#223: Lepista nuda, The Blewit

Lepista nuda, commonly known as the Blewit, is a lovely shade of light purple when young. Unfortunately, it quickly fades to tan, making it difficult to ID.

Lepista nuda, often called Clitocybe nuda, is a popular edible mushroom known as the “Bewit” or “Wood Blewit.” I’ve put off writing about these mushrooms for a long time because they’re one of the most difficult edible mushrooms to positively identify. Until this fall, I wasn’t completely sure of my ability to identify these mushrooms. The problem is that Blewits have very few unique characteristics and can therefore be confused with many poisonous mushrooms. Blewits are definitely not beginner mushrooms. Young Blewits are a beautiful lilac color and can be confused with Cortinarius. With age, Blewits become tan and can be confused with Cortinarius, other clitocybioid mushrooms, and probably others as well. With so many possible lookalikes, remember: “When in doubt, throw it out!”1

Description

Lepista nuda is a normal-looking mushroom: it has a circular pileus with gills underneath and a central stipe. Actually, it looks a lot like your typical grocery store mushroom (Agaricus bisporus, FFF#002). The most distinctive feature of L. nuda is its color – all surfaces are tinted purplish when young. However, that color quickly fades and the mushroom matures to become a medium-sized to large tan mushroom.1–5

Young Blewits are easy to recognize (after you take a spore print) thanks to their color, habitat, and affinity for colder weather.

The Blewit features a circular cap that is light purple (lilac to light bluish-purple) when young but rapidly changes to a dark to pale tan. This makes Blewits difficult to spot in the woods – they are about the same color as fallen leaves. When young, the cap is circular and lightly domed and the margin is rolled underneath the cap slightly. As the mushroom grows, the pileus and margin flatten out. The cap often becomes slightly lobed or wavy, especially near the edges. When fully grown, the pileus typically reaches 4-20cm across. This is usually larger than the mushroom’s height, making the Blewit a stocky mushroom.2–5

Underneath the pileus, the mushroom has gills that radiate out from the central stipe. As with the cap, L. nuda’s gills start out purplish and fade to tan with age. The gills usually have a nice S-shape curve to them, growing deeper near the center and shallower near the cap margin. Where the meet the stipe, the gills attach directly near the top of the stipe – often with a small notch – or run down the stipe a bit (“short-decurrent”). The gills deposit a pinkish white spore print, which helps separate L. nuda from many similar mushrooms.2–5

L. nuda‘s spores are pale and have a pinkish tinge. The pinkish color can be difficult to assess unless you have a white paper to reference.

The Blewit’s stipe is light purplish when young and fades to tan in short order, just like the rest of the mushroom. When fully grown, the stipe is 3-10cm long, which is usually shorter than the width of the cap.2–5 The stipe is relatively thick for a mushroom of the Blewit’s size, growing 1-3cm thick where it meets the gills (this is similar in thickness to Agaricus bisporus).2–6 The stipe can remain roughly the same thickness throughout its length, but more often flares out at the base to end in a distinct bulb. This bulb usually includes embedded debris from whatever the mushroom was growing in and is coated in tiny fibers that are pale purplish to whitish.2–5 The mushroom’s interior is soft and purplish to whitish with a pleasant but not distinctive odor and taste (sometimes the taste is bitter).2,4

Ecology

Blewits, like other Clitocybe relatives, are litter decomposers. They eat their way through just about anything that trees drop. Large piles of leaves or mulch from either broadleaves or conifers seem to be particularly attractive to Blewits, though they also appear in other organic-rich habitats like compost piles.2–5 When you find some, try throwing a few of the mushrooms on your mulch or compost – you might get lucky and have some Blewits growing right next to your house the following year!7 These mushrooms sometimes grow in fairy rings, so if you find one, look around to see if there are any more nearby.3,4

Blewits most often appear in the fall, although their season ranges from late summer to early winter.2–5 Sometimes the mushrooms fruit outside their normal season, so it’s possible (but not likely) to find them at other times.3,4 Because of the season, L. nuda usually fruits from underneath recently deposited leaves, so you’re not likely to see the mushrooms until they’re old enough to push the leaves up a bit. I’ve had the best luck spotting Blewits on slopes, where there aren’t as many leaves and where small disturbances in the leaf layer are easy to notice. L. nuda is common all across North America and Europe.2,4 There are some reports of the mushrooms on all other continents as well, so the Blewit might be a truly global species.8,9Similar Species

