#222: Cryphonectria parasitica, Chestnut Blight

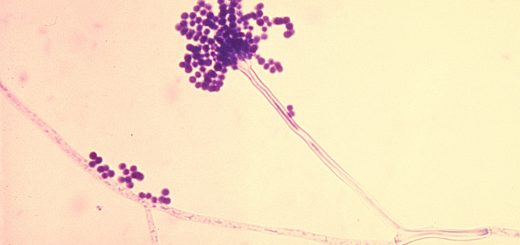

American Chestnut trees once dominated the forests of eastern North America, but they were quickly decimated in the mid-20th century by Chestnut Blight (caused by the fungus Cryphonectria parasitica). Spores of the fungus are visible as orange powder in the picture above.

The American Chestnut Tree, Castanea dentata, was once one of the dominant trees in eastern North American forests. It rivalled oak trees in terms of size and abundance. The trees were also highly valued for their rot-resistant wood and edible seeds, making it one of the most economically important trees in eastern North America. So, if the trees were so common and so important, where are they today? The downfall of the American Chestnut began in New York in 1904, when a disease called Chestnut Blight suddenly appeared and swept across the continent. By 1950, the disease had infected and killed almost every American Chestnut. Chestnut Blight is caused by the Asian fungus Cryphonectria parasitica, which grows in the outer wood of the tree and essentially chokes trees to death. The aggressive pathogen has doomed the American Chestnut to extinction, unless humans can come up with a solution.1,2

The American Chestnut

The American Chestnut was once one of the most populous trees in eastern North American forests, with over 3.5 billion trees growing from Maine to Mississippi in a wide swath centered around the Appalachian Mountains.3 Each tree could grow 50-75ft in height, although particularly big trees could reach heights of over 100ft.4,5 Mature trees had a more or less spherical crown of branches, making it a decent shade tree.4

Wood from the tall and straight American Chestnut was straight-grained and exceptionally resistant to rot. This made the wood highly valued for use in places susceptible to rot.1,6 Chestnut wood was used in log cabins (especially as foundation logs), building frames, fences, railroad ties, flooring, furniture, and even musical instruments.1,2,6

Chestnut trees produce seeds covered in large spiky husks. These husks were probably from a Chinese or hybrid chestnut tree planted in someone’s yard (squirrels probably carried the husks away, so I couldn’t find the tree that produced them to confirm its ID).

Chestnut seeds were perhaps even more valuable than the lumber. American Chestnut trees flowered in the late spring (at about the same time as Black Locust trees) and produced nuts in the early fall.5,7 The flowers were produced on catkins – long drooping stems that resembled pipe cleaners when in bloom.5,7 Male flowers were pale green to white, produced a pleasant aroma, and took up most of the space on the catkin. Female flowers were inconspicuous and could be found just at the base of the catkin.5 A few months later, the female flowers developed into large (2-2.5in) spiky husks called burs that contained two or three nuts each and resembled green sea urchins. The nuts were 0.5in to 1in wide, chestnut-brown, shiny but covered by white hairs on the lower half, and shaped like a flattened onion: they were rounded with a flattened top and a pointed base and were oval to D-shaped in cross-section.5,8 Mature trees produced a few hundred pounds of edible nuts every year.9

Since it flowered so late, it avoided impacts from frost and could produce a consistent supply of nuts (this sets the chestnut apart from oak trees, which flower earlier and drop different amounts of acorns every year).1,2 This provided wildlife – including rodents, deer, bears, and turkeys – with a reliable supply of food.1 The nuts were also important food sources for humans; they could be cooked a variety of ways, from roasting to candying to steaming to milling for use as flour.1,9 Since chestnuts ripened in the fall they were commonly eaten during the winter months, which inspired the first line to “The Christmas Song.” Additionally, farmers used chestnut seeds to fatten up livestock before selling them.1

Tree Identification

It is easiest to identify the American Chestnut by its large serrated leaves. Its papery leaves are 5-8in long, oval, and taper to a point at both the tip and base. The edges of the leaf are distinctly serrated, which gives the American Chestnut its species name (dentata means “toothed”). On the upper surface, the leaf is dark green and lacks hairs; the underside is paler and also hairless.5,7,8

