#198: Armillaria tabescens

The most distinctive features of Armillaria tabescens are its growth in dense clusters, its often terrestrial location, and its lack of a ring. This last feature earned it the common name “Ringless Honey Mushroom.”

Armillaria tabescens, the “Ringless Honey Mushroom,” is out in force in my area, a sure sign that summer is drawing to a close. Field guides often note that A. tabescens is the easiest honey mushroom to identify. That is true, but it relies on you accurately identifying it as a honey mushroom. Honey mushrooms (Armillaria spp.) are typically medium-sized to large agarics that grow in dense clusters, have a partial veil that leaves a ring, produce thick black rhizomorphs, and fruit from dead or dying wood. Of those features, the only one A. tabescens displays reliably is dense clustered growth. This makes it very difficult to identify if you’re unfamiliar with honey mushrooms. Fortunately, there are not many large mushrooms that grow in dense clusters, so it’s always worth checking the Armillaria section of your field guide when you find some.

Description

When you consider an A. tabescens mushroom on its own, it is not very distinctive. Each mushroom is brownish, umbrella-shaped, and grows 4-20cm tall and 3-10cm across.1–3 None of its features is particularly interesting; if I picked up a small A. tabescens mushroom growing on its own I’d probably toss it out as an annoying “LBM” (“Little Brown Mushroom,” of which there are too many to bother attempting an identification).

The pileus is circular and brown – ranging from yellowish to light brown to reddish-brown – often with a darker area over the center. When the mushroom is young, the pileus is convex and has an inrolled margin. As the mushroom matures, the cap flattens out and eventually develops a bowl-like depression over the center. The pileus is covered in tiny darker scales at first, but these fade away and by maturity there are usually just a few left over the center.1–3

Underneath the pileus, the mushroom’s gills radiate out from the central stipe. The gills are colored whitish to pinkish and run down the stipe slightly (“subdecurrent”). Spores dropped by the gills will leave a white spore print.1–3

On the stipe, you can find the mushroom’s most useful feature: it doesn’t have a ring. Most Armillaria species feature some kind of ring, but not the Ringless Honey Mushroom. Instead, the stipe of A. tabescens is smooth, although it may become fuzzy as it ages. The stipe is whitish near the top and darkens to brown near the base. Because the mushrooms grow in dense clusters, the stipe gets thinner as it nears the base and eventually fuses with its neighbors at the very bottom.1–3

Ecology

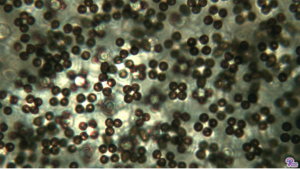

Perhaps more important for identification purposes than what A. tabescens mushrooms look like is how they grow. In particular, the Ringless Honey Mushroom’s tendency to grow in extremely dense clusters on the ground makes it instantly recognizable. Each cluster of mushrooms is usually composed of between 8 and 50 individual mushrooms whose stipes are so densely packed that they become fused together at the base (mycologists call this a “cespitose” or “caespitose” cluster).1–4 To fit so many mushrooms in the same space, the mushrooms grow out and away from one another and form a hemispherical mound, much like the way a bouquet of flowers fans out above the top of a vase. Once the mushrooms are fully grown, the cespitose clusters can easily reach sizes of 30cm or more.

The Ringless Honey Mushroom is a parasite and saprobe on the wood of hardwood trees. It seems to prefer for oaks, but can attack any type of hardwood tree.1,3 Unlike most other honey mushrooms, A. tabescens usually fruits terrestrially.1–3 The mushrooms can and do grow directly from tree stumps or right at the base of living trees, but I more often find them over 50cm from the host tree’s base and they may appear as far out as the outermost branches of the tree. Most mushrooms that fruit directly from the ground that far away from a tree are mycorrhizal. This is not the case with A. tabescens, so it is very easy to misinterpret the mushroom’s ecological role and rule out the honey mushrooms early on in the identification process (as I did when I first found this species). A. tabescens primarily attacks the roots of trees, which explains its unusual fruiting habit.1–3

Unlike most Armillaria species, the Ringless Honey Mushroom typically fruits from the ground. In places like this, the fungus is decomposing the wood found in tree roots.

Like other members of its genus, A. tabescens can form very large individuals (though it can’t compete with the absolutely enormous Humongous Fungus, A. solidipes, FFF#001). The last measurable A. tabescens individual I came across was roughly 72m long. Honey mushrooms are able to reach such remarkable sizes because they form structures called “rhizomorphs.” Rhizomorphs are thick bundles of mycelium that are visible to the unaided eye. In Armillaria, they are typically black and a few millimeters thick5 and branch and fuse just like hyphae do (see FFF#128), but on a much larger scale. The large size of the rhizomorphs makes the mycelium more efficient at transporting resources over long distances, which allows all parts of the fungus to stay connected even when the organism is very large. Although A. tabescens does form rhizomorphs, its rhizomorphs are rarely seen when collecting its mushrooms.1,6

A. tabescens appears in both North America and Europe (and likely elsewhere) and favors the more southerly regions of both continents.3 In North America, the Ringless Honey Mushroom is abundant in the southeastern United States but grows as far north as Michigan and as far west as Texas.1,4 In my area (northern Virginia), A. tabescens appears to be the dominant species of Armillaria in the suburbs. Right now, there seem to be Ringless Honey Mushrooms under at least one tree on every block. Other species of Armillaria are much rarer here and are mostly restricted to forested areas.

