#014: Characteristics of Phylum Chytridiomycota

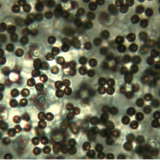

Phylum chytridiomycota is the oldest phylum of fungi, with a fossil record dating back to the Vendian period (around 500 million years ago). It is no surprise, then, that chytrids are the simplest fungi. Hyphae produced by chytrids can be unicellular, diminutive rhizoids or multicellular and as large as those produced by species in the other fungal phyla. Chytrids are unique among the fungi in that they produce motile spores. Each spore is equipped with one whiplash flagellum at its posterior. Other fungus-like organisms which produce motile spores (often with multiple flagella) but have cellulose cell walls are no longer classified as fungi (chytrids, like all other fungi, have chitin in their cell walls). Asexual zoospores are formed in a zoosporangium and are released through a pore. The simplest chytrids form a very small network of rhizoids and produce only one zoosporangium per thallus. However, more complex chytrids may form two or more zoosporangia per thallus. When the zoospores are released they swim around to find more material to colonize. Sexual reproduction varies among chytrid species. Male and female gametes are produced and one or both of these may be motile. The gametes are attracted to each other by secreted pheromones. A male and a female gamete will then fuse together and produce a zygote, which becomes thick-walled and can survive adverse conditions.

It is not surprising that chytrids primarily live in aquatic habitats, considering that their spores need water in order to swim. Chytrids can be found in freshwater, salt water, soil (that periodically becomes wet during rain), and even in animals’ guts. Most chytrids are either saprophytic or parasitic, although a few are mutualistic. Many fill an important ecological role by degrading complex molecules like chitin, cellulose, and keratin. Next spring, if you were to examine some pollen found floating on the surface of a pond, you would surely find the pollen well-colonized by chytrids. The rapid colonization of pollen is achieved by asexual reproduction. Once the pollen season ends, the chytrids switch to sexual reproduction to survive the rest of the year without a food supply. Chytrids can be parasitic on a number of different species, from algae and microscopic worms to large plants and amphibians. You may have heard about chytridiomycosis (FFF#157), which is killing millions of frogs worldwide. This disease is caused by the chytrid Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. A small number of chytrids form mutualisms with animals by helping to break down material in the animals’ guts. These are best-known in ruminants (animals like cows), which rely on a wide variety of microbes to break down the plant material they eat.

See Further:

http://website.nbm-mnb.ca/mycologywebpages/NaturalHistoryOfFungi/Chytridiomycota.html

![#011: Characteristics of Kingdom Fungi [Archived]](https://www.fungusfactfriday.com/wp-content/themes/hueman/assets/front/img/thumb-small-empty.png)

1 Response

[…] by growing into them or by being moved there by external forces. Some fungi, such as the chytrids (FFF#014) do have a short motile spore stage, but these spores are not the feeding part of the fungus. […]