There are a few other chestnut trees – most of which have been imported from other continents – that look similar. The chinquapin is a close relative to the American Chestnut, so it looks very similar. It is smaller and has leaves with small teeth and hairs on the bottom.7 The chestnut tree you’re most likely to encounter is the Chinese Chestnut, which has oval-shaped leaves with a waxy texture and hairy underside.7,8 The Japanese Chestnut has leaves that are a bit more rectangular, have tiny teeth, and feature hairs on their underside. The European Chestnut produces leaves with a similar shape and texture to the American Chestnut but with a rounded tip and base.7 Any of these chestnut species can hybridize with the American Chestnut, so you can find trees with intermediate features and identification won’t be quite as easy as I’ve made it seem.7

Beech trees also have similar leaves, but their leaves are shorter and not nearly as long as American Chestnut leaves. If you’re still confused, look at the bark: beech trees have extremely smooth light grey bark that quickly distinguishes them. Horse Chestnut trees are another potential source of confusion, but they have “palmately compound” leaves composed of large leaflets that radiate out from a central point like spokes on a wheel.7

Cryphonectria parasitica

The causal agent of Chestnut Blight, Cryphonectria parasitica, is a fungus native to Asia. It naturally infects the Chinese and Japanese Chestnut trees and was probably introduced to North America with the import of ornamental Japanese Chestnut trees. In its native range, C. parasitica is a significant but not fatal disease because its host trees have defenses against the fungus.10–13

C. parasitica has a simple life cycle: infect a tree, then produce spores. The fungus first infects a tree when a spore lands on a wound in the tree’s bark. Once the spore germinates, it grows into the bark and nearby tissues (this is where most water and nutrient transport occurs). The tissues in this area will begin to die, resulting in an open wound called a “canker.”10–13 After only a month or two, the fungus is capable of producing spores.11 Most spore production happens from spring through fall, although C. parasitica will make spores whenever conditions are right.11

The first spores the fungus produces are asexual spores called “conidia.” C. parasitica makes small bright orange masses of tissue on the surface of the canker that are packed with spore-producing structures called “pycnidia.” Conidia ooze out of the pycnidia and can be picked up on the feet of passing insects, birds, or mammals, splashed into the air by raindrops, or blown into air currents by the wind.10–12

After a couple more months (or perhaps much longer), the fungus also starts to produce sexual spores called “ascospores.” These are produced in small blackish masses of tissue that contain flask-shaped structures called “perithecia.” The perithecia are lined with asci (sexual cells), which shoot the ascospores into the air.10,11 Sexual reproduction can happen only after the fungus contacts another sexual spore or compatible mycelium. The more spores there are floating around, the quicker the fungus can begin reproducing sexually.

Cankers from Chestnut Blight gradually get larger and encircle the branch, killing the tissues above the canker.

As the infection grows, the canker expands around the branch or stem, eventually completely cutting off the flow of nutrients above the canker. This causes the branch above the canker to die. C. parasitica will continue growing down the branch but will also grow up into the dead wood. In dead areas, the fungus can grow as a saprobe and continue producing spores for two years or longer. As the infection spreads – either by growth of the fungus or by spores colonizing new branches – larger and larger branches will be choked off until the entire tree has lost its leaves. This process may take years to complete in fully grown trees, but can happen within a single year in saplings.10,11,13

In the early 20th century, when Chestnut Blight was spreading across the continent, people tried various methods for containing the fungus. Diseased trees were cut back, controlled burns were initiated, chestnut trees in soon-to-be-infected areas were cut down, and infected trees were sprayed with chemicals. None of these methods were effective.12 There are a few reasons for this. One is that the fungus spreads through animal contact as well as through the air. Another reason is that C. parasitica can grow successfully over the entire range of the American Chestnut; there are no climactic conditions that benefit the tree more than the fungus. Additionally, C. parasitica also infects a variety of oak species (White, Live, Post, and Scarlet Oaks, to name a few), Shagbark Hickory, Staghorn Sumac, and Red Maple. With so many potential hosts, there is always wood around for the fungus to infect and continue its life cycle.13 This also means that even though the American Chestnut has largely vanished from the landscape, C. parasitica will always be around to infect any new chestnuts that are planted in the eastern United States.

