#081: Phellinus robiniae, the Cracked Cap Polypore

Phellinus robiniae, the Cracked Cap Polypore, gets its common name from its deeply furrowed cap. The easiest way to identify P. robiniae is by identifying the tree it grows on. The mushroom appears almost exclusively on locust trees.

Phellinus robiniae, commonly known as the “Cracked Cap Polypore,” is a woody bracket fungus that is most easily identified by its habitat. This fungus grows almost exclusively on locust trees. In fact, the fungus is such a common pathogen of locusts that nearly every Black Locust tree has at least one P. robiniae mushroom on it. The mushroom is also distinguished by its furrowed cap – which gives the fungus its common name – and its dull brown pore surface.1–3

Description

Phellinus robiniae is just one of many woody brown polypores that can be found growing on living or recently deceased trees. It usually appears on the side of a tree and grows out and down in semicircular layers from its point of attachment.1–3

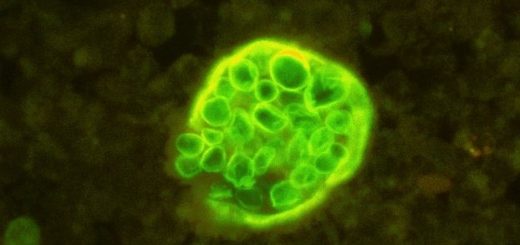

The Cracked Cap Polypore has a smooth brown pore surface that seems to shimmer when you look at it from different angles.

As its common name suggests, one of the defining features of the Cracked Cap Polypore is its pileus, which becomes deeply cracked in age. When young, this polypore’s cap is light brown and may be velvety. The mushroom is perennial, so a new pore surface is added to the bottom of the mushroom every year. From above, the new growth appears along the edges of the cap as a light brown, possibly velvety ring. The older layers at the center of the cap stop growing and become dark brown or black and develop deep cracks with age. At first the mushroom forms a flattish bracket, but this becomes more conical to hoof-shaped as further layers are added to the bottom. The Cracked Cap Polypore can get fairly big; large specimens grow up to 40cm in diameter and 20cm thick.1–3

From below, the mushroom appears fairly uniform. The brown pore surface is composed of tiny pores (7-8 per millimeter), so it looks completely smooth from a distance. Despite their small size, you can tell the pores are there because the surface seems to shimmer when you tilt it back and forth. The pore surface attaches to the tree at a roughly 90° angle and tends to curve down at the edges in older specimens. Most other polypores are lower around the center and higher around the edges – opposite of what P. robiniae does. P. robiniae has a brown spore print, so you’ll often find a brown smudge running down the tree below the mushroom.1–3

P. robiniae produces brown spores that often leave streaks underneath the mushroom. The mushrooms can get fairly large, as demonstrated in this picture.

Ecology

The Cracked Cap Polypore is a parasitic and saprobic species that infects living and dead wood of Robinia trees. P. robiniae selectively degrades the lignin in trees, causing a white rot. Infected trees are usually either Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) or New Mexican Locust (Robinia neomexicana).1,3 Infection by P. robiniae is so pervasive among Black Locust trees that nearly every tree-sized Black Locust you find has at least one Cracked Cap Polypore mushroom on it. The success of P. robiniae is aided by the Locust Borer beetle, Megcallene robiniae, which tunnels into the wood of locust trees and creates openings for the fungus to attack.4 P. robiniae occasionally appears on other trees including: acacias, chestnuts, walnuts, mesquites, and oaks (although very similar species also occur on those trees, making identification much more difficult).1,3 The Cracked Cap Polypore grows wherever its host trees are present, which today includes most of North America and some parts of Europe and Asia.1,4

Locust Trees

Often, the Cracked Cap Polypore grows too high on the tree for you to examine it closely. In these situations, the ability to identify tree species can be an invaluable tool. If you ever find a brown woody polypore on a locust tree, you can bet it’s the Cracked Cap Polypore. So how do you identify a locust tree? Depending on the time of year, there are four things you can examine: leaves, flowers, seeds, and bark.