There are lots of other mushrooms that grow on the ground with a central stipe, attached gills, and purplish or tan colors.3,5 Because of the sheer number of lookalikes, Blewits are not well suited for beginner foragers. The most problematic of these are species of Cortinarius (see FFF#186). Cortinarius mushrooms tend to have a similar shape and stature to Blewits and there are many that feature purple colors.1,3–5 In my area, Cortinarius iodes with its blue-purple colors is probably the mushroom that overeager foragers are most likely to mistake for the Blewit. Unfortunately, most Cortinarius species are toxic and many contain the potentially deadly toxin orellanine (see FFF#093).1

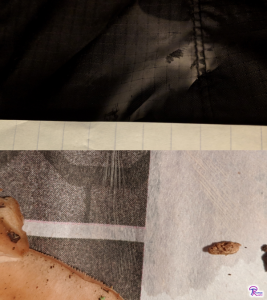

Old Blewits lose all of their purple colors and can grow to large sizes. This one is about medium-sized for Blewits.

Differentiating Cortinarius from L. nuda is a fairly simple matter of taking a spore print: Cortinarius spores are rusty-brown, very different from the Blewit’s pale spores.1,3–5,10 Before you get home and do a spore print, there are some field characteristics you can use to help you rule out all but the most confusing Cortinarius specimens. Cortinarius species have cobwebby partial veils (“cortinas”) that disappear fairly quickly.1,10 If you find a cobwebby veil on a young mushroom, it’s definitely not a Blewit since Blewits have no veil of any kind.3 Even after the veil disappears, it can leave some invisible fibers on the stipe that catch some of the falling spores.10 This sometimes results in brownish streaks that run down the stipe and rub off easily, which tells you the mushroom has a brown spore print and a cobwebby veil – absolutely something to avoid. Finally, Cortinarius is a mycorrhizal genus.10 This means it always fruits from the ground and not on tree litter.10 Since Blewits grow on debris from trees, they often incorporate some of that debris (such as twigs and leaves) into the base of their stipe. Cortinarius mushrooms rarely do this, although it can happen. If you find a troop of Blewit-like mushrooms that all have debris in their bases, they are probably not Cortinarius mushrooms (they could still be something else, however).

Clitocyboid mushrooms – species of Clitocybe and other close relatives of Lepista nuda – are another major source of confusion.1,11 Although not deadly, they can still cause uncomfortable symptoms including cramps, sweating, elevated heart rate, salivation, and crying. These mushrooms are all very similar because they are all related. Purple colors are rare in this group, so young Blewits are easy to distinguish.1 When Blewits turn tan, things get a little more difficult. A good local field guide is your friend here – use the guide to check for possible sources of confusion. Most clitocyboid mushrooms have gills that are attached to or begin to run down the stipe, while the Blewit’s gills are more often attached with a notch (of course, there is overlap in this feature).11 The tan Blewits that I’ve found seem to be a little less sure of their colors than most other clitocyboid mushrooms: the shades of tan on their caps tend to be subtly varied and patchy, especially near the margin. Unfortunately, this is not a good distinguishing factor. The best way to learn how to tell Blewits apart from other clitocyboid mushrooms is to go out and find some Blewits (preferably with someone who knows how to ID them). The more you find L. nuda, the more you’ll get a sense of what it should and shouldn’t look like.

Some species of Laccaria – such as Laccaria ochropurpurea, which is common in my area – are also similar to Blewits. Laccaria species tend to have purple gills, but their other surfaces are more likely to be whitish or brownish. The gills are thick, well-spaced, and remain purplish throughout development and the stipe is distinctly fibrous, making it easy to distinguish Laccaria from the Blewit.3,12 Fortunately, Laccaria mushrooms are mostly harmless and many are edible.13 North America has a few other purple agarics (both poisonous ones and edible ones), but these tend to be much smaller and/or have darker spore prints than L. nuda.3

Remember, “When in doubt, throw it out!” Seriously. I picked some tan-colored ones the other day that were just a little thinner and taller than I expected, so I threw them out. Were they Blewits? Probably, but I couldn’t be sure and didn’t want to risk eating something else.

Edibility and Uses

Blewits are edible mushrooms and many consider them choice. However, you should never eat Blewits raw because they will cause gastrointestinal upset. They must be thoroughly cooked to destroy the toxins. Even then – as with any mushroom – a few people have a sensitivity to these mushrooms. When you first eat this mushroom, just try a little bit to know how you will react (this is good advice for every new mushroom you try).3–5

One problem with Blewits is that their flavor is a little inconsistent. Young mushrooms have the best flavor (and color) and certain patches are more flavorful than others.3,7 How do you find the best patches? You’ll have to go out and try ones from as many different areas as possible. Blewits have a mild flavor reminiscent of grocery store mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) but with a bit more… something… The flavor’s a little hard to describe but is pleasant. Because of its rather delicate flavor, the mushroom is best served by itself (fry it up without much seasoning or cook it in a cream sauce) or with less flavorful dishes like rice, pasta, chicken, or pork.4,14 The Blewit’s texture is also similar to familiar grocery store mushrooms, which makes it a very accessible wild mushroom for the taste buds.