The State of Chestnuts Today

Although Chestnut Blight killed all the American Chestnuts over 50 years ago, the American Chestnut is still growing in eastern forests today. American Chestnuts are able to grow new shoots from the root stock (“suckers”), so many trees killed by C. parasitica are still able to produce new trunks and leaves. Unfortunately, this new growth is genetically identical to the original tree that was killed by the fungus. So, the suckers succumb to Chestnut Blight soon after they sprout.10–12

Millions of chestnut trees are still alive today, repeatedly regrowing from their roots. They eke out an existence as understory trees, but rarely grow large enough to reproduce. The small tree in the center is the American Chestnut — it was already infected by Chestnut Blight in several places and will probably die back soon.

Occasionally, the suckers will live long enough to flower and produce seeds. However, you new two different trees for successful pollination. With so few mature trees, the chances of forming a viable seed are very slim. Once the seed forms, it faces other hazards. When the chestnut was a dominant forest tree, the large numbers of seeds it produced ensured that at least some of the seeds would avoid being eaten by wildlife. Today, the few seeds produced by a mature chestnut tree don’t have that same protection; a single squirrel could easily eat all of those seeds.10–12

As an example, there are 20 surviving American Chestnut trees in Rock Creek Park – the forested valley that cuts through the center of Washington, D.C. Of those trees (as of December 2017), half are under 5m in height, only three were over 20m tall, and all were shaded out by larger trees. None of these trees are capable of producing seeds. Currently, only two show symptoms of Chestnut Blight.14 This fairly small sample is emblematic of surviving American Chestnuts; they have been relegated to lower parts of the forest and manage to send up enough shoots to keep going but don’t have an opportunity to do much else before the blight cuts them back down to the ground.

Essentially, American Chestnut trees are at a genetic dead end. The surviving trees are merely copies of already doomed trees. This means the American Chestnut has ceased evolving and it’s only a matter of time (albeit a long time, thanks to its suckering abilities) before the tree goes extinct. [C. parasitica, on the other hand, is capable of producing sexual spores in a matter of months, allowing evolution to act very quickly on that species.] Without evolution, the American Chestnut also won’t be able to adapt to climate change, human activity, and whatever other pests or diseases globalization might throw its way.

Restoring the Forests

After the initial disaster ran its course, scientists began looking for ways to restore the American Chestnut to eastern forests. The most obvious way was to use selective breeding to introduce beneficial genes from the Chinese Chestnut – the most resistant species – into the defenseless American Chestnut. The process goes something like this. First, you pollinate a Chinese Chestnut with an American Chestnut. The resulting cross is a hybrid of the two species and will be partially resistant to the blight. You then take the hybrid and cross it with an American Chestnut. The offspring from that cross are screened for resistance and the most resistant ones are crossed with American Chestnut again. This process continues until only a very small percentage of key Chinese Chestnut genes remain in the hybrid. The result would be an American Chestnut with added blight tolerance. Of course, this process will take a very long time because you need to wait for each generation to produce seeds before beginning the next round of crosses.11,12 The project has not yet produced a viable replacement for the American Chestnut; the current estimate is that this work will be completed by 2022.15

An interesting control possibility was discovered when scientists found a population of C. parasitica in Europe that was growing unusually slowly in infected trees, allowing them to survive easily. After a few tests, they realized that this particular strain could fuse with other strains and infect them with its decreased aggressiveness or “hypovirulence.” Further research revealed that hypovirulence was due to a fungal virus (“mycovirus”). To save a tree using a hypovirulent strain, all you have to do is take a piece of the hypovirulent strain and put it on a canker. The hyphae of the hypovirulent fungus will fuse with those of the fungus in the tree and transfer the virus. This will cause the canker’s growth to slow and might save the tree.12,16,17

Hypovirulence proved effective at controlling Chestnut Blight in Europe (the European Chestnut is susceptible to Chestnut Blight, but doesn’t suffer as much as its American counterpart). However, the strategy has not worked well in America. The American strains of C. parasitica have a high number of “vegetative compatibility groups.” Fungal hyphae can fuse only if both fungi belong to the same vegetative compatibility group. In America, if you picked two fungi at random, you would have a roughly 1/6 chance of both being in the same vegetative compatibility group. European C. parasitica has fewer vegetative compatibility groups, so more fungi were able to fuse with one another and it was easier to spread hypovirulence. In America, there is too much genetic diversity within C. parasitica for hypovirulence to spread on its own. Consequently, hypovirulence can be used to save individual trees but cannot revive the American Chestnut population.12,16

