#163: Valley Fever, Coccidioidomycosis

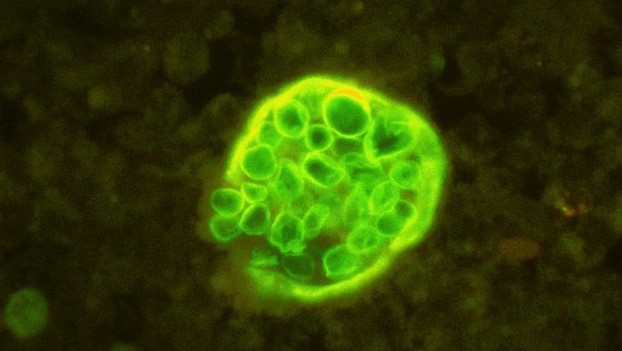

Fluorescent stain of a Coccidioides sp. infective spherule releasing endospores. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

Coccidioidomycosis, otherwise known as “Valley fever,” is the most virulent human fungal pathogen. The disease is caused by the fungi Coccidioides immitis and C. posadasii, which normally live in arid soils. When they are disturbed by wind, construction, or human activity, spores from these fungi can become airborne and end up in peoples’ lungs. There, the spores germinate and can cause infection. Most of the time, the infection is mild and does not need to be treated. Occasionally, however, this progresses to more severe forms that sometimes require lifelong treatment. As with other human fungal diseases, Valley fever is more likely to cause severe disease in people with weakened immune systems.i

Pathogen Biology

Valley fever is caused by the fungi C. immitis and C. posadasii, which are virtually indistinguishable from one another. There are enough differences in their DNA for them to be considered separate species, but neither morphological features nor differences in symptomology are distinctive enough to separate the two species.ii

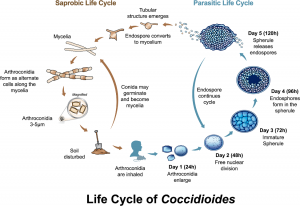

Both Coccidioides species share a common life cycle. Like the other true human pathogenic fungi, these two are dimorphic: they have a hyphal phase for growth in the environment and a yeast phase for growth inside a host.iii

By Lewis ERG, et al. [CC BY 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

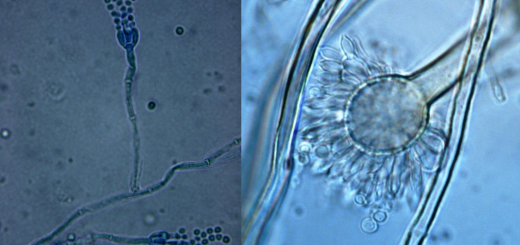

The yeast phase of the Coccidioides life cycle is characterized by the formation of individual, rounded cells. This phase is triggered when an arthroconidium lands in an animal’s lung. Arthroconidia are very small and can reach some of the tiniest spaces in the lungs. When this happens, the spores discard their protective cell wall and swell 4 to 20 times their size to become yeast-like cells called “spherules.” Each spherule has a thick double wall and contains multiple nuclei. After growing for two or three days, the spherule divides its contents into hundreds to thousands of spores called “endospores.” Once division is complete, the spherule ruptures and releases the endospores. Each endospore germinates to form a spherule, thus propagating the infection.vii

Distribution

Arthroconidia (dark blue) developing in Coccidioides sp. hyphae. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

The range of Valley fever is limited by the distribution of the causal agents. C. immitis is found in the San Joaquin Valley of central Californiaviii (a longer name for coccidioidomycosis is “San Joaquin Valley fever,” so the “Valley” in the name “Valley fever” refers to that area of Californiaix). C. posadasii has a larger range. It grows in arid to semi-arid areas of the American Southwest (including parts of Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah), parts of Central America (including areas in northern Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua), and some areas of South America (including places in Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Venezuela). The pathogens do not occur outside the Western Hemisphere. Knowing where the infection was acquired is the easiest way to differentiate between the two species, since the morphology and symptoms are the same in both species.x Recently, the fungus has also been found in some south-central areas of Washington State.xi

Within its native range, the distribution of C. immitis or C. posadasii is highly variable. Places that test positive for the organisms one year may test negative the next. Researchers do not know why this happens. Weather is the most important factor affecting the range of Coccidioides species, but that alone cannot account for the patchy distribution of the organisms. Unfortunately, rising temperatures related to global climate change are likely to increase the native range of both species, putting more people at risk of infection.xii

Occasionally, Valley fever can spread outside its native range thanks to sandstorms and human activity. Sandstorms are dangerous because they pick up the fungal spores and distribute them across a wide area. Sometimes, this can cause infection outside of endemic areas. The spores can also be carried out of their native range in dust clinging to clothing, boots, or even cars.xiii

