analysis is the only way to decide which species it is.1

Edibility

The Pluteaceae contain edible, boring, and poisonous/ hallucinogenic mushrooms. The two most widely eaten mushrooms in the group are P. cervinus and V. volvacea (the Paddy Straw Mushroom, which is a staple of Asian restaurants). V. volvacea can be easily confused with the deadly Amanita virosa (FFF#050), so always remember to thoroughly check your mushrooms before eating them. Most of the mushrooms in the group are not poisonous but also not worth eating due to their small size or unpleasant taste. A few mushrooms in the group, such as P. salicinus, are known to contain psychoactive toxins.3

Similar species

Volvariella species, such as this V. bombycina, are distinguished by their prominent volva found at the base of the stipe. Thanks to the volva, these mushrooms can be confused with Amanita species. Photo by Angelos Papadimitriou (Aggelos(Xanthi)) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Volvariella species can also cause some confusion with Amanita (FFF#172) mushrooms, especially when young. Spore color is the easiest way to separate the two genera: Volvariella spores are pink while Amanita spores are white. However, the pigmented spores are sometimes difficult to see in young Volvariella specimens. In order to be sure that you haven’t collected an Amanita, simply take a spore print. Additionally, many (but not all!) Amanita species have a ring.2

Taxonomy

Mycologists have yet to study this family’s genetic relationships in great detail, but the preliminary results do not look good for the family as I described it above. Traditionally, the Pluteaceae include mushrooms in Pluteus, Volvariella, and a few other morphologically similar genera. Recent DNA studies largely backed up the traditional view of Pluteus. Unfortunately, they also suggested that Volvariella is polyphyletic. The main group of mushrooms in that genus appears to be more closely related to waxy caps (FFF#182). However, this has not yet been finalized and the genus remains in Pluteaceae for the moment.2,5,8

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Division | Basidiomycota |

| Subdivision | Agaricomycotina |

| Class | Agaricomycetes |

| Subclass | Agaricomycetidae |

| Order | Agaricales |

| Family | Pluteaceae Kotl. & Pouzar9 |

This post describes a group of mushrooms and as such the information on this page (including the pictures) cannot be used to identify any mushroom in particular.

This post does not contain enough information to positively identify any mushroom. When collecting for the table, always use a local field guide to identify your mushrooms down to species. If you need a quality, free field guide to North American mushrooms, I recommend Michael Kuo’s MushroomExpert.com. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out!

See Further:

http://www.mushroomexpert.com/pluteus.html

http://www.mushroomexpert.com/volvariella.html

Citations

- Kuo, M. The Genus Pluteus. MushroomExpert.Com (2015). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/pluteus.html. (Accessed: 7th April 2017)

- Kuo, M. The Genus Volvariella. MushroomExpert.Com (2011). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/volvariella.html. (Accessed: 7th April 2017)

- Miller, O. K. & Miller, H. North American mushrooms: a field guide to edible and inedible fungi. (Falcon Guide, 2006).

- Butler, E. Trial field key to the species of Volvariella in the Pacific Northwest. Pacific Northwest Key Council (2012). Available at: http://www.svims.ca/council/Volvar.htm. (Accessed: 7th April 2017)

- Iliffe, R. Getting to Grips with Pluteus. Field Mycology 11, 78–92 (2010).

- Justo, A. et al. Phylogeny of the Pluteaceae (Agaricales, Basidiomycota): taxonomy and character evolution. Fungal Biol 115, 1–20 (2011).

- Ramsey, R. W. Trial field key to the species of ENTOLOMATACEAE in the Pacific Northwest. Pacific Northwest Key Council (2003). Available at: http://www.svims.ca/council/Entolo.htm. (Accessed: 31st March 2017)

- Volvariella. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?TableKey=14682616000000067&Rec=57616&Fields=All. (Accessed: 7th April 2017)

- Pluteaceae. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?TableKey=14682616000000067&Rec=93034&Fields=All. (Accessed: 7th April 2017)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

3 Responses

[…] taxa contain mushrooms that produce pink spores. The most notable of these is the genus Pluteus (FFF#184), which can be distinguished by its free gills and its stipe that easily separates from the pileus. […]

[…] Pluteaceae31,32 […]

[…] cervinus and other mushrooms in the group are distinctive characteristics of the family Pluteaceae (FFF#184). Despite the fact that P. cervinus is being split into multiple species, the mushroom’s higher […]