Another complicating factor is that fungal viruses cannot spread through sexual spores. If it could, it would be able to cross boundaries between vegetative compatibility groups. To get around this problem, some research has been done attempting to insert the viral DNA into the fungus’ genetic code, which would transmit the virus through ascospores.12

Recently, another option has been added: genetic modification. In this scheme, a gene that naturally occurs in wheat would be added to the American Chestnut’s genome. The gene in question contains the instructions for oxalate oxidase, an enzyme that breaks down oxalic acid, a key chemical that C. parasitica uses in its attack. In 2014, the researchers produced a resistant tree that could pass its resistance on to its offspring. The researchers are now considering releasing it into the wild, but that process will take a long time. Since the tree is genetically modified, its use must be approved by the U.S. government. Various agencies will have to go through the lengthy process of assessing ethical issues, determining any potential threats to the ecosystem, deciding if and how to regulate the genes involved, determining whether the nuts are safe to eat, etc.9,18

Supporting Living Trees

What if you have a chestnut tree you want to save from Chestnut Blight? Unfortunately, there’s not much you can do. The best thing you can do is ensure your tree is living in optimal growing conditions. Make sure it gets plenty of sunlight, water, etc. to reduce stress and make infection less likely.13 If your tree is already infected, you can try cutting off the infected branches to prevent the spread of the fungus. You can also place soft clay on the cankers to keep other things out of the wounds and prevent the wood from drying out too much.11 None of these strategies will save the tree; you will probably have to cut it down and replace it with a resistant variety at some point.11,13

Taxonomy

Chestnut trees belong to the family Fagaceae, which also contains beeches and oaks. Most of the trees that can be infected by C. parasitica belong to this family as well.

C. parasitica is not closely related to any mushrooms I’ve talked about before. It belongs to the division Ascomycota and class Sordariomycetes. This means some of its distant relatives include Dead Man’s Fingers (FFF#005) and Cordyceps militaris (FFF#058). Most fungi in this group – including C. parasitica – produce sexual spores inside perithecia.

| Common Name | American Chestnut | Chestnut Blight Fungus |

| Kingdom | Plantae | Fungi |

| Subkingdom | Viridiplantae | Dikarya |

| Infrakingdom | Streptophyta | |

| Superdivision (Superphylum) | Embryophyta | |

| Division (Phylum) | Tracheophyta | Ascomycota |

| Subdivision (Subphylum) | Spermatophyta | Pezizomycotina |

| Class | Magnoliopsida | Sordariomycetes |

| Superorder | Rosanae | |

| Order | Fagales | Diaporthales |

| Family | Fagaceae | Valsaceae |

| Genus | Castanea | Cryphonectria |

| Species | Castanea dentata (Marsh.) Borkh.19 | Cryphonectria parasitica (Murrill) M. E. Barr20 |

This post is not part of a key and therefore does not contain enough information to positively identify any mushroom or plant. When collecting for the table, always use a local field guide to identify your mushrooms down to species. If you need a quality, free field guide to North American mushrooms, I recommend Michael Kuo’s MushroomExpert.com. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out!

See Further:

Cryphonectria parasitica

https://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/may98.html

https://forestpathology.org/canker/chestnut-blight/

http://plantclinic.cornell.edu/factsheets/chestnutblight.pdf (PDF)

https://www.esf.edu/chestnut/background.htm

Castanea dentata

https://www.acf.org/ky/american-chestnuts-kentucky/identifying-chestnut-tree/

https://www.acf.org/resources/identification/

http://dendro.cnre.vt.edu/dendrology/syllabus/factsheet.cfm?ID=21

News

Citations

- Background on American chestnut and chestnut blight. College of Environmental Science and Forestry Available at: https://www.esf.edu/chestnut/background.htm. (Accessed: 14th September 2018)