Because the disease is limited to certain regions, it is not seen as a threat by people outside of endemic areas. Unfortunately, this means that politicians and corporations are not willing to spend money on Valley fever research.xiv

Risk Factors

How likely someone is to contract Valley fever depends upon how common the pathogen is in their area. In 2011, the reported incidence of disease was 42.6 infections per 100,000 people in U.S. states where the disease occurs naturally.xv The actual number of infections in the U.S. per year is likely around 150,000, since most infections are mild and testing for coccidioidomycosis is infrequent.xvi Data from skin tests (which return positive if a patient’s immune system has fought off the disease before) suggest that over 80% of people who have lived in endemic areas for more than five years have had the disease.xvii

The number of cases can also fluctuate from year to year, a result of variations in weather, human migration, and reporting practices. For example, the highest incidence in recent years occurred during 2011, when 22,641 cases were recorded. In 2014, however, there were only 8,232 reported cases.xviii

Between the years of 1998 and 2011, there was a ten times increase in the number of Valley fever cases per year. The cause of this is unclear, but may be related to the growth of cities and suburbs in endemic areas. As a result of these growing populations, more people are exposed to Coccidioides spores.xix

Although anyone who lives in or visits Valley fever endemic areas can contract the disease, activities and occupations that disturb dusty soil increase one’s chances of getting sick. It only takes one spore to cause disease, but inhaling a greater number of spores increases the likelihood that at least one will germinate to become infectious.xx Certain jobs put people at an increased risk for disease by exposing them to a greater number of spores. These include: construction, farming, archaeology, and certain jobs in the oil industry. People studying coccidioidomycosis in a laboratory setting have a particularly high risk for infection because the spores produced by fungi are easily swept up into air currents and lab accidents can expose people to a high number of spores all at once (C. immitis and C. posadasii are classified as Bio Safety Level 3 organisms).xxi Other events that generate dust, such as hot and dry weather, also result in an increase in the number of infections.xxii

As with other fungal infections, people with weakened immune systems are more susceptible to the disease. Consequently, Valley fever is a particular concern for people taking immunosuppressant drugs and those living with HIV/AIDS. Pregnant women and people who have diabetes are also more likely to develop a more severe infection.xxiii Additionally, people of African or Filipino descent are more susceptible to the pathogen (and to a lesser extent, so too are Asians, Hispanics, and Native Americans).xxiv Adults over the age of 60 are more likely to be diagnosed with the disease than other age groups.xxv Other animals can also get Valley fever and dogs are particularly at risk.xxvi

Fortunately, most people who have had Valley fever once will never get it again. Some patients will have a relapse, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describe this event as “very rare.”xxvii Because patients cannot get the disease a second time, migration has a high impact on the number of cases. If more unexposed people move to or find temporary work in endemic regions, then rates of infection will increase. For example, an increase in military personnel stationed in the San Joaquin Valley during World War II caused a noticeable rise in the number of cases.xxviii This can also be a problem for people from other areas of California who are sent to prison in the San Juaquin Valley.xxix

Under normal conditions, coccidioidomycosis cannot be transmitted from person to person. As of 2002, there were only five known cases of person to person transmission, and all involved unusual circumstances. The most likely of these to happen again are the three cases where Valley fever was transmitted to premature babies.xxx Other possible methods of person to person transmission include receiving an organ transplant infected with a Coccidioides species and inhaling spores from an infected wound.xxxi

Symptoms

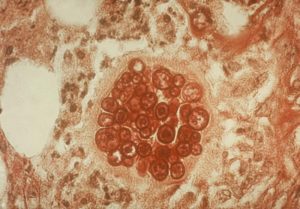

Coccidioides sp. spherule with developing endospores infecting tissue. Public domain image By UNK (http://phil.cdc.gov/phil/), via Wikimedia Commons.

