#171: Reindeer Lichen

Reindeer Moss (Cladonia rangiferina) showing the thick main stalks. Public Domain photo via Wikimedia Commons

Reindeer Lichens grow in northern temperate forests, boreal forests, and even in the tundra. They are highly branched, fruticose lichens that are a primary food source for reindeer (also called caribou in North America). These lichens are sometimes called “Reindeer Moss,” even though they are lichens and not moss.1,2

Description

Reindeer Lichens, like other Cladonia species, form two types of structures. Initially, the lichen grows flat along the ground and produces small, scale-like protrusions (foliose morphology). Eventually, Reindeer Lichen develop upright, hollow, cylindrical, branching structures called podetia (fruticose morphology).1–3 Growth occurs at the edge of the basal, squamulose region and at the tips of the podetia. As the lichen gets bigger and forms a mat over the ground, resources like light and nutrients become less available to the center and base of the lichen. These areas die back and decompose while the outer edges continue growing.1 Consequently, the podetia of an old Reindeer Lichen do not necessarily connect to the squamulose base.

There are actually dozens species that go by the common name Reindeer Lichen.2 All of these look similar but can be separated by examining subtle morphological differences. However, you’ll probably need a lichenologist to accurately identify the lichens to species. The most common Reindeer Lichens in North America are Cladonia rangiferina, Cladonia arbuscula, Cladonia mitis, Cladonia stellaris, and Cladonia stygia.1 See the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Plant Profile for Reindeer Lichen for a more complete list of North American Reindeer Lichens.

Some species, such as C. rangiferina, produce podetia with a main stalk to which all the many branches connect. Others, such as C. stellaris, do not have a main stalk. Reindeer Lichens can also differ in the texture of the mat surface. For example, C. stellaris forms mats that are not flat but instead feature rounded bulges, somewhat like a carpet of tiny cumulus clouds. C. rangiferina, on the other hand, has a chaotic, bristly surface. Another common morphological difference is color. Reindeer Lichens are colored green to yellowish (e.g. C. mitis) to gray (C. rangiferina).5 The mats formed by Reindeer Lichens can be anywhere from 4cm to 12cm. C. rangiferina and C. stygia tend to form the tallest mats while C. stellaris forms the shortest.1

Ecology

Reindeer Moss growing in a large mat on the forest floor. Photo by Jason Hollinger [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The lichens described above are primarily northern species. They grow in northern temperate forests, boreal forests, and in the tundra, although different species prefer different areas.1 However, there are other North American Reindeer Lichens that grow as far south as the Gulf States. For example, the range of Cladina subtenuis extends from Newfoundland south to Florida and west to Nebraska and Oklahoma. The only areas in North America where Reindeer Lichens do not grow are the American Southwest and a couple Great Plains states.4

Reindeer Lichens can grow on a variety of substrates, including rocky expanses as well as the forest floor in both conifer and hardwood forests. Reindeer Lichens are generally latecomers to disturbed forests. They are most often found in old growth forests and forests that have not been burned or logged in at least 40 years. However, they are not tolerant of shade and as a result are most abundant in forests with sparse tree cover and in forest clearings.1

Mats formed by Reindeer Lichens are not simply a consequence of growth patterns. Rather, they also provide certain benefits to the lichen population. One such benefit is that it helps the lichen retain water. Even when the outer layer of the mat dries out, the spongy branches of the lichen underneath hold moisture for a long time. The lichens’ metabolism is closely tied to humidity, so this helps the lichen keep growing after the forest starts to dry out. Mats also limit the amounts of nutrients, water, and light available to other organisms, which prevent seeds from germinating. The few seeds that do germinate in the soil below the mat can be pulled out of the soil by the lichen as it expands and contracts due to changes in humidity.5 These last two actions prevent plants from colonizing the lichens’ area, which keeps the forest canopy open and allows the lichens access to sufficient amounts of sunlight.

Apothecia of Cladonia rangifera. Apothecia produce sexual spores but do not include the algal symbiont. Photo by Ed Uebel [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

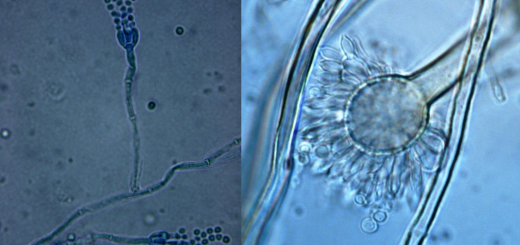

Reindeer Lichens do produce sexual spores in structures called apothecia that form at the tips of the podetia. However, the Trebouxia symbiont has not been found in nature and the sexual spores do not carry it with them. It is therefore unlikely that the sexual spores will be able to successfully form a new lichen.1

Reindeer

Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), also known as caribou in North America, have a large range that extends to the tundra all the way around the north pole. These animals are highly specialized for life in the arctic. If you want to read about the adaptations that allow reindeer to survive in such an extreme environment, see this page from the San Diego Zoo.*

The normal diet of a reindeer consists of ferns, grasses, mosses, and any other leaves or shoots they can find. However, these die back during the winter and are not available for the reindeer. When their primary sources of food become scarce, reindeer turn to their alternate food: Reindeer Lichen.7 Over the winter, reindeer rely on these and other lichens for roughly 90% of their food. C. stellaris is most commonly eaten species, followed by other Reindeer Lichens and finally other lichens.8 An adult reindeer has to eat 4 – 8kg of food a day, so they have to spend a lot of time looking for lichens.7 Reindeer Lichens are a good source of carbohydrates (which are extracted by special enzymes in the reindeers’ digestive system), but a poor source of protein. Even reindeer who eat their fill of lichens will lose weight by the end of the winter.5,6

