#049: Coffee Rust

Coffee Rust, caused by the pathogenic fungus Hemileia vastatrix, has severely impacted coffee growers in Central America in recent years. Photo by Smartse [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

History

Coffee Rust was first recorded in 1861 on wild coffee trees in the Lake Victoria region of Africa. Eight years later the disease was identified on the leaves of coffee trees in British-owned Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and the pathogen was described as Hemileia vastatrix. By 1879 it had become too well established in the coffee plantations of Ceylon to eradicate. Eventually coffee was no longer a profitable enterprise on the island and the British planted tea there instead. It is not known how the disease was able to travel across the Indian Ocean, but humans probably played a crucial role. Within a few years the disease had spread to India, Sumatra, and Java.1

The resulting decline in coffee production led to the rise of Central and South America as major coffee growing regions. Strict quarantine protocols kept H. vastatrix from colonizing the Americas until 1970, when it managed to get a foothold in Bahia, Brazil. At that time, almost every coffee tree in the Americas was descended from one rust-susceptible cutting, so the disease spread across the region like wildfire. H. vastatrix managed to escape all the quarantine measures imposed upon it, using the wind to spread long distances. Thankfully, Coffee Rust was unable to spread to trees grown at high altitudes, like most of the arabica trees.1

In 2014, an ongoing outbreak of Coffee Rust in Central America made headlines as it infected 60% to 75% of the region’s coffee trees. In Guatemala alone, this resulted in a 15% drop in coffee output and a corresponding loss of more than 100,000 jobs during the 2012-2014 growing seasons.2 Over the next few years, better weather, resistant trees, and learning to live with the fungus improved coffee production in certain Central American countries. However, production has yet to return to pre-outbreak levels.4–6

Pathogen Biology

To understand what is driving the Central American epidemic of Coffee Rust, you need to know a little about the biology of the organisms involved. H. vastatrix is a rust fungus and as such is an obligate plant pathogen. It can infect only species of Coffea trees, including Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora.1 Both C. arabica and C. canephora are tropical plants native to Africa that are cultivated for their flavorful and caffeinated seeds. C. arabica produces the higher quality arabica beans, is highly susceptible to Coffee Rust, and prefers slightly cooler temperatures than C. canephora (arabica trees are therefore usually grown at higher altitudes). C. canephora produces the lower quality robusta beans that contain more caffeine and is more resistant to disease. About 65% of global coffee production is arabica and the rest is robusta.7,8

Unlike other rust fungi, H. vastatrix has a simple life cycle: infect, produce spores, repeat. A spore lands on the leaf of a host plant and grows hyphae that enter the leaf through a stoma. Inside the leaf, the hyphae extract nutrients from the host cells, which eventually die.1

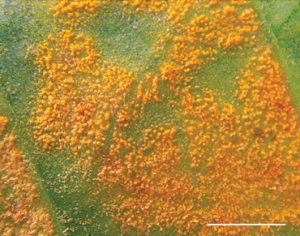

Close-up of a leaf surface covered in spore-producing structures of H. vastatrix. Photo by Carvalho et al. [CC BY 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons

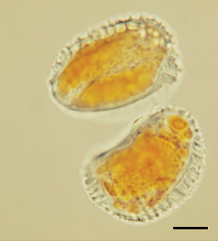

Once the fungus has colonized enough area, it begins producing spores on specialized hyphae that grow out of the leaf’s stomata. The spore masses appear as orange, powdery spots on the undersides of leaves. Although H. vastatrix produces both sexual (teliospores and basidiospores) and asexual (urediniospores) spores, only the asexual spores can infect coffee leaves. Normally, sexual spores produced by rusts infect an alternate host, but no such host has been found for H. vastatrix. The sexual spores Coffee Rust produces may infect an as yet unknown alternate host, but they could also be holdovers from a time in the evolutionary history of H. vastatrix when it did have an alternate host.1