Valley fever generally comes in three forms: acute, chronic, and disseminated. In the acute form, infection usually occurs in the lungs and the immune system causes minor inflammation in order to access and fight the fungus.xxxii Most people get the acute form, where the body is able to clear the disease in a manner of weeks or months. Within this group, there are many people who are asymptomatic and never know they had the disease. People who do get symptoms normally experience: fatigue, cough, fever, shortness of breath, headache, sweating at night, aching muscles and joints, and sometimes a rash on the legs or upper body.xxxiii This rash is the result of an allergic reaction to the fungus and is known as “desert bumps.”xxxiv Symptoms usually appear within 1-3 weeks after infection.xxxv

In the chronic form of coccidioidomycosis, the initial immune response is insufficient to clear the fungi. As a result, the immune system increases inflammation, recruits more immune cells to the area, and attempts to wall off the foreign organisms.xxxvi This type of infection is still limited to the lungs, so symptoms are primarily respiratory-related. Only about 5-10% of patients develop chronic infections.xxxvii

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis is the most severe form of the disease. In this form, the fungus escapes from the lungs and gets into the lymphatic system and blood stream. From there, the spherules can access and invade tissue in any part of the body.xxxviii This can lead to a diverse range of symptoms, depending upon which organs are infected and impaired. Lesions in the skin are a common symptom of disseminated coccidioidomycosis.xxxix Disseminated coccidioidomycosis also frequently affects the joints, soft tissues, and central nervous system, often causing meningitis. This severe form of the disease progresses quickly and can be fatal, especially when meningitis is involved.xl Only about 1% of infections will result in disseminated coccidioidomycosis.xli

Treatment

Proper treatment of Valley fever relies on accurate diagnosis. This is often hampered by the fact that doctors outside endemic regions are unfamiliar with the disease. Consequently, people who acquired the infection while traveling or through an uncommon mechanism are less likely to receive a proper diagnosis and treatment.xlii

Coccidioidomycosis can be diagnosed through a combination of blood tests, x-rays, and sampling. Blood tests are available to detect antibodies against Coccidioides in people with healthy immune systems. Chest x-rays are performed to look for lesions, growths, or other abnormalities specific to Valley fever. Since these do not necessarily mean a Coccidioides species is causing infection, samples of infected tissues or fluids from infection sites can be taken. To identify the infectious agent, these samples are either examined under the microscope or cultured in a lab.xliii

Various antifungal drugs are used to treat Valley fever. The first drug of choice is fluconazole, particularly for mild to moderate infections. Another azole may be used, depending on a particular patient’s situation. These other drugs include: itraconazole (which is used almost as often as fluconazole), voriconazole, and posaconazole. Fluconazole is also used in cases where coccidioidomycosis leads to meningitis. The most serious cases are treated with amphotericin B. In mild cases, treatment usually lasts three to six months. Patients with severe cases need to be treated for much longer periods of time. For some, the infection clears up after a number of years. Unfortunately, those with the most aggressive form of the disease may need lifelong treatment.xliv

Taxonomy

Coccidioides belongs to the phylum Ascomycota, which includes most yeasts and lichens as well as large mushrooms like morels. Interestingly, most (if not all) of the true human pathogenic fungi also belong to the order Onygenales, although they do come from a variety of different lineages within that group.xlv

The genus name Coccidioides means “like Coccidia.” The mycologist who originally named the genus apparently thought the spherule stage of these organisms looked like the protozoan parasite Coccidia, which infects chickens. The specific epithet immitis means “not mild,” while posadasii refers to the researcher who originally described the disease, Alehandro Posadas.xlvi [Side note: the first known patient with coccidioidomycosis was Domingo Ezcurra. His head is preserved in a jar at the University of Buenos Aires’s School of Medicine. Tom Volk’s page has a photo of this.]xlvii

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Phylum | Ascomycota |

| Subphylum | Pezizomycotina |

| Class | Eurotiomycetes |

| Subclass | Eurotiomycetidae |

| Order | Onygenales |

| Family | Onygenaceae |

| Genus | Coccidioides |

| Species | C. immitis G.W. Stilesxlviii |

| C. posadasii M.C. Fisher, G.L. Koenig, T.J. White & J.W. Taylorxlix |

See Further:

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/215978-overview#showall

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/01/20/death-dust

http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/jan2002.html

http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/index.html

https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/infections/fungal-infections/coccidioidomycosis

Citations

[i] Thomas J. Volk, “Coccidioides Immitis, Cause of Coccidioidomycosis, Aka Valley Fever, San Joaquin Valley Fever, Desert Bumps, Desert Rheumatism or Posadas’ Disease, California Disease, Bioterrorism, Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for January 2002,” Tom Volk’s Fungi, January 2002, http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/jan2002.html.

[ii] Duane R Hospenthal et al., “Coccidioidomycosis,” Medscape, October 7, 2016, http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/215978-overview.

[iii] Thomas J. Volk, “Coccidioides Immitis, Cause of Coccidioidomycosis, Aka Valley Fever, San Joaquin Valley Fever, Desert Bumps, Desert Rheumatism or Posadas’ Disease, California Disease, Bioterrorism, Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for January 2002,.”

[iv] Duane R Hospenthal et al., “Coccidioidomycosis.”