Locust tree leaves are pinnately compound; leaflets branch off of a central stalk. Photo by Brosen [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC BY 2.5], from Wikimedia Commons.

In the spring, locusts produce clusters of white flowers that hang down from their branches. Photo by Archenzo [CC BY-SA 3.0] via Wikimedia.

If you have found this tree in late winter when none of the preceding characteristics are available, you can still look at the bark. Identifying trees based on bark is very difficult, but locust bark is fairly distinctive. The bark is light gray and deeply furrowed in Black Locust but only shallowly furrowed in New Mexican locust. There are a number of trees with furrowed bark, so if you are unsure of what locust bark looks like, then look for the distinctive thorns on the smaller branches.4–6

Locust trees produce seed pods (they are in the bean family, after all) that dry out and slowly drop their seeds. Photo by Bogdan [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

One of your best bets for finding fully-grown locust trees is in gardens. Because of their widespread use in gardens, Black Locusts (originally from the Appalachians and Ozarks) have become naturalized in much of the United States and parts of Europe and Asia.4 This is good news for the Cracked Cap Polypore, which has traveled around the world with its host tree.8 The New Mexico Locust prefers mountainous regions in the American Southwest, so geographical range helps distinguish between these two very similar trees.5,7

Similar Species

“Brownish woody polypore on a tree” describes numerous species of polypores. Ganoderma applanatum (FFF#070) is the most similar mushroom discussed on Fungus Fact Friday. Others that spring to mind are Phellinus everhartii (which is very similar but grows on oaks), Fomes fomentarius (FFF#189) and Fomitopsis pinicola. The Cracked Cap Polypore’s dull brown pore surface and growth on Black Locust trees are the two features that best distinguish it from similar polypores.

Black Locust bark has deep criscrossing furrows. You can also check for the presence of the Cracked Cap Polypore, which is usually somewhere on the tree!

Edibility and Uses

As far as I know, this mushroom isn’t used for anything. It is inedible due to its woody texture and it does not have any medicinal benefits. However, lots of people seem to think it is medicinal, probably because of how similar it is to certain medicinal polypores. I once met a woman who swore that the same mushroom grows in Korea and that the Koreans use it medicinally. After a brief search through Wikipedia, I think she may have been thinking of Phellinus linteus, which is considered medicinal. That mushroom is very similar but has a slightly more rounded shape and grows on mulberry trees. 9 This is an example of how region-specific mushroom knowledge is. Because there are so many species of very similar mushrooms, it is dangerous to compare mushrooms across continents; mushrooms you think you know could be different species with different levels of toxicity (this is what makes Amanita phalloides so dangerous in North America, see FFF#051). Fortunately for North American foragers, P. robiniae and its lookalikes are nonpoisonous.

When collecting mushrooms for eating or medicinal uses, you should also consider the mushroom’s local environment. Black Locust trees often grow next to roadways, so you often find P. robiniae in polluted environments. Any mushrooms growing near roads been exposed to high levels of car exhaust and other roadway pollutants. To make matters worse, P. robiniae is perennial, so the mushrooms have soaked up those chemicals for multiple years. Cracked Cap Polypores growing under these conditions are probably slightly toxic, especially if you consume them over a long period of time.

To summarize, the Cracked Cap Polypore is harmless but useless in ideal conditions but can be poisonous in contaminated environments.

Taxonomy

P. robiniae belongs to the order Hymenocheatales. The core polypores belong to the order Polyporales, so the Cracked Cap Polypore is not related to most other polypores.10 There is some debate over the proper genus for the Cracked Cap Polypore. Mycologists currently place it in Phellinus, but some research suggests it should belong to Fulvifomes.1 As with most mushroom names, don’t be surprised if it changes in the near future. Fulvifomes belongs to the same order and family as Phellinus, so the mushroom’s taxonomic relationships wouldn’t change very much with its new genus.11

