#019: Apiosporina morbosa, Black Knot

And now for something completely different: how to recognize different types of trees from quite a long way away.* Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) is the easiest tree in eastern North America to identify, thanks to the fungus Apiosporina morbosa, commonly known as Black Knot. Most Black Cherry trees are infected with A. morbosa, which causes dark swellings on branches and trunks. Older tree trunks are often marred by large swellings caused by A. morbosa that are up to twice the size of the trunk. These “knots” are easy to spot from a distance (especially in winter), so take advantage of this and amaze your friends by pointing out Black Cherry trees without relying on bark, leaves, or other details! On twigs and smaller branches, Black Knot makes the branches lumpy and thickened in places, looking remarkably like “dried cat poop on a stick” (thank Michael Kuo for that apt analogy).1–3

Description

Black Knot comes in two forms based on its location: on a trunk it grows as a large tumor-like structure while on branches it grows in a cat poop shape.1,2

The tumor-like version appears only on mature tree trunks. It is dark, roughly spherical, and typically wider than the tree trunk. The texture is chunky but still looks a little like normal tree bark (knots are composed of both plant and fungal tissues, so the knots retain some characteristics from the host tree). Lighter-colored wood is usually visible between the chunks. Trunk infections do not seem to cause much harm to mature trees, although other wood decay fungi may enter through the infected area and weaken the trunk.2

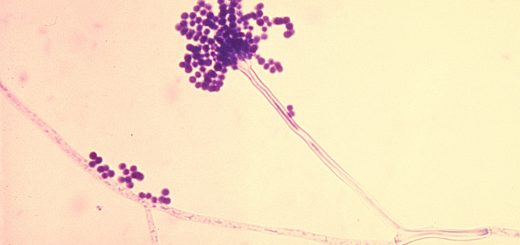

On branches, the fungus takes on its dried-cat-poop-on-a-stick form. These knots are blackish swellings two to three times the width of the branch that taper at both ends. Most branch knots are 3-15 cm long, although older ones can get longer. Branch knots often curve near the center of the knot. The texture is irregularly lobed and furrowed, sometimes breaking apart into separate chunks. If you look closely, you will see that the surface is covered with tiny bumps.1,4–6

Tiny bumps are present on the surfaces of both the tumor-like and cat poop-like versions. These bumps are actually structures called “locules” or “pseudothecia”: flask-shaped structures that contain asci and lack a differentiated outer wall. At the center of each bump there is a tiny hole through which the sexual spores (“ascospores”) are released.4,5,7

Ecology

A. morbosa is a pathogen that attacks cherry and plum trees and occasionally infects peach, date, and many other Prunus trees. In forest settings, you most often find it on Black Cherry. The fungus is widespread and common in North America. Interestingly, historical records indicate the range of A. morbosa was restricted to northeastern North America (it was first described from Massachusetts in 1811) until 1875, when it began appearing in the Midwest.1,4,6,8 In eastern North America, most mature Black Cherry trees have a Black Knot infection on their trunks. Infections of saplings are more variable – I’ve seen some areas where every branch on every sapling has a Black Knot infection and other areas where nearly all saplings are infection-free. The disease does not seem to have much impact on Black Cherry populations.

Life Cycle

The life cycle of A. morbosa begins when an ascospore lands on susceptible host tissue. Ascospores are capable of penetrating the bark on young shoots, so infection typically happens near the tips of branches. The spores can also infect older branches or tree trunks if they land on a wound, possibly caused by a branch falling off or insect damage. The fungus feeds on woody tissue, so A. morbosa cannot infect leaves or fruits. Ascospores are released from about the time buds start opening to about a couple weeks after flowering, so infections typically begin in the spring.4,6

Once infected, the fungus starts growing through the wood and causes the tissue to swell. The fungus grows slowly, so symptoms aren’t noticeable until late summer. At that time, all you can see is a roundish swelling on the twig. This gall is greenish and soft, about the same color and texture as young twig tissue. The surface then takes on a brownish tint as the fungus produces conidia. Conidia can be distributed by rain and wind, but do not appear to be a significant source of new infection.4,6

The fungus remains in the gall over winter and growth resumes the following spring. Over the course of the year, the galls enlarge (which often causes the branch to bend) and become black and bumpy, resulting in the mature “dried cat poop on a stick” shape. The bumps are locules that release ascospores to spread infection to new areas. Depending on the host and climate, the fungus can take up to two years to reach this stage. In subsequent years, the knots continue to elongate and the mycelium can spread inside the plant to produce new knots further down the branch. A. morbosa interferes with the plant’s ability to move resources to and from the branch. Eventually the fungus completely encircles the branch, which stops nutrient transport completely and kills the branch.4,6

As knots age, other fungi and insects (especially boring beetles) begin to invade the knots. The most common fungus to attack A. morbosa is Trichothecium roseum, which causes the locules to turn white or pinkish and prevents spore formation.4,6 Insect and fungal attack help to weaken the knot, so branches often break in the middle of a knot.