If you don’t like eating mushrooms, there is another use for Blewits: dyeing wool. When used with an iron mordant, they will impart a light green dye to wool.4,5

Taxonomy

The exact name of Lepista nuda is still under debate. Most sources you find will probably use the name Clitocybe nuda. The “lumpers” would prefer to keep the Blewit in Clitocybe, which contains mushrooms that are very similar but have a pure white spore print. Their opponents the “splitters” suggest that spore print color is different enough to move it into a different genus.1,11 Currently, the splitters are winning since Lepista nuda is the accepted name in Mycobank.15 As with many mushroom names these days, don’t be surprised if a DNA study changes its placement in the future.

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Subkingdom | Dikarya |

| Division | Basidiomycota |

| Subdivision | Agaricomycotina |

| Class | Agaricomycetes |

| Subclass | Agaricomycetidae |

| Order | Agaricales |

| Family | Tricholomataceae |

| Genus | Lepista |

| Species | Lepista nuda (Bull.) Cooke15 |

This post is not part of a key and therefore does not contain enough information to positively identify any mushroom. When collecting for the table, always use a local field guide to identify your mushrooms down to species. If you need a quality, free field guide to North American mushrooms, I recommend Michael Kuo’s MushroomExpert.com. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out!

See Further:

https://www.mushroomexpert.com/clitocybe_nuda.html

http://www.mykoweb.com/CAF/species/Clitocybe_nuda.html

https://www.first-nature.com/fungi/lepista-nuda.php

http://mushroom-collecting.com/mushroomblewits.html

https://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/nov98.html

Citations

- Volk, T. J. Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for November 1998. Tom Volk’s Fungi (1998). Available at: https://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/nov98.html. (Accessed: 23rd November 2018)

- Kuo, M. Clitocybe nuda. MushroomExpert.Com (2010). Available at: https://www.mushroomexpert.com/clitocybe_nuda.html. (Accessed: 23rd November 2018)

- Wood, M. & Stevens, F. California Fungi—Clitocybe nuda. California Fungi Available at: http://www.mykoweb.com/CAF/species/Clitocybe_nuda.html. (Accessed: 23rd November 2018)

- O’Reilly, P. Lepista nuda (Bull.) Cooke – Wood Blewit. First-Nature Available at: https://www.first-nature.com/fungi/lepista-nuda.php. (Accessed: 23rd November 2018)

- Spahr, D. Blewits (Lepista nuda, Clitocybe nuda). Mushroom-Collecting.com Available at: http://mushroom-collecting.com/mushroomblewits.html. (Accessed: 23rd November 2018)

- Kuo, M. Agaricus bisporus. MushroomExpert.Com (2018). Available at: https://www.mushroomexpert.com/agaricus_bisporus.html. (Accessed: 29th November 2018)

- Bergo, A. Blewits. Forager Chef (2018). Available at: https://foragerchef.com/blewits/. (Accessed: 23rd November 2018)

- Occurrence Map for Lepista nuda (Bull.) Cooke. Mushroom Observer Available at: https://mushroomobserver.org/name/map/182. (Accessed: 23rd November 2018)

- Blewit (Lepista nuda). iNaturalist Available at: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/351380-Lepista-nuda. (Accessed: 23rd November 2018)

- Kuo, M. The Genus Cortinarius. MushroomExpert.Com (2011). Available at: https://www.mushroomexpert.com/cortinarius.html. (Accessed: 1st December 2018)

- Kuo, M. Clitocyboid Mushrooms. MushroomExpert.Com (2008). Available at: https://www.mushroomexpert.com/clitocyboid.html. (Accessed: 1st December 2018)

- Kuo, M. The Genus Laccaria. MushroomExpert.Com (2010). Available at: https://www.mushroomexpert.com/laccaria.html. (Accessed: 30th November 2018)

- Miller, O. K. & Miller, H. North American mushrooms: a field guide to edible and inedible fungi. (Falcon Guide, 2006).

- Bergo, A. Blewits sauteed with shallots and tarragon. Forager Chef (2015). Available at: https://foragerchef.com/sauteed-blewits-shallots-and-tarragon/. (Accessed: 23rd November 2018)

- Lepista nuda. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?TableKey=14682616000000067&Rec=14261&Fields=All. (Accessed: 23rd November 2018)

![#070: Ganoderma applanatum, The Artist’s Conk [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-medium-empty.png)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)