The Ringless Honey Mushroom appears very quickly in the late summer and early fall.1,2 I find it usually appears for only a couple of weeks, during which it produces 2-3 flushes of mushrooms. This is a fairly short time frame, but the mushrooms are extremely abundant during that period. In my region, A. tabescens reliably appears a week or two before the first fall mushrooms. This serves as a useful reminder to start looking for Grifola frondosa, a popular edible fall mushroom (see FFF#103).

Similar Species

Unsurprisingly, the mushrooms that most closely resemble A. tabescens are other members of the genus Armillaria. However, A. tabescens is easily distinguished from its relatives by its lack of a ring and lack of a partial veil at all stages of development.3–5

Aside from the color, the Jack-O-Lantern mushroom (Omphalotus illudens, FFF#007) is also very similar to A. tabescens. It is a large mushroom with decurrent gills that grows in cespitose clusters from the bases of dead trees. Fortunately, the Jack-O-Lantern is bright orange, so there is no way you can actually confuse it with the brown A. tabescens.

Once you know what to look for, A. tabescens is a fairly distinctive mushroom. However, you should still double check your collections to make sure you haven’t inadvertently picked up a Deadly Galerina. This is easiest to do when the Ringless Honey Mushroom is small, as in the picture above.

Mushrooms in the genus Pholiota also grow in cespitose clusters from wood. The most reliable way to separate them from A. tabescens is to take a spore print. Pholiota spores are brown, unlike the white spores of Armillaria. Additionally, Pholiota spp. have partial veils and the species that people most often find tend to be lighter in color and have larger and more distinctive scales than A. tabescens does.7

Of course, any time you’re collecting brownish fungi growing on wood for the table, you should be on the lookout for the Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata, FFF#124). You are unlikely to mistake this mushroom for a mature A. tabescens mushroom, but you could mistake it for a young A. tabescens if you’re not paying attention. G. marginata is a small to medium-sized brown mushroom that grows in clusters on dead wood. The biggest differences between G. marginata and A. tabescens are that G. marginata has a brown spore print and it has a ring.8

Edibility

Honey mushrooms are typically listed as edible.2,6 Mushroom hunters consider A. mellea the best of the honey mushrooms, so nobody gets very excited about A. tabescens. When trying honey mushrooms (or, indeed, any mushroom) for the first time, it is important to try only a little bit at first. Honey mushrooms are more likely to cause gastrointestinal irritation than most edible mushrooms, so don’t eat a lot of them until you know how your body reacts.3 These adverse reactions cause some authors to recommend against eating honey mushrooms, but other authors aren’t bothered by that and still consider the mushrooms “choice.”2,3 A. tabescens should be cooked thoroughly before you eat it to remove its slightly bitter taste.6 Doing so should also help minimize adverse reactions.

Taxonomy

A. tabescens belongs to the genus Armillaria, which contains a couple dozen ecologically and morphologically similar species. The genus used to include over 200 species, but most of those were excluded as mycologists refined the definition of the genus.5 The name “tabescens” translates to “decaying” or “wasting away,” presumably a reference to the mushroom’s role in decomposition.2,3

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Division (Phylum) | Basidiomycota |

| Subdivision (Subphylum) | Agaricomycotina |

| Class | Agaricomycetes |

| Subclass | Agaricomycetidae |

| Order | Agaricales |

| Family | Physalacriaceae |

| Genus | Armillaria |

| Species | Armillaria tabescens (Scop.) Emel9 |

This post does not contain enough information to positively identify any mushroom. When collecting for the table, always use a local field guide to identify your mushrooms down to species. If you need a quality, free field guide to North American mushrooms, I recommend Michael Kuo’s MushroomExpert.com. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out!

See Further:

http://www.mushroomexpert.com/armillaria_tabescens.html

http://www.messiah.edu/Oakes/fungi_on_wood/gilled%20fungi/species%20pages/Armillaria%20tabescens.htm

Citations

- Kuo, M. Armillaria tabescens. MushroomExpert.Com (2017). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/armillaria_tabescens.html. (Accessed: 8th September 2017)

- Emberger, G. Armillaria tabescens. Fungi on Wood (2008). Available at: http://www.messiah.edu/Oakes/fungi_on_wood/gilled%20fungi/species%20pages/Armillaria%20tabescens.htm. (Accessed: 8th September 2017)

- O’Reilly, P. Armillaria tabescens (Scop.) Emel – Ringless Honey Fungus. First Nature Available at: http://www.first-nature.com/fungi/armillaria-tabescens.php. (Accessed: 8th September 2017)

- Volk, T. J. Key to North American Armillaria species. Tom Volk’s Fungi Available at: http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/armkey.html#tab. (Accessed: 8th September 2017)

- Kuo, M. The genus Armillaria. MushroomExpert.Com (2017). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/armillaria.html. (Accessed: 8th September 2017)

- Miller, O. K. & Miller, H. North American mushrooms: a field guide to edible and inedible fungi. (Falcon Guide, 2006).

- Kuo, M. The Genus Pholiota. MushroomExpert.Com (2007). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/pholiota.html. (Accessed: 8th September 2017)

- Kuo, M. Galerina marginata. MushroomExpert.Com (2016). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/galerina_marginata.html. (Accessed: 8th September 2017)

- Armillaria tabescens. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/Biolomics.aspx?Table=Mycobank&Rec=1632&Fields=All. (Accessed: 8th September 2017)

![#013: Characteristics of Phylum Basidiomycota [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-medium-empty.png)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

Thank you for the post! It was very informative and timely.