- The American Chestnut Tree. The American Chestnut Foundation Available at: https://www.acf.org/the-american-chestnut/. (Accessed: 14th September 2018)

- Rellou, J. Chestnut Blight Fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica). Introduced Species Summary Project (2002). Available at: http://www.columbia.edu/itc/cerc/danoff-burg/invasion_bio/inv_spp_summ/Cryphonectria_parasitica.htm. (Accessed: 14th September 2018)

- Castanea dentata. Missouri Botanical Garden Available at: http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?kempercode=a387. (Accessed: 14th September 2018)

- Seiler, J., Jensen, E., Niemiera, A. & Peterson, J. American chestnut: Fagaceae Castanea dentata (Marsh.) Borkh. Virginia Tech Dendrology Available at: http://dendro.cnre.vt.edu/dendrology/syllabus/factsheet.cfm?ID=21. (Accessed: 14th September 2018)

- History of the American Chestnut. The American Chestnut Foundation Available at: https://www.acf.org/the-american-chestnut/history-american-chestnut/. (Accessed: 14th September 2018)

- Identifying your Chestnut Tree. The American Chestnut Foundation Kentucky Available at: https://www.acf.org/ky/american-chestnuts-kentucky/identifying-chestnut-tree/. (Accessed: 14th September 2018)

- Chinese vs. American Chestnut (Castanea mollissima vs. Castanea dentata). The American Chestnut Foundation Available at: https://www.acf.org/resources/identification/chinese-american-chestnuts/. (Accessed: 14th September 2018)

- Haspel, T. Unearthed: Thanks to science, we may see the rebirth of the American chestnut. Washington Post (2014). Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/food/unearthed-thanks-to-science-we-may-see-the-rebirth-of-the-american-chestnut/2014/11/19/91554356-6b83-11e4-a31c-77759fc1eacc_story.html. (Accessed: 14th September 2018)

- Volk, T. J. Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for May 1998. Tom’s Volk’s Fungi (1998). Available at: https://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/may98.html. (Accessed: 15th September 2018)

- Conolly, N. B. Chestnut Blight: Cryphonectria parasitica. (2015).

- Anagnostakis, S. L. Revitalization of the Majestic Chestnut: Chestnut Blight Disease. American Phytopathological Society (2000). Available at: https://www.apsnet.org/pages/default.aspx. (Accessed: 15th September 2018)

- Chestnut Blight. Missouri Botanical Garden Available at: http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/gardens-gardening/your-garden/help-for-the-home-gardener/advice-tips-resources/pests-and-problems/diseases/cankers/chestnut-blight.aspx. (Accessed: 15th September 2018)

- American Chestnuts in Rock Creek (U.S. National Park Service). National Park Service (2018). Available at: https://www.nps.gov/articles/american-chestnuts-in-rock-creek.htm. (Accessed: 15th September 2018)

- Mulhollem, J. American chestnut rescue will succeed, but slower than expected | Penn State University. Penn State News (2017). Available at: https://news.psu.edu/story/468412/2017/05/16/research/american-chestnut-rescue-will-succeed-slower-expected. (Accessed: 15th September 2018)

- Worrall, J. J. Chestnut Blight. Forest Pathology Available at: https://forestpathology.org/canker/chestnut-blight/. (Accessed: 15th September 2018)

- Rigling, D. & Prospero, S. Cryphonectria parasitica, the causal agent of chestnut blight: invasion history, population biology and disease control. Mol. Plant Pathol. 19, 7–20 (2018).

- Popkin, G. To save iconic American chestnut, researchers plan introduction of genetically engineered tree into the wild. Science (2018). Available at: http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/08/save-iconic-american-chestnut-researchers-plan-introduction-genetically-engineered-tree. (Accessed: 15th September 2018)

- Castanea dentata (Marsh.) Borkh. Integrated Taxonomic Information System Available at: https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=19454#null. (Accessed: 15th September 2018)

- Cryphonectria parasitica. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/Biolomics.aspx?Table=Mycobank&Rec=7059&Fields=All. (Accessed: 15th September 2018)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

1 Response

[…] the mid-1900’s, Chestnut Blight (Cryphonectria parasitica, FFF#222) essentially wiped out all American Chestnut trees and dramatically altered the makeup of eastern […]