The spores are disseminated by both wind and rain. The effect of rain hitting leaves will propel spores a short distance, while wind can carry the spores long distances. Once the spores land on a new leaf, they need access to liquid water for one to two days in order to successfully germinate. Because of this, they usually germinate during the rainy season. This is advantageous for the fungus because most leaf growth occurs during the rainy season.1

The Recent Central American Outbreak

Global climate change has been proposed as one of the factors been driving the recent epidemic of Coffee Rust in Central America. Because of higher temperatures linked to climate change, the fungus has been able to infect trees at high altitudes that had previously been too cool for H. vastatrix to survive. This allowed the fungus to decimate Central America’s highly susceptible and more valuable arabica trees.2,9

Parts of Central America were also dealing with climate change related drought. Although the fungus struggles to germinate in dry weather, drought can actually make the fungus more virulent. Drought increases stress on the trees, which lowers their natural resistance to infection. This makes Coffee Rust all the more dangerous when rain does arrive.1,10

A recent paper published in the Royal Society journal Philosophical Transactions B suggested that Coffee Rust is not being spurred on by climate change and is instead encouraged by economic factors. This study focused on coffee production in Colombia, which has also experienced outbreaks of Coffee Rust. The authors found many times when the fungus did not spread despite favorable weather. Instead, outbreaks were primarily associated with market downturns, which left farmers unable to properly care for their crops.3 Economics did play a role in the recent outbreak in Central America. Coffee prices have been low for years, leaving farmers without enough money to replace diseased trees.9 The result is more susceptible trees contracting and spreading disease for a longer amount of time.

Disease Management

There are multiple ways to mitigate the effects of H. vastatrix, but so far none has proved successful at eradicating the fungus. The simplest method involves pruning the trees to increase spacing between the leaves. This increases air flow, which allows the leaves to dry quicker and reduces the number of places that water can collect. As a result, spores have access to water for less time, making it less likely that they will germinate. Shade-grown trees appear to be less susceptible thanks to their lower bean yields. A tree that produces fewer beans has more resources available and is therefore healthier in general.1 Fungicides are also effective against Coffee Rust. However, fungicides are too expensive for small farmers, who produce most of the Arabica beans.1,11

Asexual urediniospores of H. vastatrix. These spores are capable of infecting coffee plants. Photo by Carvalho et al. [CC BY 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons

Current Trends

In an attempt to mitigate the epidemic, Guatemala gave out fungicide to small farmers in 2013, but for many it was too little, too late. The Guatemalan government is also providing low-interest loans to coffee farmers to help them weather the epidemic.9 Despite these efforts, Guatemalan coffee production – which rose slightly after 2014 – has been experiencing an annual 3% decline in recent years. This is mainly because large-scale farms closed down in the wake of the rust epidemic.12 Production also remains low in El Salvador and Costa Rica, where since 2014 farmers have continually battled Coffee Rust, drought, and low market prices.4,12

Honduras, Mexico, and Nicaragua, on the other hand, have been successful at recovering from the Coffee Rust outbreak and all three countries are forecast to soon return to pre-outbreak production levels.4 However, Coffee Rust remains a threat to production across the region. In May 2017, the Lempira variety of coffee was found to be susceptible to H. vastatrix infection. Lempira trees were widely planted in Honduras during the 2010’s outbreak because it was resistant to Coffee Rust. Now, that resistance has somehow vanished. Researchers do not know whether one of the H. vastatrix strains already present in Central America (races I and II) has mutated to overcome Lempira’s defenses or whether a new strain to which Lempira is not resistant has arrived in the region.13

Currently, Hawaii is one of the only coffee growing regions that is completely free of Coffee Rust.1 Given the pathogen’s history, it may simply be a matter of time before the disease becomes established in the island chain.