[v] Thomas J. Volk, “Coccidioides Immitis, Cause of Coccidioidomycosis, Aka Valley Fever, San Joaquin Valley Fever, Desert Bumps, Desert Rheumatism or Posadas’ Disease, California Disease, Bioterrorism, Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for January 2002,.”

[vi] Duane R Hospenthal et al., “Coccidioidomycosis.”

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Thomas J. Volk, “Coccidioides Immitis, Cause of Coccidioidomycosis, Aka Valley Fever, San Joaquin Valley Fever, Desert Bumps, Desert Rheumatism or Posadas’ Disease, California Disease, Bioterrorism, Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for January 2002,.”

[x] Duane R Hospenthal et al., “Coccidioidomycosis.”

[xi] “Definition of Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis),” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 5, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/definition.html.

[xii] Dana Goodyear, “Death Dust,” The New Yorker, January 20, 2014, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/01/20/death-dust.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] “Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis) Statistics,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 5, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/statistics.html.

[xvi] Duane R Hospenthal et al., “Coccidioidomycosis”; “Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis) Statistics.”

[xvii] Duane R Hospenthal et al., “Coccidioidomycosis.”

[xviii] “Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis) Statistics.”

[xix] Dana Goodyear, “Death Dust.”

[xx] Duane R Hospenthal et al., “Coccidioidomycosis.”

[xxi] Ibid.; Dana Goodyear, “Death Dust.”

[xxii] “Sources of Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis),” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, April 4, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/causes.html.

[xxiii] “Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis) Risk & Prevention,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 2, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/risk-prevention.html.

[xxiv] John N. Galgiani et al., “Coccidioidomycosis,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 41, no. 9 (November 1, 2005): 1217–23, doi:10.1086/496991.

[xxv] “Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis) Statistics.”

[xxvi] “Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis) Risk & Prevention.”

[xxvii] Ibid.

[xxviii] Dana Goodyear, “Death Dust”; Duane R Hospenthal et al., “Coccidioidomycosis.”

[xxix] Dana Goodyear, “Death Dust.”

[xxx] Thomas J. Volk, “Coccidioides Immitis, Cause of Coccidioidomycosis, Aka Valley Fever, San Joaquin Valley Fever, Desert Bumps, Desert Rheumatism or Posadas’ Disease, California Disease, Bioterrorism, Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for January 2002,.”

[xxxi] “Sources of Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis).”

[xxxii] Duane R Hospenthal et al., “Coccidioidomycosis.”

[xxxiii] “Symptoms of Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis),” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 2, 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/symptoms.html.

[xxxiv] Thomas J. Volk, “Coccidioides Immitis, Cause of Coccidioidomycosis, Aka Valley Fever, San Joaquin Valley Fever, Desert Bumps, Desert Rheumatism or Posadas’ Disease, California Disease, Bioterrorism, Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for January 2002,.”

[xxxv] Sanjay G. Revankar and Jack D. Sobel, “Coccidioidomycosis,” Merck Manuals Consumer Version, accessed October 21, 2016, https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/infections/fungal-infections/coccidioidomycosis.

[xxxvi] Duane R Hospenthal et al., “Coccidioidomycosis.”

[xxxvii] “Symptoms of Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis).”

[xxxviii] Duane R Hospenthal et al., “Coccidioidomycosis.”

[xxxix] Thomas J. Volk, “Coccidioides Immitis, Cause of Coccidioidomycosis, Aka Valley Fever, San Joaquin Valley Fever, Desert Bumps, Desert Rheumatism or Posadas’ Disease, California Disease, Bioterrorism, Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for January 2002,.”

[xl] Duane R Hospenthal et al., “Coccidioidomycosis.”

[xli] “Symptoms of Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis).”

[xlii] Dana Goodyear, “Death Dust.”

[xliii] Sanjay G. Revankar and Jack D. Sobel, “Coccidioidomycosis.”

[xliv] Ibid.

[xlv] Thomas J. Volk, “Coccidioides Immitis, Cause of Coccidioidomycosis, Aka Valley Fever, San Joaquin Valley Fever, Desert Bumps, Desert Rheumatism or Posadas’ Disease, California Disease, Bioterrorism, Tom Volk’s Fungus of the Month for January 2002,.”

[xlvi] Ibid.

[xlvii] Ibid.; Dana Goodyear, “Death Dust.”

[xlviii] “Index Fungorum – Names Record 416228,” Index Fungorum, accessed October 21, 2016, http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/NamesRecord.asp?RecordID=416228.

[xlix] “Index Fungorum – Names Record 484628,” Index Fungorum, accessed October 21, 2016, http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/NamesRecord.asp?RecordID=484628.

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)