A. morbosa primarily kills branches near the tips, so it does not kill its host tree. However, as the infection spreads and to more branches, the tree becomes increasingly stressed.6 This limits the tree’s ability to produce new leaves and makes the tree more susceptible to attack by other fungi and insects. With the help of environmental factors such as wind and drought, these infections can lead to the death of a tree.

Economic Impact and Management

Black Knot is an important disease for North American cherry and plum orchards. Typically, the fungus can reduce yields in plum orchards by about 10% and in cherry orchards by about 1%. However, the disease can be more severe, enough to eliminate entire orchards. In addition to decreasing fruit yields, the fungus also makes lumber from cherry trees unusable.4

The first consideration for Black Knot disease management is selecting a variety of tree that is less susceptible or resistant to Black Knot. Several resistant varieties are commercially available. Next, try to remove any nearby wild trees that are infected. A. morbosa ascospores don’t travel long distances, so selecting a site with few nearby wild trees will greatly reduce infection. To manage the disease in an established orchard, the most important tool is pruning away infected branches. This is most effective in the winter, when spores are inactive and branches are easier to see. Look for any swellings on the branches and cut off those branches 15-20cm below the branch. Burn, bury, or remove the infected material to ensure it doesn’t release spores in the spring. In commercial orchards, pruning can be coupled with spraying fungicide in the spring to kill any ascospores from outside sources or from galls that you missed. Spraying in the spring protects the young branches from infection until they can develop thicker bark.6,8

Currently, the disease is restricted to North America. In order to prevent the spread of the disease, other countries with plum or cherry industries have adopted strict quarantine and sanitization requirements. So far, this has successfully prevented A. morbosa from leaving North America.4

Similar Species

There are numerous species of fungi, bacteria, insects, and other organisms that cause malformations on trees. None of these look as distinctive as A. morbosa galls. On twigs and branches, A. morbosa is the only species that forms galls that resemble dried cat poop on a stick. Most similar galls are roughly spherical instead. On trunks, A. morbosa looks very similar to a burl, which can have a variety of causes. However, most burls have a diameter that is less than the diameter of their host tree while swellings from Black Knot are often larger than the diameter of the host tree. A. morbosa is also the only species to make locules on the surface of the swellings, which greatly simplifies identification. Additionally, identifying the host tree simplifies ID – if your tree isn’t a species of Prunus, the infection is caused by a different species.

People are most likely to confuse Black Knot with Chaga (Inonotus obliquus, FFF#136), especially when looking at large galls on the trunk. This happens so frequently I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve had to say, “No, that’s not Chaga, it’s Black Knot.” There are two easy ways to tell the difference between the two species. First, look closely: the surface of an A. morbosa gall is studded with circular bumps (each bump represents the tip of one locule). Chaga does not produce any spores, so its surface lacks locules or any other spore-bearing structures. Second, consider the type of tree the gall is on. Black Knot grows on Black Cherry as well as other cherries, plums, peaches, and dates. Chaga is usually found on birch, but may also appear on beech, maple, alder, ash, oak, and elm.9 Since the host ranges do not overlap, you can tell the difference between the two species by identifying the host tree. Additionally, you can consider the texture of the gall: Chaga has a brittle exterior that easily breaks apart into small cubes, while Black Knot is woody throughout.

