#183: The Family Entolomataceae

Species in the Entolomataceae, such as this Entoloma vernum, have attached gills, a pink spore print, and angular spores. Although the gills may appear free in this picture, they are still attached by notch at the top of the stipe. Photo by Dan Molter (shroomydan) at Mushroom Observer [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Description

Entolomataceae mushrooms are very diverse morphologically, even within the genera, so it is impossible in this post to describe all the forms they take with any degree of precision. Visit the links at the bottom of this post if you want to learn more about the morphology of specific groups within the Entolomataceae.

Most Entolomataceae are umbrella-like, with a circular pileus, a centrally located stipe, and gills that radiate out from the stipe. However, some species have an off-center stipe or are pleurotoid (see FFF#180).1,2

These mushrooms produce gills that are attached, although this is sometimes difficult to verify. In many species, the gills are attached with a deep notch, so they may look like they do not touch the stipe. Other species have gills that break off of the stipe at maturity. In both cases, careful examination of the top of the stipe will reveal vertical lines where the gills attach(ed) to the stipe.1

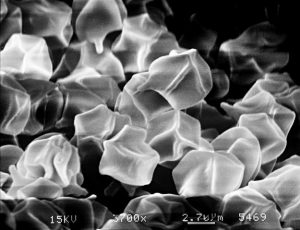

Entoloma sp. spores displaying the ridges and pits characteristic of the Entolomataceae. Photo by Alan Rockefeller at Mushroom Observer [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

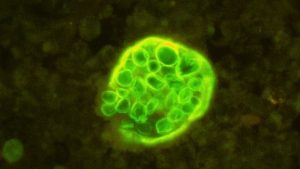

Spore morphology can also be used to distinguish genera within the Entolomataceae. The genus Entoloma features spores with distinct ridges and pits. In most species, the ridges are completely connected. Certain species, however, produce ridges that sometimes don’t connect on one end. Other Entoloma species have these incomplete ridges but also feature small bumps scattered over the spore surface. Spores of the genus Clitopilus appear lined along the long axis when viewed from the side. These lines are actually grooves, so the spores appear angular when viewed from the end. The least angular spores are produced by the genus Rhodocybe. Instead of regular ridges or grooves, Rhodocybe spores grow distinct bumps. This still ends up looking somewhat angular when viewed on end.1,3

Most Entolomataceae fungi are saprobic and they primarily decompose leaves, twigs, and other forest litter. As a result, you usually find these mushrooms growing on the forest floor. Of course, there are exceptions to these general rules. The pleurotoid mushrooms in the family appear instead on wood or other mushrooms. Actually, a surprising number of Entolomataceae mushrooms are mycotrophic, meaning they parasitically attack other mushrooms instead of decomposing plant material.1

Identifying to Species

Clitopilus sp. spores displaying faint longitudinal ridges. Photo by Ron Pastorino (Ronpast) at Mushroom Observer [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Edibility

There are a few edible species in the Entolomataceae, but most are inedible or poisonous. Given how difficult it is to identify mushrooms in this group to species, it is probably wise to avoid the group entirely. You won’t be missing much.4

Similar Species

The pink spores of this Entoloma sp. are clearly visible on its stipe. Mushrooms with pink spores from other lineages do not have angular spores.

Numerous other taxa contain mushrooms that produce pink spores. The most notable of these is the genus Pluteus (FFF#184), which can be distinguished by its free gills and its stipe that easily separates from the pileus. Most look-alikes have at least one of the following features: free gills, a ring on the stipe, a cobweb-like partial veil (‘cortina’), or a stipe that readily breaks away from the pileus. No Entolomataceae mushrooms have any of those features. The easiest way to eliminate the remaining similar species is to check for the presence of angular spores. Only the Entolomataceae have angular spores and all Entolomataceae mushrooms have some version of angular spores.1

Taxonomy

The Entolomataceae is one of the rare groups of fungi that the DNA era left relatively unscathed. DNA evidence from 2009 demonstrated that the family was monophyletic, so the group remains taxonomically relevant today. The genus Entoloma underwent the biggest change. Contrary to the general trend in fungal systematics, mycologists found that Entoloma should include a greater number of species. Prior to genetic assessment, mycologists had split Entoloma into numerous smaller genera based on morphology. However, DNA analysis demonstrated that Entoloma was indeed a large and morphologically diverse genus; many smaller genera were therefore reabsorbed into Entoloma.3

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Division | Basidiomycota |

| Subdivision | Agaricomycotina |

| Class | Agaricomycetes |

| Subclass | Agaricomycetidae |

| Order | Agaricales |

| Family | Entolomataceae Kotl. & Pouzar5 |

This post describes a group of mushrooms and as such the information on this page (including the pictures) cannot be used to identify any mushroom in particular.

This post does not contain enough information to positively identify any mushroom. When collecting for the table, always use a local field guide to identify your mushrooms down to species. If you need a quality, free field guide to North American mushrooms, I recommend Michael Kuo’s MushroomExpert.com. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out!

Citations

- Ramsey, R. W. ENTOLOMATACEAE in the Pacific Northwest. Pacific Northwest Key Council (2003). Available at: http://www.svims.ca/council/Entolo.htm. (Accessed: 31st March 2017)

- Kuo, M. Entolomatoid Mushrooms. MushroomExpert.Com (2013). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/entoloma.html. (Accessed: 31st March 2017)

- Co-David, D., Langeveld, D. & Noordeloos, M. E. Molecular phylogeny and spore evolution of Entolomataceae. Persoonia 23, 147–176 (2009).

- Miller, O. K. & Miller, H. North American mushrooms: a field guide to edible and inedible fungi. (Falcon Guide, 2006).

- Entolomataceae. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?TableKey=14682616000000067&Rec=92808&Fields=All. (Accessed: 31st March 2017)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

3 Responses

[…] pink-spored mushrooms. The most notable of these are mushrooms in the family Entolomataceae (FFF#183). In theory, Entolomataceae mushrooms are easy to separate because they have attached gills, lack a […]

[…] Entolomataceae33,34 […]

[…] that are angular under the microscope, gills that attach to the stipe, and terrestrial habitat (see FFF#183 for more on Entoloma). Aside from the presence of aborted mushrooms, there are scant distinctive […]