Reindeer, also called caribou, rely on lichens for 90% of their diet during the winter. Photo by Alexandre Buisse (Nattfodd) [GFDL or CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Human activity is one of the main dangers to reindeer that rely on lichens for food. Lichens are very sensitive to pollution and can be killed by relatively low levels of common pollutants such as heavy metals and sulfur dioxide. This can cut the amount of food available to reindeer during the winter, especially around urban areas.2

Lichens also absorb radioactive materials, which was a problem for the area around Chernobyl after the 1986 meltdown. The lichens absorbed the radioactive atoms, which were eaten by reindeer and later found in reindeer meat and milk.2,9 Even 30 years after the incident at Chernobyl, reindeer meat from Norway is often deemed too radioactive for human consumption. In 2014, an exceptionally large amount of reindeer meat was thrown out because of radioactivity. Apparently that was due to excessive rain that year, which produced lots of mushrooms (which are also good at picking up radioactive atoms). Reindeer therefore ate more mushrooms and consumed more radiation than usual in 2014.9

Taxonomy

Mycologists have not quite decided where Reindeer Lichens should be classified. They are currently placed in the genus Cladonia, but some sources still classify them under Cladina (including the USDA’s PLANTS Database). More recent research suggests that Cladina is best used as a subgenus of Cladonia. The phylogenetic relationships within this group are far from settled, however. Don’t be surprised if the names change in the near future.1

Note the similarities in the taxon name endings for Reindeer Lichen and the green alga. This is due to the fact that fungi were once classified as plants. Even though the fungi received their own kingdom, mycologists still use the botanical endings for taxon names.

| Common Name | Reindeer Lichen | Reindeer (Caribou) | Trebouxia green alga |

| Kingdom | Fungi | Animalia | Plantae |

| Subkingdom | Bilateria | Viridiplantae | |

| Phylum | Ascomycota | Chordata | Chlorophyta |

| Subphylum | Pezizomycotina | Vertebrata | Chlorophytina |

| Class | Lecanoromycetes | Mammalia | Trebouxiophyceae |

| Subclass | Lecanoromycetidae | Theria | |

| Order | Lecanorales | Artiodactyla | Trebouxiales |

| Family | Cladoniaceae | Cervidae | Trebouxiaceae |

| Genus | Cladonia

Cladina |

Rangifer | Trebouxia Puymaly10 |

| Species | Cladonia rangiferina (L.) Weber ex F.H. Wigg.11

Cladonia arbuscula (Wallr.) Flot.12 Cladonia mitis Sandst.13 Cladonia stellaris (Opiz) Pouzar & Vezda14 Cladonia stygia (Fr.) Ruoss15 Cladina subtenuis (Abbayes) Hale & W.L. Culb.16 |

Rangifer tarandus (Linnaeus, 1758)17 |

* Side Note (not included on Zoo page): Arctic reindeer are one of the few animals to lack a circadian clock. Consequently, they do not have regular sleep-wake cycles during summer and winter, when it is constantly light or dark, respectively. See this scientific paper and this WIRED article for more information.

See Further:

https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/lichens/claspp/all.html

http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/dec2000.html

https://www.borealforest.org/lichens/lichen3.htm

http://hikersnotebook.net/Reindeer+Lichen (read this if you like learning etymology)

http://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/reindeer

http://www.rferl.org/fullinfographics/infographics/chernobyls-reindeer/27575578.html (radioactive reindeer visual article)

Citations

- Gregory T. Munger. Cladonia spp. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer) (2008). Available at: https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/lichens/claspp/all.html. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Thomas J. Volk. Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for December 2000. Tom Volk’s Fungi (2000). Available at: http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/dec2000.html. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Heino Lepp. Form and structure. Australian National Botanic Gardens (2011). Available at: http://www.anbg.gov.au/lichen/form-structure.html. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Plants Profile for Cladina (reindeer lichen). USDA PLANTS Database Available at: http://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=cladi3. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Cladina – Reindeer Lichens. borealforest.org Available at: https://www.borealforest.org/lichens/lichen3.htm. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- William Donald Needham. Reindeer Lichen. Hiker’s Notebook (2011). Available at: http://hikersnotebook.net/Reindeer+Lichen#discussion. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Reindeer. San Diego Zoo Animals & Plants Available at: http://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/reindeer. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Stephen Sharnoff & Sylvia Sharnoff. Lichens and Wildlife. Lichens of North America Information Available at: http://www.lichen.com/animals.html. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Amos Chapple & Wojtek Grojec. Chernobyl’s Reindeer. (2016). Available at: http://www.rferl.org/fullinfographics/infographics/chernobyls-reindeer/27575578.html. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- ITIS Standard Report Page: Trebouxia. Integrated Taxonomic Information System (2014). Available at: https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=5653#null/. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Cladonia rangiferina. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?Table=Mycobank&Rec=207295&Fields=All. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Cladonia arbuscula. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?Table=Mycobank&Rec=208192&Fields=All. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Cladonia mitis. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?Table=Mycobank&Rec=195485&Fields=All. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Cladonia stellaris. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?Table=Mycobank&Rec=186693&Fields=All. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Cladonia stygia. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?Table=Mycobank&Rec=193041&Fields=All. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- Cladina subtenuis. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/BioloMICS.aspx?Table=Mycobank&Rec=310178&Fields=All. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

- ITIS Standard Report Page: Rangifer tarandus. Integrated Taxonomic Information System Available at: https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=180701#null/. (Accessed: 23rd December 2016)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

1 Response

[…] Reindeer Lichen, commonly called Reindeer Moss Canaan Mt 9/2/19 https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/171-reindeer-lichen/ […]