#116: Scorias spongiosa

This bizarre fungus forms a fuzzy mat of tan to black tissue on the branches, trunks, and ground underneath American Beech trees. Scorias spongiosa belongs to a group of fungi called “sooty molds.” Sooty molds digest the honeydew (essentially sugar-rich aphid poop) dropped by aphids in the process of feeding on plants. There are many kinds of sooty molds and if you’ve ever had an aphid (or other insect) infestation on trees in your garden, they you’ve probably seen sooty molds. Normally, sooty molds form a thin, black film on leaves and branches under places where the aphids are feeding. spongiosa differs from normal sooty molds because it forms films that can be as thick as a football!

S. spongiosa can be found only on and underneath American Beech (Fagus grandifolia) trees infested with the Beech Blight Aphid (a.k.a. Beech Woolly Aphid, Grylloprociphilus imbricator). Because the fungus relies entirely upon the aphids for food, we need to discuss the American Beech and the Beech Blight Aphid so we can more fully understand the fungus’s life cycle.

Unfortunately, trees are not my strong suit, so American Beech will not receive much attention in this post. American Beech trees are common trees in Eastern North American forests. Their native range extends from Louisiana up to Michigan and across to the Atlantic Coast. The Beech Blight Aphid and its associated fungus can be found all across this range. This tree is the only member of its genus found in North America, so it can easily be identified by its exceptionally smooth bark (beech = smooth as a *beach*). Because its bark is so smooth, beech trees often have names, initials, and other graffiti carved into them. Beeches are slow-growing, deciduous trees that reach heights of 24m (80ft) or more. For more information on the American Beech, see the Forest Service brochure linked below.*

Beech Blight Aphids are common pests of American Beech trees. In April, a female Beech Blight Aphid (at this point known as a “fundatrix”) emerges from her egg, finds a good spot on her beech tree to feed, and begins producing thousands of parthenogenic (cloned) offspring. These young aphids do not travel very far, so they end up forming large colonies that can be over 1.5m (5ft) across. Each aphid is light blue in color, produces waxy threads from its abdomen, and lacks wings. Aphids from the second female generation produced in that year (known as “sexuparae”) do grow wings and come out sometime between June and November. When disturbed, the aphids stick their abdomens high into the air and wave them around. Thanks to this rather unusual defense tactic, the aphids are sometimes called “Boogie-Woogie Aphids.” Colonies of Beech Blight Aphids often make the infected branches look like they are covered in snow or cotton. Most colonies do not appear until late August or early September, though a few scattered colonies may appear in early summer. The colonies generally persist until late October or perhaps the end of November.

Beech Blight Aphids produce much more honeydew than most other aphids. Because the aphids form colonies, this honeydew is concentrated in the area just below the colony. Most aphids do not form colonies, so their honeydew is spread all around the infected plant, rather than just in certain spots. As a result, S. spongiosa is able to grow large masses while most sooty molds can form only thin films.

S. spongiosa can be found wherever honeydew from the aphid colonies falls. Windblown spores from the fungus land on the honeydew and begin growing and decomposing the sugars. At first, the fungal growth is inconspicuous and it may be easier to look for the aphid colonies in order to find the fungus. This quickly changes as more honeydew accumulates on the branches, leaves, and ground below the aphid colony.

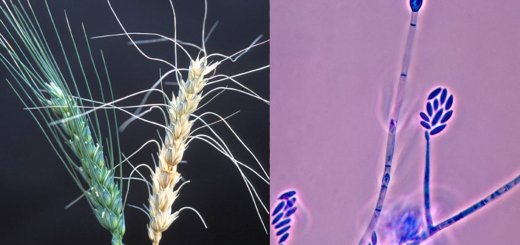

The initial fungal growth is thin, yellowish to light tan, and fuzzy. The fuzziness comes from hyphae sticking out to find new places to grow and from spore-producing structures called “pycnidia.” Pycnidia are flask-shaped structures that produce asexual spores. The spores are released into liquid droplets that form at the top of each pycnidium.

As the fungus grows in size, it starts to look like a sponge or a clump of dried moss and acquires a texture that is firmly gelatinous to spongy. Thanks to the generous amount of honeydew produced by Beech Blight Aphid colonies, masses of S. spongiosa regularly grow to 15cm (6in) in diameter, although masses on tree trunks can get much larger.

At this point, older parts of the fungus start to turn black, produce sexual spores, and develop an airy, sponge-like texture. These spores are produced in different flask-shaped structures called “pseudothecia,” which are formed within the black fungal tissue. By late fall, all the fungal tissue will have turned black and become thick and crusty. These structures are fairly resilient and can last well into winter.

Neither the fungus nor the aphids significantly impact the health of their host tree. Although Beech Blight Aphids cause local damage, the overall health of the tree is usually unaffected. S. spongiosa does not feed on plant tissues, so it causes very little harm to the tree. It may coat leaves on lower branches, which can reduce the tree’s ability to photosynthesize. This effect is negligible for a full-grown tree, but can kill seedlings growing below the infested tree. If the same tree is infested year after year, the area around the beech may become devoid of seedlings, thus impairing forest regeneration in that area. One positive impact of the fungus is that leaves coated with S. spongiosa are more efficient at absorbing air pollution. Of course, one of the most significant impacts of the fungus and aphids is as a nuisance to gardeners. If you don’t like the black fungus coating your plants underneath a beech tree, you have to treat the aphids on the tree. Without a supply of honeydew, the fungus can easily be removed. There are a number of products available to treat aphid infestations. Visit your local gardening center for advice on removing the aphids.

See Further:

http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/sep2007.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4081282/

http://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/scorias_spongiosa

* http://www.na.fs.fed.us/pubs/silvics_manual/volume_2/fagus/grandifolia.htm

![#049: Coffee Rust [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-medium-empty.png)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

1 Response

[…] group you might have heard of are Apple Scab Disease (Venturia inequalis) and Scorias spongiosa (FFF#116). The distinguishing characteristic of Dothideomycetes is that their asci have two layers and are […]