To help you distinguish Chaga and Black Knot, here are some tips for Black Cherry identification. A mature Black Cherry can be recognized by its distinctive bark that looks like it’s covered in burnt potato chips. Younger trees are a little harder to identify (unless you find swellings that look like dried cat poop on a stick), so you have to check other features. Black Cherry leaves are simple, alternate, roughly oval in shape, and have pointed tips. The top of the leaf is dark green, smooth, and shiny. The underside of the leaf is lighter and may have some hairs along the central vein. The edge of the leaf is finely serrated. In the spring, trees produce cylindrical clusters of small white flowers. Each flower gives rise to a small purplish fruit. These fruits can look quite messy when they fall off the tree.10

Edibility

A. morbosa is poisonous, since its host trees are poisonous.11,12 Normally, this wouldn’t be a problem – who would intentionally eat something that has the texture of wood and looks like cat poop? However, poisoning is a problem if you confuse it with Chaga. Chaga is typically ground up and made into tea for its medicinal properties. Since A. morbosa is poisonous, drinking a Black Knot tea would have the opposite effect.

Black Cherry is also poisonous (in fact, it is the most toxic species of Prunus), so don’t eat any parts of the plant. The bark, stems, leaves, and seeds all contain cyanide and ingestion is potentially fatal.11,12

Taxonomy

Black Knot is placed in the class Dothideomycetes, which does not contain many familiar fungi. Two fungi in this group you might have heard of are Apple Scab Disease (Venturia inequalis) and Scorias spongiosa (FFF#116). The distinguishing characteristic of Dothideomycetes is that their asci have two layers and are contained in locules. In mycologese, two-layered asci are called “bitunicate asci.”7 The outer layer is attached to the base of the ascus and provides support. The inner layer can slide back and forth. This ability allows the ascus to elongate by sliding the inner layer outward. Ascus elongation is an important part of spore release because the ascus sits at the bottom of the locule but must grow up to the tip of the locule in order to release its spores (otherwise, the spores would get stuck inside the locule).

| Kingdom | Fungi |

| Subkingdom | Dikarya |

| Division (Phylum) | Ascomycota |

| Subdivision (Subphylum) | Pezizomycotina |

| Class | Dothideomycetes |

| Subclass | Pleosporomycetidae |

| Order | Pleosporales |

| Family | Venturiaceae |

| Genus | Apiosporina |

| Species | Apiosporina morbosa (Schwein.) Arx13 |

See Further:

http://plantclinic.cornell.edu/factsheets/blackknot.pdf

https://www.messiah.edu/Oakes/fungi_on_wood/crust%20and%20parchment/species%20pages/Apiosporina%20morbosa.htm

https://web.extension.illinois.edu/hortanswers/detailProblem.cfm?PathogenID=86

https://www.minnesotawildflowers.info/tree/black-cherry

*https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mBcTXBhYzfM

Citations

- Kuo, M. Apiosporina morbosa: Black Knot. MushroomExpert.Com https://www.mushroomexpert.com/apiosporina_morbosa.html (2004).

- Koetter, R. & Grabowski, M. Black knot. University of Minnesota Extension https://extension.umn.edu/plant-diseases/black-knot (2018).

- The Larch. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mBcTXBhYzfM (2017).

- EFSA Panel on Plant Health (PLH) et al. Pest categorisation of Apiosporina morbosa. EFSA Journal 16, e05244 https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5244 (2018).

- Emberger, G. Apiosporina morbosa. Fungi Growing on Wood https://www.messiah.edu/Oakes/fungi_on_wood/crust%20and%20parchment/species%20pages/Apiosporina%20morbosa.htm.

- Black Knot: Apiosporina morbosa. http://plantclinic.cornell.edu/factsheets/blackknot.pdf (2018).

- Beug, M. W., Bessette, A. & Bessette, A. R. Ascomycete fungi of North America: a mushroom reference guide. (2014).

- Black Knot (Apiosporina morbosa [syn. Dibotryon morbosum]). University of Illinois Extension Hort Answers https://web.extension.illinois.edu/hortanswers/detailProblem.cfm?PathogenID=86.

- Lee, M.-W. et al. Introduction to Distribution and Ecology of Sterile Conks of Inonotus obliquus. Mycobiology 36, 199–202 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23997626/ (2008).

- Prunus serotina (Black Cherry). Minnesota Wildflowers https://www.minnesotawildflowers.info/tree/black-cherry.

- Toxic Plant Profile: Prunus Species. University of Maryland Extension https://extension.umd.edu/learn/toxic-plant-profile-prunus-species.

- Prunus serotina. NC State Extension https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/prunus-serotina/.

- Apiosporina morbosa. Mycobank http://www.mycobank.org/name/Apiosporina%20morbosa&Lang=Eng.

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

1 Response

[…] Note: this is an archived post. You can view the current version of this post here. […]