Taxonomy

| Kingdom | Fungi | Plantae |

| Subkingdom | Viridiplantae | |

| Infrakingdom | Streptophyta | |

| Superdivision (Superphylum) | Embryophyta | |

| Division (Phylum) | Basidiomycota | Tracheophyta |

| Subdivision (Subphylum) | Pucciniomycotina | Spermatophytina |

| Class | Pucciniomycetes | Magnoliopsida |

| Superorder | Asteraneae | |

| Order | Pucciniales | Gentianales |

| Family | Rubiaceae | |

| Genus | Hemileia | Coffea |

| Species | Hemileia vastatrix Berk. & Broome14 | Coffea arabica L.15

Coffea canephora Peirre ex A. Froehner16 |

See Further:

http://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/intropp/lessons/fungi/Basidiomycetes/Pages/CoffeeRust.aspx

http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/devastating-coffee-rust-fungus-raises-prices-high-end-blends/

http://gcrmag.com/news/article/leaf-rust-resistant-variety-in-honduras-succumbs-to-pest

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/climate-change-coffee-guatemala_us_589dd223e4b094a129ea4ea2

https://phys.org/news/2016-10-evidence-climate-boosts-coffee-disease.html

Citations

- Arneson, P. A. Coffee rust. The Plant Health Instructor (2000). doi:10.1094/PHI-I-2000-0718-02

- Kahn, C. Rust Devastates Guatemala’s Prime Coffee Crop And Its Farmers. NPR.org (2014). Available at: http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2014/07/28/335293974/rust-devastates-guatemalas-prime-coffee-crop-and-its-farmers. (Accessed: 20th July 2017)

- No evidence climate change boosts coffee plant disease. (2016). Available at: https://phys.org/news/2016-10-evidence-climate-boosts-coffee-disease.html. (Accessed: 20th July 2017)

- Coffee: World Markets and Trade. United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service (2017). Available at: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/coffee.pdf. (Accessed: 20th July 2017)

- Coffee: World Markets and Trade. United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service (2016). Available at: http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/fas/tropprod//2010s/2016/tropprod-12-16-2016.pdf. (Accessed: 20th July 2017)

- Coffee: World Markets and Trade. United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service (2016). Available at: http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/fas/tropprod//2010s/2016/tropprod-06-17-2016.pdf. (Accessed: 20th July 2017)

- Coffee cultivation and species. Paulig Available at: http://www.paulig.com/en/get-inspired-and-learn/everything-about-coffee/coffee-cultivation-and-species. (Accessed: 20th July 2017)

- Coffee. Wikipedia (2017).

- Malkin, E. Fungus Cripples Coffee Production Across Central America. The New York Times (2014).

- Markham, L. Drought And Climate Change Are Forcing Young Guatemalans To Flee To The U.S. Huffington Post (2017).

- Jalonick, M. C. Devastating coffee rust raises prices on high-end blends. PBS NewsHour (2014). Available at: http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/devastating-coffee-rust-fungus-raises-prices-high-end-blends/. (Accessed: 20th July 2017)

- Verdin, M. Central America’s coffee revival hides stark divergence in fortunes. Agrimoney.com (2017). Available at: http://www.agrimoney.com/news/central-americas-coffee-revival-hides-stark-divergence-in-fortunes–10811.html. (Accessed: 20th July 2017)

- Leaf rust resistant variety in Honduras succumbs to pest. Global Coffee Report (2017). Available at: http://gcrmag.com/news/article/leaf-rust-resistant-variety-in-honduras-succumbs-to-pest. (Accessed: 20th July 2017)

- Hemileia vastatrix. Mycobank Available at: http://www.mycobank.org/Biolomics.aspx?Table=Mycobank&Rec=124054&Fields=All. (Accessed: 20th July 2017)

- ITIS Standard Report Page: Coffea arabica. Integrated Taxonomic Information System Available at: https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=35190#null. (Accessed: 21st July 2017)

- ITIS Standard Report Page: Coffea canephora. Integrated Taxonomic Information System Available at: https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=506060#null. (Accessed: 21st July 2017)

![#119: Pisolithus arrhizus, the Dyeball [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-medium-empty.png)

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)