#033: Mushroom Morphology: Morels

It’s finally spring in North America! This has been a very long winter, but now the trees are starting to bloom. To any mushroom enthusiast, this can only mean one thing: it’s the start of morel season!! Keep your eyes peeled for these elusive mushrooms (especially under Tulip Poplars if you’re on the East Coast)! What a morel looks like is a little hard to describe without a picture, so look at the one in the link below. The head of the mushroom is the fertile surface and is defined by an exterior of irregular ridges and pits and a hollow interior. This is often likened to a pinecone, though one with more color and less regularity. The head is held above the ground by a stocky, hollow stipe. The cumulative effect looks somewhat like a pinecone trophy. There are four main species (or perhaps morphological groups) of morels in North America: the Yellow Morels, the Black Morels, the White Morels, and the Half-Free Morels. Yellow Morels (like Morchella esculentoides) are defined by their primarily yellow heads. Black Morels (like Morchella elata) have dark ridges and lighter pits, while White Morels (like Morchella deliciosa) have light ridges and darker pits. In the three morels above, the heads are attached smoothly to the stipe or with a small indentation. The Half-Free Morels (like Morchella semilibera) are distinguished by the small size of the head and by the fact that about half of the head is free from the stipe.

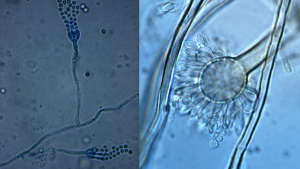

There are a number of morel look-alikes, including verpas (FFF#067) and false morels (FFF#034). Verpas are closely related to morels and look very similar to morels. The distinguishing features of verpas are: a head completely free from the stipe and a stipe with a cottony center. False morels have solid stipes, wrinkles instead of ridges and pits, and heads that are attached to the stipe at the top only. When hunting for morels, make sure you know how to differentiate edible true morels and poisonous false morels. Don’t worry; it’s really not as hard as it sounds. See FFF#034 for more on false morels!

Morels are highly sought after for their taste and texture. However, morels have a complex life cycle and ecology and can only be collected in the wild at certain times. So far, no attempts at commercial production of morels have proven successful. The life cycle of a morel has an extra step that most mushrooms species leave out: the sclerotium. Morels survive the winter by producing large, dense knots of thick-walled mycelium called sclerotia. In the spring, each sclerotium has two options: grow a new mycelium or grow a reproductive mushroom. It is very easy to get sclerotia to grow a mycelium, but they will only grow mushrooms under certain conditions. These conditions have not yet been completely worked out because of the extreme variation in fruiting sites. Morels can be found fruiting in burn sites, under certain healthy trees, under trees that have been dead for a certain length of time, in mulch, or in sites of disturbed ground. East of the Rocky Mountains, morels tend to fruit in early spring (mid-April through early May, or May through June in higher elevations). West of the Rockies, morels seem to enjoy breaking these temporal restrictions. Complicating matters is the morels’ uncertain ecology. Morels can be found fruiting under specific trees, indicating that they are mycorrhizal. However, they also frequently fruit in burn sites and under dead trees (often years after the tree has died), indicating that they are saprobic. It is likely that morels can use both of these strategies at various times.

True morels are all good edible mushrooms, although they should always be cooked before being eaten. Morels dry out very well and can be stored in the dried form for extended periods of time. When you are ready to eat dried morels, they can easily be rehydrated without losing any of their flavor. Verpas are edible for some people but poisonous for others, so use caution when eating these. False morels are often poisonous, so they should be avoided.

Morels are monophyletic, meaning that all the species in this morphological group share a common ancestor. The term “morel” can therefore be used as shorthand for the genus Morchella. Morels and verpas are placed in the Phylum Ascomycota, the Class Pezizomycetes, the Order Pezizales, and the Family Morchellaceae. Recent DNA studies of North American morels have added many new species to the genus Morchella and have removed other putative species. Further DNA studies will probably do the same to the other genera in the Morchellaceae. The family Morchellaceae also contains a genus of cup fungi: Disciotis (see FFF#139 for an example). Mushrooms in the genus Disciotis are cups with a wrinkled to veined spore surface. This genus helps us understand how morels may have evolved into their current morphology. Morels probably started out as cups like Disciotis. Then, they likely evolved a stalk. Next, the cup would have been inverted so that the wrinkles were on the outside. This stage would have looked something like modern verpas. Finally, the head must have re-fused to the stem to create the morel morphology. For a diagram of this theoretical evolutionary path, see Tom Volk’s page on Disciotis venosa*.

This post does not contain enough information to accurately identify any mushroom. Never eat any mushroom without using a field guide to identify it. If you need a free, quality field guide, I recommend Michael Kuo’s MushroomExpert.com.

See Further:

http://www.mushroomexpert.com/morchellaceae.html

http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/morel.html

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

8 Responses

[…] of the cup by a short knob. One of the easiest mushrooms to find this time of year (the start of morel season—get excited!) is Sarcoscypha austriaca. Its bright red colors make it stand out from the […]

[…] Morels, despite their name, are easily distinguished from true morels simply by simply looking at them. If you are new to identifying false morels, there are three […]

[…] Previous story #033: Mushroom Morphology: Morels […]

[…] has a reddish-brown cap that is tightly wrinkled, making it look very similar to true morels (see FFF#033). The easiest way to differentiate Big Red from true morels is to cut it in half; true morels have […]

[…] that family belongs to the order Pezizales, which includes most other cup fungi as well as morels (FFF#033) and their relatives. All these fungi belong to the division Ascomycota (FFF#012), which produce […]

[…] Morchella […]

[…] a handful of species that are encountered occasionally. These mushrooms look a lot like morels (FFF#033), but are attached just at the top of the cap and have a stipe filled with cottony material. The […]

[…] G. brunnea is assumed to be saprobic. However, it does appear in similar habitats to morels (see FFF#033), which can be saprobic or mycorrhizal at different times. This might indicate that G. brunnea can […]