Phellinus means “corky” and robiniae means “on Robinia,” so Phellinus robiniae is an apt name for this species.2

| Common Name | Cracked Cap Polypore | Black Locust

New Mexican Locust |

| Kingdom | Fungi | Plantae |

| Subkingdom | – | Viridiplantae |

| Infrakingdom | – | Streptophyta |

| Superdivision (Superphylum) | – | Embryophyta |

| Division (Phylum) | Basidiomycota | Tracheophyta |

| Subdivision (Subphylum) | Agaricomycotina | Spermatophytina |

| Class | Agaricomycetes | Magnoliopsida |

| Superorder | – | Rosanae |

| Order | Hymenochaetales | Fabales |

| Family | Hymenochaetaceae | Fabaceae |

| Genus | Phellinus | Robinia |

| Species | Phellinus robiniae (Murrill) A. Ames10 | Robinia pseudoacacia L.12

Robinia neomexicana A. Gray13 |

This post does not contain enough information to positively identify any mushroom. When collecting for the table, always use a local field guide to identify your mushrooms down to species. If you need a quality, free field guide to North American mushrooms, I recommend Michael Kuo’s MushroomExpert.com. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out!

See Further:

http://www.mushroomexpert.com/phellinus_robiniae.html

http://www.messiah.edu/oakes/fungi_on_wood/poroid%20fungi/species%20pages/Phellinus%20robiniae.htm

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_2/robinia/pseudoacacia.htm

http://dendro.cnre.vt.edu/dendrology/syllabus/factsheet.cfm?ID=317

https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/Robinia-pseudoacacia.shtml

http://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/robinia_neomexicana.shtml

Citations

- Kuo, M. Phellinus robiniae. MushroomExpert.Com (2010). Available at: http://www.mushroomexpert.com/phellinus_robiniae.html. (Accessed: 13th April 2018)

- Emberger, G. Phellinus robiniae. Fungi Growing on Wood (2008). Available at: http://www.messiah.edu/Oakes/fungi_on_wood/poroid%20fungi/species%20pages/Phellinus%20robiniae.htm. (Accessed: 13th April 2018)

- Labbé, R. Fulvifomes robiniae / Polypore du robinier. Les champignons du Québec (2014). Available at: https://www.mycoquebec.org. (Accessed: 13th April 2018)

- Huntley, J. C. Black Locust. Southern Research Station (1990). Available at: https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_2/robinia/pseudoacacia.htm. (Accessed: 13th April 2018)

- Taylor, D. Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia). U.S. Forest Service Available at: https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/Robinia-pseudoacacia.shtml. (Accessed: 13th April 2018)

- Seiler, J., Jensen, E., Niemiera, A. & Peterson, J. Robinia pseudoacacia Fact Sheet. Virginia Tech Dendrology Available at: http://dendro.cnre.vt.edu/dendrology/syllabus/factsheet.cfm?ID=40. (Accessed: 13th April 2018)

- McDonald, C. New Mexico locust (Robinia neomexicana). U.S. Forest Service Available at: https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/robinia_neomexicana.shtml. (Accessed: 13th April 2018)

- Sheppard, A. W., Shaw, R. H. & Sforza, R. Top 20 environmental weeds for classical biological control in Europe: a review of opportunities, regulations and other barriers to adoption. Weed Research 46, 93–117 (2006).

- Phellinus linteus. Wikipedia (2018).

- Phellinus robiniae. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/Biolomics.aspx?Table=Mycobank&Rec=20496&Fields=All. (Accessed: 13th April 2018)

- Fulvifomes robiniae. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/Biolomics.aspx?Table=Mycobank&Rec=71334&Fields=All. (Accessed: 13th April 2018)

- Robinia pseudoacacia L. Integrated Taxonomic Information System Available at: https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=504804#null. (Accessed: 13th April 2018)

- Robinia neomexicana A. Gray. Integrated Taxonomic Information System Available at: https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=26196#null. (Accessed: 13th April 2018)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

There are papers suggesting benefits for diabetics.

Used as a coal extender in the tinder bundle for friction fire.